FREE Handout Download

Overcoming Barriers to Communication

As a counsellor or psychotherapist, effective communication is your most vital tool. Yet, despite best efforts, barriers – often invisible – can inhibit this essential process. These barriers can emerge from language, culture, environment, the therapeutic relationship itself, or even the counsellor’s internal processes. Left unaddressed, they obstruct empathy, hinder rapport-building, and may limit client progress. This post explores the multifaceted nature of communication barriers and how to navigate them thoughtfully and professionally in practice.

Overcoming Barriers to Communication

After reading this post, you’ll be able to:

Ken Kelly: I think I first heard about this topic, Rory, really early in my counselling training. It’s called Barriers to Communication. I remember revisiting it again and again. What is interesting is, it follows you throughout the whole arc of your counselling career. Because barriers to communications are very real and sometimes unseen, and they can significantly affect how the relationship works out, and how well we are able to serve our clients. Tell us about these barriers to communication, what are they?

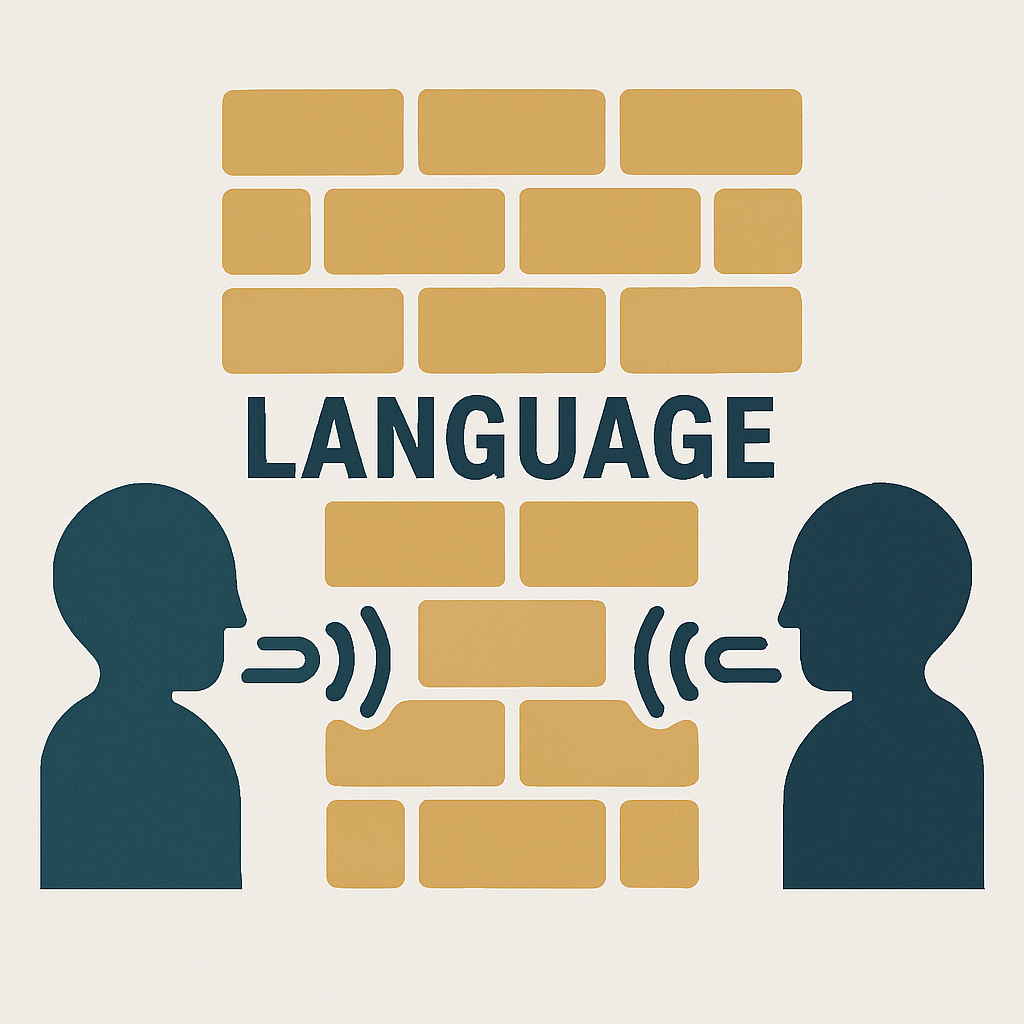

Rory Lees-Oakes: It’s an interesting one, and I think the first barrier that most people would think about is language.

When I was working with Mind, I came into my practice one day and there was a number of people sat in the reception who turned out to be immigrants from a place in Africa that’s predominantly French speaking. And they’re all speaking French, and the receptionist was scratching her head, and eventually they managed to find an interpreter and find out what was going on.

So I think the first thing is language. And language is very nuanced because we may think of it as in international language, French, German. But if you think about it, if you speak with someone who’s an American, they have a different kind of way of communicating. For instance, who would know that a faucet in America in some areas, is a tap, or a trunk is the boot of a car.

As famously said, two nations divided by a common language, we have to be very precise in understanding people’s language. So, that can be a barrier, as can someone having a regional accent.

And then we go on into the more kind of nuanced areas where we may be working with a neurodivergent client, we get into the area of what’s sometimes referred to as double empathy, where their way of communicating may be different to the way that we normally communicate with the people around us. Those are just a few.

And then we can move that into a wider sphere. How about communicating by email. Maybe you say to a client, can you email me? Maybe they haven’t got access to a computer, maybe they haven’t got access to a phone. There is lots of areas where we take communication for granted and we have to be very thoughtful.

Rightly, the beginning working with anybody is how they communicate and what they can communicate with. Because if we can’t get that piece right, we may not be able to form a relationship.

Ken Kelly: Yep, and there it is, bingo. Let’s take what counselling is, it is a communication process, but it is a communication process where we’re looking as the counsellor to create an environment where the person feels safe and free to bring who they really are.

Because if they’re holding part of themselves back for some reason, then it’s unlikely that they’ll get the true benefit from the sessions. And similarly, if the client doesn’t feel that they’re being heard, recognised, understood for who they are, then there may be a reluctance to show or bring their whole self.

Because we’re trying to create that non-judgemental environment. And I guess that’s why we need to have understanding of cultural presentations when we’re talking about barriers to communication, it can certainly be a barrier. And one of the things that is interesting to me is that there are hidden barriers.

So we’ve spoken about language, spoken about dialect that may be difficult to understand that person. I’ve spoken about maybe somebody that has a cultural difference, you’ve spoken about neurodivergence, Rory, and all of these maybe we would see in neurodivergence, I guess the training would need to be there to be able to identify what that looks like, we can then make the adjustments.

But unseen are things like, does that person feel that they can be overheard from the room that you are in? So, if you’ve got a counselling room and you sat there with your client and you can hear somebody in a room next door washing a cup, how does that client feel?

Does that client then feel safe, secure, and that confidentiality is being held? Will they bring their whole self or is that a barrier to communication? And similarly, can anybody see in the room? Has the room got a window? Has it got a little peep hole on the door or something that somebody might walk past. So those may be unseen.

Barriers to communication can also be outside noises. It can be the people digging up the road and doing the works to change the pipes, and they’ve got those big jackhammers going on.

And then, and I think this is an important one, Rory, the barrier to communication can also be us as the counsellor.

Rory Lees-Oakes: It’s very true, Ken. And as a male counsellor, I have, on more than one occasion, very gently said to a female client, I wonder how it is working with a male therapist.

And it was quite interesting, sometimes people say it’s fine, other times there was, you could always tell it in the pause, there was a pause before answering, and it was very difficult. And in one occasion, myself and the client both agreed that she’d probably be best off working with a female therapist. Her experience of men hadn’t been the best and she found that even though initially when we started it, she thought she was gonna be fine, as we progressed, it became clear, at least to me, and I think it was obviously clear to her that the relationship wasn’t building. And that question that I asked was the catalyst for her to say, I think I wanna see a female therapist.

And that was absolutely fine. Absolutely fine. A referral was made and we wished her well, and I think one of the things about it was that as she was leaving the practice room, she was really apologising. It’s not you, it’s nothing to do with you, you are lovely. And she went off to find a female therapist.

And I think that, that might not be unusual. And even in some cases, there could be a racial element. Someone from the black or Asian community, or the queer community as it’s now referred to, may find themselves better served in themselves by working with someone from that community.

And we have to be very thoughtful with that, as we do with the way we communicate. There’s no room for sarcasm or judgemental behaviour in the therapy room because again, that can form a barrier to communication. We are working with the clients and part of us is engaged in that helicopter activity, hovering over the two of us, like you would if you were in a helicopter, observing what’s going on. Occasionally I’ve asked the question and we’ve had a long conversation around it and acknowledge that I’m a man and, it might be that I look like someone of that client’s past and working through that transference and renegotiating it.

So occasionally I’ve said, I’m not that person. I may look like that person, but I’m not. I fully understand where you’re coming from. And that was very helpful for the client because she could then reset herself into seeing me as a new person. Reworking the transference, that history, and seeing me as new, and not from someone from her past.

So we have to be very careful. But that I think is one of the biggest issues in therapy that limits and can block communication, transference, and preference for therapists to be honest.

Ken Kelly: Hundred percent. And it’s interesting you were speaking there, Rory, and saying helicoptering over the relationship. And eventually as a mature therapist, you get to that point that Rory’s explaining, you are always watching out for this, because anything that becomes a lens between the communication which distorts what’s being said, or how that is being perceived, or causes the client to maybe hold something back, or causes the counsellor to not be able to go there or hold something back, is a barrier. It stops that free communication that is so necessary to the counselling process.

And it leads me into, we as the counsellor can be the barrier, and you’ve mentioned a little bit about that, but there may be unseen parts of us as the counsellor that become the barrier in the conversation, you mentioned transference, Rory, where suddenly without us really knowing, subconsciously, we’re no longer responding to the client in front of us. We, the counsellor, may be caught up in some transference and not be fully present. One of the questions or one of the exercises we did during my training are, what are the topics or presentations that you may not be able to work with, that you don’t feel comfortable to work with? Maybe because of your past, and the journey that you’ve traveled, or a family member, or something like that. And to really explore those and understand them so that they don’t become those barriers.

As Rory you coined a phrase, and I dunno if it’s yours, but it’s beautiful, the client can only go as far as the counsellor is able to go. If we are not able to go there, the client can’t go there. Therefore, it’s a barrier. If they bring something and that for us, causes a jolt with inside us. Yes, of course, there’s a whole lot of stuff that plays out, we gotta go to supervision and all that kind of stuff. But within that moment. We may steer away from that topic and go to something they may have said earlier or not want to delve into that. And that is a barrier in that communication, Rory.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, absolutely. As is a form of parallel process. Parallel process is where you are working with a client and they’re talking about issues that you are going through. So say for instance, you’re working with a client and they’re talking about a divorce and you are in the process, or have recently been divorced or separated from your partner, may very well be that the feelings that you are feeling, and the responses that are generated from those feelings, are not actually generated from the client’s frame of reference. It’s generated from your frame of reference. And that could get mightily confusing because you don’t know where the client begins and you end. So again, that is one for personal reflection, for supervision, and certainly as a former tutor.

I’ve observed skill sessions where someone was listening very intently to someone speaking about an issue they’ve had, and then all of a sudden they respond not from the client’s frame of reference, but from the role they start talking about their own experience. And you have to intervene as a tutor and say, okay, let’s pause there and just think about whose experience are you talking about, are you reflecting the clients or yours? And it’s usually a bit of a light bulb moment for students. They go, ah actually, it was mine. I’m talking about myself aren’t I? I’m like, yep, maybe you are. And that’s really important, and it happens a lot.

We all go through an arc of life with successes and difficulties. And occasionally we meet clients who are on the same trajectory, and quite frankly, we sometimes meet ourselves in the therapy room. We meet people who are going through the same difficult situations that we are.

Ken Kelly: Yes, so it’s an interesting topic, which starts out seeming maybe shallow and at a beginner level in counselling, what are the barriers to communication? They’re deep indeed.

And I’d like to end this by speaking about a barrier to communication. It’s a barrier to communication that maybe wasn’t as pre prevalent when I studied and graduated, and I certainly wouldn’t have covered this as a barrier to communication in my assignments, Rory, and that is technology. Technology can be a barrier. More and more there is a blended delivery from counsellors where you may be seeing that person face to face, in person in the room but similarly, you may be seeing that person via a video application, you might be speaking to them over phone, and you mentioned email earlier, Rory.

How is it for that person to engage in that technology? Are they proficient in it? Are we assuming that they use it as freely as we do. When you’re proficient with the technology, it becomes invisible and you don’t even see it, and it’s just, you click the button and you’re there and you engage.

But, perhaps for the client, if they’re not okay with that, they may not feel comfortable with that. And if they’re worrying, am I clicking the right buttons? Am I doing this right? Maybe having some frustration clicks before they actually meet with you. Is that not a barrier? Is that not changing where they’re at as they come in? And then when you’re working online, the internet can go down. That’s a barrier to communication.

Ken Kelly: It’s not something that we would ever have considered when we were training. Certainly when I trained, back in the day, people didn’t even have mobile phones or the internet.

Rory Lees-Oakes: I sound ancient, don’t I? But I sound very creaky and ancient, no mobile phones. But that was the truth.

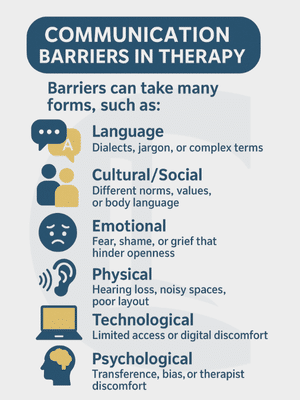

Communication barriers in therapeutic work can arise in many forms.

Common categories include:

This post explores each of these barriers in context and offers practical guidance to overcome them in your therapeutic work.

Language is often the first barrier to emerge, particularly in multicultural or cross-regional contexts. Communication complications arise not only through differing national languages but also via regional dialects, cultural idioms, or generational slang. Even simple differences in word usage, such as “faucet” versus “tap”, can create confusion – particularly for clients with limited language proficiency.

In addition, cultural interpretations of behaviour can vary widely. Eye contact, for instance, may be seen as a sign of honesty in some cultures and as confrontational or disrespectful in others. Communication differences may also arise with neurodivergent clients, whose social signalling and verbal expression do not conform to neurotypical expectations. Without an appreciation of these variations, misattunement can easily occur.

Begin each therapeutic relationship by understanding how your client communicates – what language, medium, and style they are most comfortable with – and be prepared to adapt accordingly.

In both casual and clinical conversations, jargon – be it professional shorthand or generational slang – can unintentionally become a barrier. While acronyms and clinical terms may be second nature to professionals, clients may find them confusing or alienating. A term like “FOMO” (Fear Of Missing Out) may resonate with younger clients but be meaningless to others.

Speak plainly. Ensure your language is accessible and always check for understanding. Simplify complex ideas without diminishing their meaning.

Communication is not confined to words alone. Environmental distractions such as background noise, temperature, or visibility into the therapy space can inhibit clients from feeling safe enough to disclose openly. For example, if a client can hear noises from adjoining rooms or feels they may be seen through a window or door, their sense of privacy may be compromised.

Ensure the counselling space is confidential, calm, and distraction-free. Consider how soundproofing, furniture placement, or visual privacy may influence your client’s experience of safety and openness.

Today’s digital landscape introduces a new dimension of communication barriers. While email, video conferencing, and text-based communication offer flexibility, clients unfamiliar with or anxious about technology may find it disorienting or stress-inducing. When a client is preoccupied with whether they’re using the platform correctly or if connectivity is unstable, the therapeutic process can be disrupted.

Always assess your client’s comfort with digital tools. Provide guidance where needed and consider alternative methods for those who struggle with technology.

Overcoming Barriers to Communication

The most sobering insight is that the counsellor themselves can become the very barrier they aim to dismantle. Factors such as gender, race, or perceived identity may unintentionally influence the therapeutic relationship. Some clients may feel more at ease working with a therapist who shares or understands elements of their cultural or personal identity.

Moreover, unconscious processes such as transference, countertransference, and emotional entanglement – especially when a client’s story echoes the therapist’s own life – can distort communication. In such cases, the therapist may unknowingly withdraw, redirect, or misinterpret the client’s experience.

Parallel process is another significant concern. This occurs when the therapist begins responding from their frame of reference rather than the client’s, often due to emotional identification with the content. This confusion can derail the therapeutic process, leading to a blurred boundary between the client’s experience and the therapist’s internal world.

Engage in regular supervision and self-reflection. Identify topics or client presentations that may trigger unresolved issues or unconscious bias. Strive to remain present, curious, and client-centred, especially when discomfort arises.

An often subtle but profound barrier arises when assumptions are made based on a client’s appearance, sexuality, ethnicity, or social class. When counsellors unconsciously attribute challenges to these characteristics, it can erode trust and reinforce stigma.

Practice cultural humility and remain aware of your assumptions. Approach each client with openness, allowing their experience to define the narrative, not your preconceptions.

Clients may be reluctant to disclose deeply personal matters due to emotional barriers such as shame, grief, or trauma. Likewise, counsellors may find themselves hesitant to explore specific subjects due to personal discomfort, inexperience, or social taboos, particularly around issues such as bereavement or sexual intimacy.

Cultivate emotional literacy and resilience. Create a non-judgmental, accepting space that invites full expression from the client. Your ability to hold complex emotional content can make the difference between silence and transformation.

A significant yet often overlooked barrier is the counsellor’s listening style. If the therapist interrupts, responds with personal anecdotes, or delivers advice too quickly, the client may feel misunderstood or dismissed. Effective communication requires both verbal and non-verbal empathy.

Refine your active listening skills. Use tone, body language, and verbal reflection to demonstrate understanding. Avoid shifting the conversation toward your own experiences or interpretations unless therapeutically appropriate.

Language differences, cultural misunderstandings, emotional inhibition, and environmental distractions are among the most common obstacles in therapeutic settings.

By adapting their language, creating a safe environment, reflecting on their own internal biases, and using supervision to process emotional responses that may disrupt communication.

Active listening builds trust and helps clients feel understood. It is key to navigating both verbal and non-verbal obstacles in the therapeutic relationship.

Overcoming Barriers to Communication

Communication barriers are not solely a novice concern; they persist and evolve throughout the career of every practitioner. Awareness of these barriers, and the commitment to reflect, adapt, and engage with humility, forms the bedrock of effective therapeutic relationships. By proactively addressing both the seen and unseen obstacles in your practice, you create a space where clients can bring their whole selves and begin the work of healing.

Patterson, T. (2022). Neurodiversity in the Therapy Room: Beyond the Double Empathy Problem.

Mearns, D., & Thorne, B. (2007). Person-Centred Counselling in Action. Sage Publications.

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us