Your FREE Handout

The CBT Model of Emotional Disorders and Mental Health Conditions

Feltham and Dryden (1993: 148) define psychopathology as ‘the science of mental disorder’, adding that ‘counsellors are more likely to speak of clients’ real problem/s or underlying problem/s than of psychopathology‘ (particularly perhaps as counsellors are not qualified to diagnose mental-health conditions).

The term ‘psychopathology’ forms part of the medical model, with which the modality of CBT – supported by its widespread practice in the NHS and manualised nature – is comfortable.

The CBT Model of Emotional Disorders and Mental Health Conditions

Indeed, CBT manuals and research studies often focus on clients with particular diagnoses.

CBT views mental disorder as resulting from negative core beliefs and assumptions, leading to negative automatic thoughts; these in turn impact on emotions and then behaviours.

These elements may become mutually reinforcing, for example social anxiety may lead to avoiding social situations, and this lack of exposure to socialising may then increase fear – and therefore avoidance – of this.

Psychopharmacology (i.e. the study of medication to address mental-health conditions) again sits well within the psychopathological model, given its shared basis in Western science.

Drummond (2014: 232) observes that ‘the majority of patients who are treated by CBT in a psychiatric hospital and a significant minority treated by CBT in general practice will be on at least one psychopharmacological agent’.

Indeed, books have been written that focus specifically on providing therapy to clients who are on prescribed drugs (e.g. Hammersley, 1995).

There are two classification systems internationally for mental-health conditions:

Each presents slightly different ways to categorise diseases, but only DSM-5 includes criteria and definitions to enable suitably qualified clinicians (usually psychiatrists) to diagnose disorders.

For example, DSM-5 (2013: xv111-ix) sorts anxiety disorders into ten categories, ordered by typical age of onset:

For each category, diagnostic criteria are given.

Whether a client self-refers or is referred by another practitioner to a CBT therapist, they may come with a mental-health diagnosis. It is therefore important to have a reasonable knowledge and understanding of such conditions.

While a referral from another professional may come with a written record of the client’s diagnosis (e.g. through a referral letter from a doctor), a self-referring client may use terms from psychopathology themselves without formal medical diagnosis.

In this case, it is important to realise that this could be a self-diagnosis (and so not necessarily be accurate) – based, for example, on what the person has seen on TV or read on the internet.

Many psychopathological terms have become commonplace in lay language used loosely (e.g. someone who is feeling a little sad claiming, ‘I’m so depressed’; someone who is naturally nervous about an important exam saying, ‘I have severe anxiety’; or someone referring to a detail-conscious colleague as being ‘so OCD’).

It is also vital from an ethical point of view for counsellors to be clear with clients that we cannot diagnose, one of our commitments to clients being to ‘work to professional standards by … working within our competence’ (BACP, 2018: 6).

The questionnaires used in the CBT assessment relate to the psychopathological model, with depression being measured by PHQ-9 and/or Beck’s Depression Inventory, anxiety by GAD-7 (or HADS – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – for hospital inpatients), stress by PSS-4, and suicidality by BSSI.

These assessments are important to ethical and professional working in order to scale risk, so informing the therapist’s decision on what course of action is most appropriate to the individual client’s situation.

The questionnaire scores also provide a baseline position. This allows comparison in review sessions and at the end of therapy, which can be helpful for the client (e.g. in understanding their own emotional wellbeing, which is empowering), the therapist (e.g. in researching effectiveness) and the organisation (e.g. in securing funding).

Last but not least, the absolute and relative scores in GAD-7 and PHQ-9 give the therapist an early snapshot of whether anxiety and/or depression are present, and the balance between them; this can help in planning initial treatment.

While DSM-5 does not include suggested treatments, other organisations and individuals have done so – for example, in the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) via clinical guidelines, which provide evidence-based recommendations on treatment protocols.

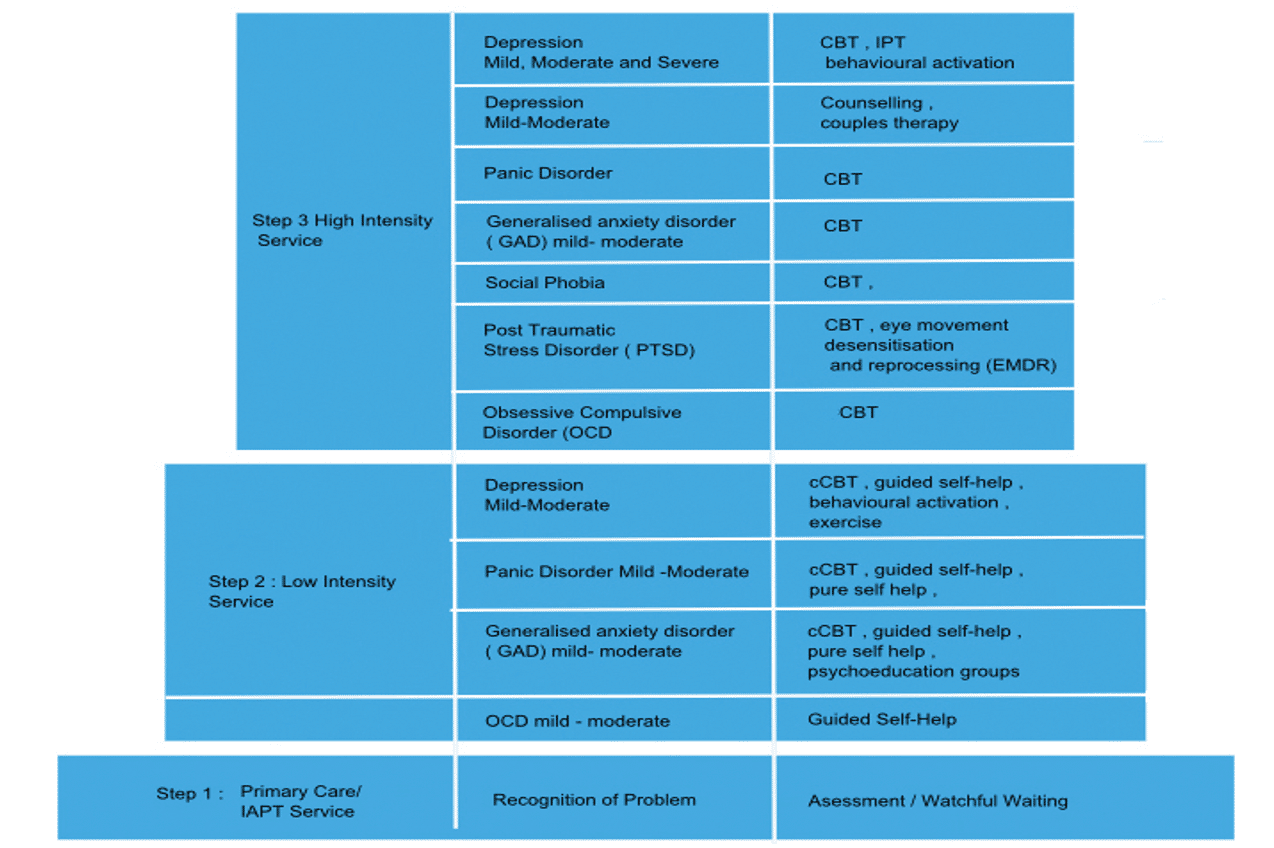

In its clinical guidelines, NICE advocates using the IAPT stepped approach (as shown in the diagram below).

The IAPT stepped-care model

[Source: https://www.uea.ac.uk/medicine/departments/psychological-sciences/cognitive-behavioural-therapy-training/-about-iapt-and-the-history-of-the-programme/stepped-care-model-information]

Apart from helping the CBT therapist identify possible risk and so ensure clinical safety, the assessment questionnaire scores also inform their decision on whether CBT is an appropriate therapy for the client, and whether they have the competence to work with the client and their presenting issue(s) to an appropriate professional standard.

For example, a very high score on one of the questionnaires may necessitate onward referral to a practitioner or service better placed to help the client.

If we again use anxiety as an example, NICE guidelines (2011: 19) recommend that therapists:

‘consider referral to step 4 if the person with GAD has severe anxiety with marked functional impairment in conjunction with: a risk of self-harm or suicide or significant comorbidity, such as substance misuse, personality disorder or complex physical health problems or self-neglect or an inadequate response to step 3 interventions’.

CBT Model of Emotional Disorders and Mental Health Conditions

It is also important – if a client presenting for CBT is initially assessed as having a high score in one area – to bear in mind that they might have another mental-health condition that includes this but is more complex.

For example, a person with high anxiety may in fact have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In this case, the CBT therapist may need to refer them on if treating this disorder fell outside their professional competence (e.g. the two therapies recommended by NICE (2018) for the treatment of PTSD being trauma-focused CBT or EMDR).

In both receiving and making referrals as a counsellor, it makes sense – whatever our personal view of psychopathology and the medical model – to accept ‘a psychopathology that can act as an intermediary … a go-between … a language for the meeting place between approaches’ (Sanders et al. 2009: 151).

This is especially important when working as part of a multidisciplinary mental-health team, for example in the NHS.

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fifth Edition (DSM-5), American Psychiatric Association

BACP (2018) Ethical Framework for the Counselling Professions, BACP: https://www.bacp.co.uk/media/3103/bacp-ethical-framework-for-the-counselling-professions-2018.pdf

Drummond L (2014) CBT for Adults: A Practical Guide for Clinicians, Royal College of Psychiatrists

Feltham C & Dryden W (1993) Dictionary of Counselling, Whurr Publishers

Hammersley D (1995) Counselling People on Prescribed Drugs, Sage

NICE (2011) Common Mental Health Problems: Identification and Pathways to Care (clinical guideline), NICE

NICE (2018) Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (clinical guideline), NICE

Sanders P, Frankland A & Wilkins P (2009) Next Steps in Counselling Practice: A students’ companion for degrees, HE diplomas and vocational courses, PCCS Books

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us