Autism-Informed Practice Course

Gain the Knowledge & Skills to Support Autistic Clients with Confidence & Compassion

The following article was taken from our Autism-Informed Practice course.

Gain the Knowledge & Skills to Support Autistic Clients with Confidence & Compassion

In therapeutic practice, particularly with neurodivergent individuals, it is crucial to recognise the person beyond the diagnostic label. While diagnoses like autism spectrum disorder (ASD) offer insight into an individual’s experiences, they can also contribute to harmful stereotypes and misconceptions. This article explores the importance of seeing the individual, not the label, and offers therapeutic strategies for counsellors and psychotherapists to support neurodivergent clients effectively.

A nuanced understanding of neurodivergence emphasises the diversity within conditions like autism, challenging outdated ideas that categorise individuals by oversimplified labels such as “high” or “low” functioning. Counsellors must engage with clients as complex individuals, acknowledging their struggles and strengths.

Seeing the Individual Not the Label – Rethinking Neurodivergence

Ken Kelly: What is neurodivergence and seeing past the label or the definition, and recognising that behind this is a person.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Absolutely, Ken. People aren’t a series of labels where things are stuck on.

Therapists need to understand the human condition and how it might impact on an individual’s life. When people talk about neurodivergence, there is a habit, of people thinking it only applies to people who are autistic, or maybe people with ADHD. And the fact of the matter is, it’s an umbrella. It can be dyslexia, dyspraxia, Tourette’s syndrome, where people have maybe involuntary physical and vocal tics, and sensory processing differences.

So we need to think about that. What we also need to think about, is people can acquire neurodivergence. You might get people who’ve been in some form of accident, or have a brain tumour and they acquire it, and become neurodivergent by acquisition.

So although we try not to label clients, having an understanding of the language allows us to get closer to the client, and also be able to access their frame of reference. And that’s what being a therapist is about, accessing someone’s frame of reference and being able to see the world as they see it.

Ken Kelly: The term neurodivergence, coined by an Australian sociologist, Judy Singer, refers to individuals who experienced variations in brain function. So this is a quote or a direct lift from how Judy described this: leading to difference in sociability, learning, attention, and mood regulation.

As a neurodivergent man, diagnosed about seven years ago, I can definitely relate to a lot of those words. And neurodivergence is not a medical disorder, but a natural variation within the human population, it’s for that reason that I think you are right, Rory. The dropping of the D at the end of ADHD, with the D being disorder, ASD, Autism Spectrum Disorder.

I think that language is losing favour, and will be replaced. Let’s talk about some of the core characteristics of neurodivergence, because neurodivergence comes as a wide range of conditions, each affecting individuals differently.

And I think this is the main takeaway from what I’ve just said there, wide range of conditions affecting individuals differently. And what we don’t want to be doing as we dive into this topic is forming a picture or a label that we go, oh, that person is neurodivergent, therefore, they are likely to think like this, act like this, experience these challenges.

It is very varied amongst individuals. And I guess that’s why we say looking beyond the label and looking at the individual themselves. And of course, just a very brief overview autism spectrum, I’m not saying the D on there, individuals on the autism spectrum often experience differences in social interaction, communication, sensory processing, may have very specific interests. May have not will always have, and that’s really important here. One of the things that came up for me when I disclosed my autism diagnosis.

I shared with certain family members, and they said you can’t be and then they started listing a whole load of traits that they saw in me that did not fit their label of autism. So they said you can’t be because, X, Y and Z. So one of them was that I worked for some time as an entertainer.

So I was quite happy standing up in front of a group of 1000 people and entertaining them and holding them in the palm of my hand. And they said, you can’t be autistic because an autistic person is very shy and is not socially interacting with people, and of course, that was maybe true for some, but certainly not for myself.

And I know if we look to the media, there are many autistic individuals that are in the limelight, that are in the entertainment world, that are regularly speaking out on television to millions of people, at rock concerts to tens of thousands of people.

There is a whole spectrum where you might find yourself, and it may change from day to day. Dyslexia, that’s something I can certainly relate to from my earliest years. I remember I was probably about four. I remember we started getting basic words that we had to look at. And for me, they just looked like weird patterns.

And it was like everybody else, they were able to put these weird patterns in some kind of order that said the cat sat on the mat. Me, I was just looking at these patterns going, what is this? And this learning challenge impacts reading, writing, spelling, due to difference in how the brain processes that information. Dyspraxia, I relate to that as well, affects coordination, motor skills, leading to difficulties in movement and planning.

Tourette syndrome, involuntary physical or vocal tics, sensory processing, differences. Individuals may have heightened or reduced sensitivity to sensory inputs affecting their daily lives and functioning.

So there’s a very brief overview of what we might see when we refer to neurodivergence. There are literally millions of people that might either have a diagnosis or self identify to any of those areas that we’ve covered under neurodivergence, but yet every single one of those people are unique, is different, and they are on their own journey.

And that’s the importance, is that we see the individual, not the diagnosis, or not the neurodivergence first. Yet, we still are respectful of neurodivergence in the way that we work.

Rory Lees-Oakes: I think the challenge for therapists is to acknowledge that people are different in the way that their thinking and processing goes. But to see the person behind it, I think in some cases to acknowledge the difficulties it brings. We’re living in a kinder society where individual differences are seen as quite the norm and people are giving time and making adjustments for those individual differences.

But still, it can be a challenge. I can think of at least a couple of clients who have struggled with different parts of neurodivergence, because it wasn’t particularly them, it was the people around them, sometimes their family, who, say thoughtless things to them.

You’re a clumsy oaf, that’s no good to someone who’s dyspraxic, someone who has difficulty with coordination, you’ll knock the odd thing over. Calling someone a clumsy idiot, or you’re flipping like a bull in a China shop, isn’t helpful because it’s not something they can easily control.

So yeah I have worked, before the term was even in my awareness, with people who have struggled with the way their brains were wired up, to give it a good example. So just to have a therapist who understands that, and allows the space to talk about the challenge and what someone might want to do with it, I think is mightily helpful in therapy.

So we don’t have to give a label, but just give the space, listen, and understand that this is what it might be.

Ken Kelly: Yeah, it’s an interesting topic because we spoke about how it almost seems like it’s emerging at the moment, coming into its own, with more information being readily accessible. With the world being a much smaller place where we can speak on social media, and identify with others on their journey, and have instant access to other people. But one thing that is interesting is looking to the statistics.

There is an estimated 15 to 20 percent of the population that would fall into neurodivergence that we’re speaking about right now. If we look back historically, there was a time when women could not be diagnosed as neurodivergent. It just wasn’t, they just weren’t having it. It was a male only thing. Many neurodivergent individuals may be unaware of their neurodivergent status, they may have not seen that or recognise that.

And I think these are important considerations for us as counsellors and psychotherapists.

The evidence points to a high incidence of misdiagnosis with anxiety, depression, personality disorders. Having this information out, for us as counsellors knowing what to look for, what to be sensitive to, we can really aid somebody on their path, if it is done sensitively.

We’re not here to diagnose. Diagnosis is a very formal process, and it’s done by specialist individuals. We as counsellors and psychotherapists are not there to diagnose, but we can sign post. We can help support someone who is maybe going through a diagnosis. If we do recognise that we are working with a client who is neurodivergent, it’s about individual centred approach.

One of the sayings is, if you’ve met one autistic person, then you’ve met one autistic person.

It’s tailoring the intervention to be unique to the person’s processing styles and sensory experiences.

It could include providing sensory accommodations or making, it might be a quieter room, or adjusting the lighting, or changing our communication style to suit what is better for the client.

And then, of course, we spoke last week about inclusive language, how important the language we use is and how important it is to find what the preferred language is for the person that we’re working with. That if they are on a road of neurodivergent diagnosis, or diagnosed, how do they choose to own that themselves?

If you take a moment and think what does an autistic person look like, how do they show up? What does that mean to you? Challenge that. Is that a stereotype? When we’re training, we learn about stereotypes and the danger of stereotyping that all Italians love pizza and anybody from Ireland loves drinking Guinness.

We move away from those stereotypes and we see people as individuals. So what does neurodivergence mean if you say it to yourself? And then, consider what are some of the challenges that neurodivergent clients may face within your sessions, and how could this impact their needs, and the way that you might react to that?

For me, those kind of topics are a week of sitting and reflecting on them, Rory. And then maybe discuss experiences, if you’ve had experience in working with a neurodivergent client, or clients, discuss that.

Maybe discuss it with your supervisor. Consider what strategies you worked with. What did you do that worked? What did you do that you felt didn’t work? And then finally, think about the language. What is the language you choose to use? If you’re going to be writing on your website that you warmly welcome neurodivergent clients, have you trained in that? Do you understand it? Are you able to offer that? And then what is the language you might use to bring that over? Any final thoughts on this, Rory?

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yes, I think this is such an emerging cohort of clients that we’re really only at the beginning of understanding what neurodivergence is.

It’s not, I’ve learned about that, now I know all about it. I think that in the next 10 years, in the next decade, we’re going to see more research, we going to find that more and more people are in fact neurodivergent.

It’s a continuing professional development. Really in the work we do, we have to do continuing professional development,

because the neurodivergent community, is a wide, broad church and what we’re not going to get is consensus on everything. So I think it’s honest of us to keep informed, keep our learning up, and to realise that this is going to be something that every therapist is going to encounter.

Ken Kelly: Beautifully said Rory.

That is a little bit of a deep dive into what is neurodivergence, and seeing beyond that label.

Diagnostic labels such as ASD help structure support systems and gain legal protections, but they can also lead to misconceptions that undermine a client’s individuality. Historically, labels like “high-functioning” or “low-functioning” emerged from early classifications of autism, including Hans Asperger’s work. However, these terms fail to capture the full complexity of neurodivergent experiences. Modern perspectives highlight that autism, for example, manifests in diverse ways, making labels overly reductive.

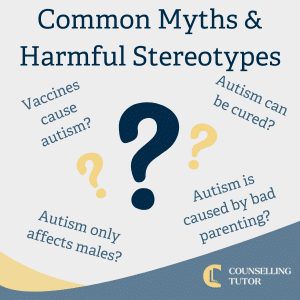

Research has shown that autism is not a rare condition but rather a spectrum that includes a wide range of behaviours, strengths, and challenges. Therapists should be wary of common myths, such as the idea that vaccines cause autism or that it only affects males. These misconceptions can influence public perception and therapeutic approaches, limiting the effectiveness of treatment and the support neurodivergent individuals receive.

One of the most essential steps in rethinking neurodivergence is addressing common myths about autism, which perpetuate harmful stereotypes. Here are the Top Ten Myths about Autism debunked:

Autism is quite common, affecting a broad range of individuals across different demographics.

Extensive research has thoroughly debunked this myth.

Autism is a lifelong condition, not something outgrown in adulthood.

While some have exceptional talents, such cases are rare.

Autism can affect individuals of any gender. Historically, diagnostic criteria favoured white middle-class males, which skewed perception and diagnosis.

Many individuals with autism form meaningful, empathetic relationships.

The outdated ‘refrigerator mother’ theory has been discredited.

Autism is a spectrum, meaning every individual experiences it differently.

Autism is not an illness, and therefore, there is no cure.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=znM-pDYIoWsMany autistic individuals thrive in various life areas, debunking this myth of incapability.

The concepts of “high” and “low” functioning have historically shaped the diagnosis and treatment of neurodivergent individuals, particularly those with autism. While initially developed to help clinicians understand different levels of need, these labels have been criticised for oversimplifying the autism spectrum. Clients labelled as “high-functioning” often find themselves denied necessary support, while those deemed “low-functioning” face stigma and reduced expectations in education, employment, and independence.

For practitioners, it’s vital to understand that these labels obscure the reality that all neurodivergent individuals may face significant social and emotional challenges, regardless of perceived intellectual or verbal strengths. The critical takeaway for therapists is to treat each client as unique rather than relying on generalised labels, which can create barriers to care and lead to unmet needs.

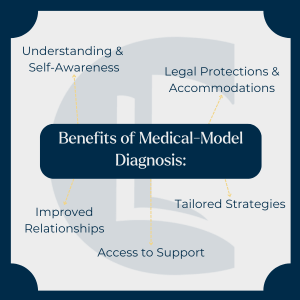

While labels have their limitations, receiving an autism diagnosis can provide numerous benefits, mainly when framed within a medical model. Key benefits include:

It is important to note that the decision to pursue a diagnosis should be client-driven, respecting the individual’s journey and autonomy.

Language plays a significant role in the therapeutic relationship, mainly when working with neurodivergent clients. Traditionally, clinicians have been taught to use person-first language, such as “person with autism.” However, many in the autistic community now advocate for identity-first language, preferring terms like “autistic person” or even “autist.” This preference affirms that autism is an integral part of their identity rather than something separate or abnormal.

Therapists are encouraged to ask clients how they prefer to be addressed, recognising that preferences vary widely. A simple question—whether the client chooses “autistic person” or “person with autism”—can enhance rapport and demonstrate respect for the client’s identity.

The legacy of Hans Asperger, after whom Asperger syndrome was named, has become ethically contentious. Research revealed Asperger’s collaboration with the Nazi regime, where his classification of “high-functioning” and “low-functioning” children contributed to eugenics programs. This history complicates the continued use of functioning labels.

Many neurodivergent individuals, especially those diagnosed with Asperger syndrome, may find these historical revelations upsetting, as their diagnosis forms an integral part of their identity. As professionals, it is essential to be sensitive to these concerns and the potential emotional impact on clients.

The history of autism classification presents additional challenges for therapists. The legacy of Hans Asperger and his collaboration with the Nazi regime complicate this, his work contributing to eugenics-based practices. While some continue to view Asperger’s as a figure who helped specific neurodivergent individuals, these revelations add complexity to the use of terms like “Asperger syndrome”.

This historical context emphasises sensitivity when discussing diagnoses with difficult or painful connotations. Practitioners should be mindful of historical factors affecting current diagnostic practices and how clients might feel about terms linked to harmful legacies.

As you apply these insights in your practice, consider these reflective learning tasks:

These reflections will help create a more inclusive and respectful therapeutic environment for your neurodivergent clients.

Seeing the Individual Not the Label – Rethinking Neurodivergence

As a counsellor or psychotherapist, moving beyond diagnostic labels and truly seeing the individual before you is essential. Recognising the diversity and complexity of neurodivergence will enable you to provide more effective support. By challenging common stereotypes, debunking myths about autism, and adopting a client-centred approach, you can offer more empathetic and tailored care.

The shift away from terms like “high-functioning” and “low-functioning” reflects a deeper understanding of the autism spectrum as varied and dynamic. This change enhances your therapeutic interventions and addresses the ethical concerns of historical figures like Hans Asperger. Being mindful of this history will help you approach each client with sensitivity.

By embracing updated diagnostic frameworks and respecting your clients’ language preferences, you’ll help them feel seen and valued. Understanding the benefits of a formal diagnosis—such as access to support, legal protections, and greater self-awareness—can guide you in supporting clients without pushing them toward a label they may not need or want.

By meeting the learning outcomes from this article, you’ll be better equipped to offer meaningful, informed support. You’ll be able to recognise both the unique challenges and the potential for growth in every neurodivergent client, helping them thrive in ways that are right for them.

Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Leo Kanner, Hans Asperger, and the discovery of autism. The Lancet. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)00337-2/fulltext

Gillette, H. (2023). Understanding Why the Term ‘Asperger’s’ Is No Longer Used. Healthline. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/autism/why-is-the-term-aspergers-no-longer-used#summary

McCarthy, J. (2018). Rain Man at 30: Damaging Stereotype or ‘the Best Thing That Happened to Autism’? The Guardian. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/dec/13/rain-man-at-30-autism-hoffman-cruise-levinson

National Autistic Society. (2023). Asperger Syndrome (‘Asperger’s’). National Autistic Society. Available from: https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/what-is-autism/the-history-of-autism/asperger-syndrome

One Central Health. (2020). 10 Myths about Autism Spectrum Disorder. Available from: https://www.onecentralhealth.com.au/autism/10-myths-about-autism/

Sher, D. A. (2020). The Aftermath of the Hans Asperger Exposé. The British Psychological Society. Available from: https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/aftermath-hans-asperger-expose

Turda, M. (2023). Confronting Eugenics. The British Psychological Society. Available from: https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/confronting-eugenics

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us