Autism-Informed Practice Course

Gain the Knowledge & Skills to Support Autistic Clients with Confidence & Compassion

The following article is taken from our Autism-Informed Practice course.

Gain the Knowledge & Skills to Support Autistic Clients with Confidence & Compassion

In contemporary counselling practice, the importance of preparing a therapeutic environment that respects neurodivergent needs—especially those of autistic clients—cannot be overstated. Understanding and accommodating the sensory and comfort-related preferences of autistic individuals can transform the counselling experience.

This article summarises the key elements of preparing an autism-friendly space and offers actionable recommendations for counsellors seeking to make their practice more inclusive and responsive.

Preparing the Therapeutic Environment

By implementing the guidance in this article, you will be able to:

Ken Kelly: Preparing the counselling environment for autism friendly care. What do we mean by that, Rory?

Rory Lees-Oakes: I think that’s a very good question. And I’m going to start off by saying that as therapists, we really have to have three guiding lights when it comes to thinking about the care and service to our clients, and that is inclusivity, and accessibility. Are we making sure that our environment and our offer is both inclusive, and allows clients to access our service?

How are we going to best make a therapeutic alliance? Because the research is clear that it’s quality of the relationship that shows the best outcomes in therapy, and also that we have an ethical, and professional responsibility to make sure that we’re inclusive. So when we take those three ideas, and put them across a therapeutic environment for people who are neurodivergent or autistic, what we need to think about is how we can make reasonable adjustments and respect the autonomy of the client? How can we make sure that client is treated as an individual with their own view of the world? We do that by making reasonable adjustments.

I recently interviewed someone who’s autistic and I just wrote back, ‘Is there any adjustments I can make for you?’ We’re meeting on zoom. And she wrote back and said, ‘Thank you very much!’ Because someone had thought about the fact that she might have needed some reasonable adjustments.

We’re keeping these ideas in mind so that we can say to a client, ‘Thank you for sharing that you’re autistic, is there anything I could do for you? Is there any adjustments I could put in place? What would make the environment more comfortable?’

And therapy shouldn’t always be comfortable. But what can we put in place to help you.

Ken Kelly: I like it, I like how your starting position was in the very first email. Before meeting with the person, you were exploring what that looked like.

And I like how you said level the playing field.

We had a little device back when we lived in South Africa, and it was a little speaker. And apparently, this speaker emitted a pitch that chased away mosquitoes.

Our daughter could hear the buzzing of the box, and she didn’t like it. For her, it was a very irritating and invasive sound. Both myself and my wife, we couldn’t hear a thing. And we turned it off for her.

That’s levelling the playing field. It’s being aware that we might not be able to see, hear, smell, feel ourselves, but other people can, and it’s being in their frame of reference.

So we are looking at that, and you’ve already spoken about respecting the autonomy of that client. They’re reaching out to us right from the very beginning. We’re exploring what would make them more comfortable, and being there ready to make those small adjustments. And what are some small adjustments that we might see or that we might look at first that are very common?

Maybe it’s something that you put in your counselling room because it makes it smell nice, and it makes it smell fresh. It might be adapting the lighting you have in your room, the lighting that you very specifically chose because it creates the right atmosphere.

All of that is through us wanting to do the best, but we go and re look at that through the lens of what we learn around neurodivergent individuals and what their needs may be. Sound management, that beautiful clock we have in the corner, might have a very loud clicking sound that puts somebody off.

Natural scents that we find very pleasant may be really overpowering to the point that it is distracting to a neurodivergent individual. We think we’ve got lovely lights, lovely smell in the room, and the room is nice and quiet. So it’s having those thoughts, learning, and I guess doing the CPD that is outside our own frame of reference.

Rory Lees-Oakes: I think the starting position if we want to be inclusive and have accessibility, is to have that in our initial reach out to clients.

So some people send an information pack out, and if that is in the information pack, do you have any environmental preferences? If you’re neurodivergent or autistic, please come back to me. Then you have a starting point. And it might be that some people don’t like aftershave. I mean i t’s not just people who are neurodivergent that might have difficulty with smells. It’s also people with trauma, the smells can be very triggering.

You cannot have an effective therapeutic alliance if someone’s uncomfortable. You just cannot do it, because they’re focusing on their discomfort rather than engaging in what’s going on. So there’s a few starting points.

Ken Kelly: Thank you, Rory. And they really resonate with me. I was diagnosed autistic and sound is a big thing for me.

So I struggle in a coffee shop, or a restaurant. I’m okay for a little while, but it’s wearing on me and eventually I need to leave. So I carry around noise cancelling headphones for myself. So I’m basically making the adjustments for self.

So that’s me with sound. Scents are a big trigger for me. If I go on a bus, or on a train, or walk through a crowded place and there’s a lot of different perfumes, it burns the top of my nasal passages where it physically hurts, and it usually puts me into a sneezing spree.

So to reach out for therapy with all the overwhelm you’re facing in your life and actually have somebody who sees you, who acknowledges that, from the very start of the relationship. Wow. Because I haven’t experienced that, when I went through my own training, Rory, and I had to do my own personal counselling.

And then I’ve had times post my training where I needed to dip back into my own therapy for things that had come up for me in my life. And I was not recognised or given those options. It’s nice to see that this is now coming to light. This information is being shared for the benefit of all.

It’s going to benefit the practitioner because we only want to serve and do our best, and it’s going to benefit the neurodivergent individual who can now have an environment that is more suited to their needs.This is such a really important topic, Rory. But I’m also mindful, that when we’re talking about sound, it might even be tone of voice or the communication style, that the therapist may use within the session. What can we learn about that?

Rory Lees-Oakes: I think that’s interesting.

And just to rewind a little bit, those who are working with young people, I think we have to acknowledge that young people’s hearing is better than older people’s, generally, there are exceptions. And they can hear things we can’t. If you’ve got a room, get a young person in and say, what can you hear?

And they may be able to pick up the things you can’t. So in terms of tone of voice and communication style, it’s important that we adapt verbal communication to align with clients preferences. It comes back to inclusivity and accessibility.

And some clients may appreciate a calm, monotonous tone which they find easy to process while others may want a more upbeat, expressive style. No one’s asking therapists to be voice actors or retrain their voice to work with clients, that’s not a reasonable adjustment.

But, just to think about how we speak to people. It might be, we just have to slow down a little bit. Clients would usually tell you in my experience, some might not, but some might. Which if I’m really honest, people who talk very slowly, I get quite anxious because I’m hanging on the next word. I start to finish the sentences off for them if people pause too long. Of course, what happens then is I’m not thinking about what’s going on for me,

I’m trying to help the person who’s speaking by finishing the sentences off. We need to think about tone of voice, but I also think about communication in general. It needs to be really clear. Using clean language. Things like metaphor and simile may be very difficult for autistic clients. Little things that we’d say all the time, we’re all in the same boat. A lot of people listening to this might say, Oh, we’re all in it together, aren’t we? That’s what that means. But actually, for an autistic person, they might think, where’s the boat?

So we have to be very clear in our communication.

Ken Kelly: Oh, yes. Very much and two areas I struggle with in communication is very soft voices where I find that I need to really strain to hear. I’m almost leaning in and maybe you can relate to a conversation you’ve had, in a noisy environment where someone was speaking too soft where you couldn’t fully understand everything they were saying.

How did that feel for you? Certainly for me, I feel I’m really straining to listen and to grab everything. But I still miss things and it’s difficult to respond then because you’re missing little pieces of that. The other side of the coin for me is when the voice is too loud, certain people just have a really loud voice and way of communicating, and for that, I feel I want to take a step back and be a little bit further away from that voice. And maybe you’ve experienced that listening to this as well.

You don’t need to be neurodivergent to have experienced these kind of things. It’s great speaking about all of this, but what are the practical things that you can do?

And these are practical tips for implementation and peer collaboration. And you can start off by auditing your practice environment, really having a look around your practice and with the knowledge you’ve gained. Mapping that against what you have in your therapeutic room and asking yourself questions.

Is the lighting too bright? Does the clock tick loudly? Are there any strong odours present within my room? Seeking feedback from supervisors, peers, and clients as well. You can ask your clients how they found your room, your environment, the communication methods, actually asking for that feedback.

And if you are considering reasonable adjustments, within my home, I have dimmer switches on my lights, so that depending on where I find myself, I can turn the lights down. You might consider getting fidget toys for somebody that maybe has ADH I’m going to leave the D out. I’m leaving the D out. Take the D out. They may wish to fidget with this. You might consider tax deductibility of those changes that you make within your room. Another thing is wall decoration.

There are certain wallpapers that for some reason make my eyes go funny. I find it very difficult to focus my attention.

So if I was in a therapy session, and the counsellor had behind them a really busy, distracting wallpaper design, I might find it really difficult to focus on that person because my eyes keep on getting pulled to the lines and patterns on the wallpaper. And that’s just me speaking of my experience, and I realise every single neurodivergent individual is their own person, and you would need to speak to them. Any thoughts and final remarks, Rory?

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, I think that it’s always trying to be that best fit for a client and meeting the client where they’re at.

And there’s no better way. Then having something like a 30 minute preliminary introduction session. Yes. Where people can come to your office. You have to have a universal approach to working with neurodiversity. So it should be on your listing on your website that you make reasonable adjustments, it should be when you’re sending information out for this 30 minute preliminary meeting.

Make reasonable adjustments and wait for any feedback, whether that is online, or face to face, there’s different things we can do. And obviously have an up to date picture of yourself, a nice picture that’s not been manipulated, as they used to say, warts and all, and meet the clients.

And it may be when you meet the client, the client says, yeah, I think this works. Or they might go away and think I just don’t like Rory’s voice. It’s a bit too loud, because I tend to be a bit loud, I’ll go and find someone else. And you know what? That’s fine. Because we can’t be everything for everybody, but we have to do as much as we can to make sure that we are offering an ethical service. Now, I’m gonna come back as we come out of this kind of topic to say that it needs to be inclusive and have accessibility. It needs to be ethical and professional responsibility on our part to provide those reasonable adjustments. And unless we do that, we will not get an effective therapeutic alliance where the therapy takes place and the magic happens.

A cornerstone of ethical counselling practice is respecting client autonomy, a principle highlighted across professional codes of practice. For autistic clients, this means actively involving them in the environment-setting process. When clients disclose their autism, it is courteous and practical to ask if specific adjustments would make them more comfortable. The term to remember is reasonable adjustments—changes that enhance the therapeutic environment without being impractical.

The concept of ‘reasonable adjustments’ requires flexibility and creativity. For example, if a client finds the colour of a chair unsettling, instead of purchasing new furniture, simply covering it with a throw could be an effective solution. When preparing the therapeutic environment, practitioners should be mindful of balancing practicality with the client’s sensory needs to create an inclusive space without incurring unreasonable costs.

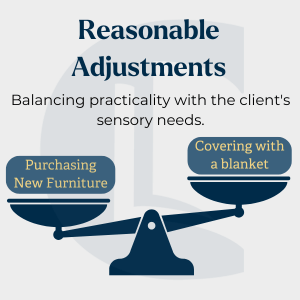

Autistic individuals often experience heightened sensitivities to sensory stimuli, including sound, light, and scent. These sensitivities can fluctuate with stress or relaxation levels, making maintaining a flexible and accommodating environment crucial.

1. Sound Management: Some autistic clients are highly sensitive to background noise. The clock ticking or distant sounds outside the room can be overwhelming. To minimise distractions, consider removing noisy items or using white noise machines to help mask external sounds.

2. Neutral Scents: Strong fragrances from personal products or room fresheners can disrupt an autistic person’s focus.Maintaining a scent-neutral space can prevent discomfort. Ask clients if specific scents could affect their concentration or comfort.

3. Adaptable Lighting: Bright lights can cause sensory overload. Autistic clients may shield their eyes with hats, sunglasses, or even hoodies during sessions. Offering options such as dimmable lights, closed blinds, or curtains provides a more adaptable setting that clients can control according to their comfort levels.

Creating a comfortable seating arrangement and offering sensory tools can significantly benefit engagement for autistic clients.

Adapting verbal communication to align with clients’ preferences can help create a more supportive environment. Some clients may appreciate a calm, monotonous tone, which they find easier to process, while others might prefer an upbeat, expressive style. Observing and adjusting each client’s reaction to different tones will help build rapport and enhance the therapeutic connection.

A 30-minute preliminary introductory session can be particularly valuable for autistic clients. It allows them to familiarise themselves with the therapist’s tone, pace, and environment. This session provides for any necessary adjustments to be identified early on, making future interactions smoother and more effective.

Building an autism-friendly space is an evolving process that benefits from peer insights and shared experiences. Here are some steps to facilitate this process:

Preparing the Therapeutic Environment for Autism-Friendly Care

Creating a therapeutic environment tailored to the sensory and comfort needs of autistic clients enhances the inclusivity and effectiveness of counselling practice. While these adjustments are particularly beneficial for autistic individuals, many neurotypical clients may also find a sensory-considerate environment beneficial. Integrating these changes will ensure a more welcoming and responsive practice, ultimately creating a setting where all clients feel respected and understood.

Nicholson, E. (2016). What works when counselling autistic clients? Healthcare Counselling and Psychotherapy Journal, October issue. Available at: BACP Healthcare Counselling and Psychotherapy Journal

Elaine Nicholson MBE’s website offers further resources for counselling neurodivergent individuals.

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us