Autism-Informed Practice Course

Gain the Knowledge & Skills to Support Autistic Clients with Confidence & Compassion

The following article is taken from our Autism-Informed Practice course.

Gain the Knowledge & Skills to Support Autistic Clients with Confidence & Compassion

In therapeutic work, especially when engaging with neurodivergent individuals, communication challenges can deeply impact the therapeutic process. The Double Empathy Problem, a concept introduced by Dr. Damian Milton in 2012, offers a valuable lens through which therapists can approach interactions with autistic and neurodivergent clients.

This theory proposes that communication gaps between autistic and non-autistic individuals are bidirectional, originating from differing cognitive frameworks rather than a single party’s deficits. This blog explores the Double Empathy Problem and its implications for practitioners, with practical advice on creating an inclusive and understanding therapeutic space.

The Double Empathy Problem in Neurodivergent Therapy

By the end of this article, you will:

Ken Kelly: Understanding the double empathy problem in neurodivergent therapy. What is the double empathy problem?

Rory Lees-Oakes: It was a concept introduced by Dr. Damien Milton in 2012. It basically states that when we engage in neurodivergent individuals, we can have challenges.

So it might be that the understanding of a neurotypical person is markedly different to that of a neurodivergent person. You may say to somebody, a neurodivergent person, can you pass the salt? And they go, yes. And don’t pass it to you because they think you’re speaking about their ability to give you the salt pot, not the underlying question, which is, please give me the salt pot.

We can find that things like simile, a metaphor, maybe a bit of a challenge for those who are neurodivergent because, it might not be clear enough.

When we work with clients, we have to be very thoughtful of being really clear in our communication and making sure that what we say is understandable. We cannot rely on shortcuts in our syntax because they may be misinterpreted.

Ken Kelly: Thank you, Rory. I see myself falling under this double empathy problem within my home life. My wife is neurodivergent as well, and we can talk for some time and have an in depth discussion,

and the interesting thing is we can both leave, having had two separate discussions because of the way our frame of reference wrapped around the topic we were talking about. It can cause a challenge when an expectation wasn’t carried out either way because of a misunderstanding.

And that’s what it boils down to. It boils down to misunderstandings. This is what we’re trying to eliminate as much as we can within a therapeutic session. If we’re opening our doors and saying that we are happy to invite in a neurodivergent client, then we need to learn what are the barriers of communication.

And I think that the double empathy problem falls beautifully into a barrier of communication. To simplify it, I would put it into two separate frames of reference. Can you pass the salt? Yes, I can. I have the ability to pass the salt.

Then, will you give it to me, please? Oh, here it is. And then that person might be quite irritated. I asked you to pass me the salt. And the neurodivergent individual might say, No, you didn’t. You asked if I could. And I answered you. Yes, I can. And therein is a misunderstanding

Oh, I see, you’ve put all your eggs in one basket or you’re juggling a lot at the moment. It could be interpreted literally. I don’t know how to juggle. Why are you talking about eggs? So we want to be recognising that there is a double empathy problem.

My wife might be on her way to work and say, would you be able to put the bins out today?

I might say yes. Then she might come in that evening and say did you put the bins out? And I say, no, but you didn’t tell me to. You just asked if I could and of course I can. I had the time. You should have asked if you’d wanted that. I don’t know if this is just a very cunning excuse that I’m coming up with, Rory.

It’s just a made up example of double empathy problem. And I guess, Rory, when we look at this, There is oppression and psycho-emotional harm that can arise from this. And I think this is the important point that we should maybe look at now.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yes, the thing is, we shouldn’t be forcing or helping our clients to be neurotypical.

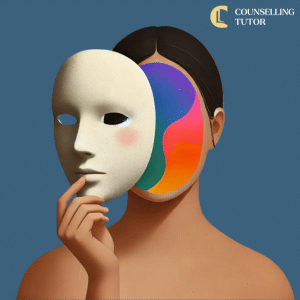

They are who they are. They have their own frame of reference, and I think this term psycho-emotional disablement was highlighted by Damien Milton’s co-writer of the paper, historically, those people who are neurodivergent were taught to be neurotypical.

They were, and if there was ever a case supporting a square peg in a round hole, that might cause some neurodivergent people a bit of confusion. You’re trying to make people fit into a rigid framework of neurotypical thinking when in fact, they think in a very unique way and have every right to think in that way.

It’s up to us as therapists to be mindful of our communication and make sure that we’re communicating really clearly. When we’re working with children, we use what’s called clean language. In other words, language that can’t be misinterpreted. And I think the same idea here is really important.

If you’re in a therapy session, you might say to a client, do you want to take a seat? That could be confusing couldn’t it? Where do I take the seat to?

Ken Kelly: Yeah, so we’re looking to reduce ambiguity here, to make things crystal clear.

A neurodivergent individual may not be able to read social cues that are given off, maybe with an eye movement or facial expression. I’m going to take an example where a neurodivergent individual may have an area of interest that they find absolutely fascinating and can speak for hours on it.

If they were speaking about their special interest to a person, and that person was maybe bored and trying to show with their body language that they’ve had enough, it may be difficult for that neurodivergent individual to recognise that, unless the person specifically said, you know what?

This is really great, thank you very much for sharing so much, but that’s as much as I can absorb right now. Can we leave it there?

One person may be feeling uncomfortable in a situation, the other person not realising that, being passionate about what they’re talking about, and continuing to talk about that. So neurodivergent individuals generally will appreciate honesty and simplicity in what is being asked.

And a double empathy problem doesn’t just restrict itself to a neurodivergent-neurotypical conversation.

Of course, we’re applying the theory here, but we see it often within a working environment where a task might be set for a certain person, when that task comes for delivery and the person has maybe done it incorrectly or hasn’t done it at all, only then is the discussion had of, but you didn’t say you needed it that way and this way.

And only then does it come out what the real understanding was. With barriers to communication, we are looking to reduce those as much as we can, within counselling and psychotherapy. When that client is in front of us, if that person happens to be neurodivergent, we need to be mindful of how we speak, not to use metaphor, maybe not to use simile, and speak to the individual, see how they feel about that and regularly check your understanding of what they are saying, but also their understanding of how you are reflecting back and what you are adding as the therapist within the conversation.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, absolutely. I think therapy should be curious. And I think one of the biggest challenge with clear communication, certainly in the person centered tradition, is an idea that we should only use questions to clarify things.

With neurodivergent clients, we may have to adapt our questioning style to some extent and use what’s called Socratic questions. So what would happen if, or, very direct questions.

So I guess the Socratic question will be, what would happen if you didn’t get this job, and the person may respond and say I would look for something else.

It’s not something we do usually in person centered therapy, but I think we might have to adapt our questioning style to make sure we’re getting across that clear communication where we can be on the same page.

Ken Kelly: Yeah, and it’s the recognition everybody is going to come as they are. And it’s about us being curious, checking regularly with our clients, asking the client to be part of creating how we work.

If we’re looking to train in welcoming a neurodivergent individual into our practice, we have to look outside of that. We have to adapt our communication and our approaches. We have to evaluate the modality that we were using.

Being purely person centered, we might use questions very sparingly, it may be that we need to adapt. Is this appropriate for the client I’m working with? We need to do some critical thinking, as practitioners, we need to build that empathy.

How do we do that? We do it through curiosity, really caring about what that person is sharing with us, where they’re coming from, and understanding how they may be. The double empathy problem reminds counsellors and psychotherapists that empathy is a mutual endeavour that requires flexibility, curiosity, and a commitment to seeing beyond neurotypical norms. So we’re actually growing a little bit outside of the norms and as therapists, embracing bi directional empathy enables us to create a supportive environment for neurodivergent clients.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, so I think that we use so much shortcuts in language. I do it all the time, I use metaphor and simile all the time. And I think sometimes, we do it without thinking.

Because our communications forged like that from a very early age. And I think when we are using language, it’s always good. Not just with neurodivergent clients, but any client, to think about how clear our language is. Maybe that’s an area of personal development, one that could be discussed with your supervisor.

How often do you use little linguistic shortcuts in the hope the other person knows? Sometimes, it could be confusing for neurotypical people. Think about how we communicate and just think how clear our communication is. Think clean language as we would do if we were talking with children.

Dr. Damian Milton’s Double Empathy Problem theory suggests that communication difficulties between autistic and non-autistic people arise from differing perceptions and experiences of the world. This difference often results in a dual-frame situation, where each person may struggle to understand the other’s perspective. Milton challenges the notion that empathy deficits are specific to autistic individuals. He highlights that non-autistic people frequently find it difficult to empathise with autistic viewpoints as well.

Consider a scenario where someone mentions, “I had a bat in the back of my car.” This might evoke an image of a baseball or rounders bat, aligning with general societal expectations for a non-autistic person. An autistic person, however, might interpret this as a small nocturnal animal, given that these implicit social assumptions don’t shape their worldview.

This disparity underscores the importance of clear, context-aware communication that checks assumptions and confirms mutual understanding.

The concept of psycho-emotional disablement, highlighted in Milton and Lyte’s work, refers to the psychological harm caused by forcing neurodivergent individuals to fit within rigid, often non-autistic frameworks. Historically, therapeutic approaches have attempted to “normalise” autistic behaviours through interventions like Applied Behavioural Analysis (ABA).

This inadvertently reinforced the idea that autistic individuals are “broken” or “abnormal.” This approach can contribute to internalised oppression, where clients begin to feel that their natural ways of being are inherently flawed. Such feelings can exacerbate stress, anxiety, and depression, posing significant barriers to therapeutic progress.

Neurodivergent clients benefit from a co-created, flexible therapy environment that does not impose neurotypical norms as the standard. Therapists can ensure they remain aligned with their client’s unique needs by encouraging open discussions on communication preferences and regularly confirming understanding.

Counsellors may need to adapt their communication methods, such as using verbal and nonverbal cues, simplifying language, or providing visual aids. Asking clarifying questions is helpful to avoid misunderstandings and demonstrate an openness to different interpretive frameworks. For example, in person-centred therapy, traditionally low on direct questioning, therapists might need to adopt a more Socratic approach to gain a clearer insight into the client’s worldview.

Traditional therapeutic methods, including ABA, have received criticism for attempting to alter neurodivergent behaviours rather than adapting to them. As a therapeutic community, we are urged to reassess whether our methods serve the client’s needs or inadvertently attempt to conform them to neurotypical standards. Consider whether your approach respects neurodivergent perspectives, avoiding rigid normative pressures. Neurodivergent clients should feel validated in their uniqueness, just as a therapist would accommodate a physical disability with accessible facilities.

Developing a collaborative approach to empathy is vital. Practitioners should cultivate curiosity about neurodivergent ways of thinking, using Socratic questioning to explore clients’ unique perspectives. By encouraging clients to share their interpretations openly, without fear of judgement, therapists create a sense of safety and mutual understanding.

This bi-directional empathy helps bridge the communication gap, ensuring that both client and therapist are on the same page. This is a foundation for meaningful therapeutic work.

Understanding the Double Empathy Problem in Neurodivergent Therapy

The Double Empathy Problem reminds counsellors and psychotherapists that empathy is a mutual endeavour that requires flexibility, curiosity, and a commitment to seeing beyond neurotypical norms. As therapists, embracing this bi-directional empathy enables us to create a supportive environment for neurodivergent clients. This helps them to feel understood, respected, and valued for their unique perspectives. By critically assessing and adapting our practices, we can move toward more inclusive therapy that honours neurodiversity as a part of the human experience.

This approach provides a pathway for practitioners to meaningfully engage with neurodivergent clients, offering insights to bridge communication gaps and create stronger therapeutic relationships.

Milton, D. A. (2012a). On the ontological status of autism: the Double Empathy Problem. Disability & Society. Available here.

Milton, D. A., & Lyte. (2012b). The Normalisation Agenda and the Psycho-Emotional Disablement of Autistic People. Autonomy: The Critical Journal of Interdisciplinary Autism Studies. Available here.

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us