Your FREE Handout

Structural and Functional Models of Ego States

The psychoanalytical school of psychology can trace its roots back to the mid-1800s and the work of Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis – and, arguably, of talking therapies in general.

Indeed, Sanders (2002: 15) writes: ‘No contemporary psychologist or psychotherapist could claim not to be influenced by the work of Freud.’

Structural and Functional Models of Ego States

Freud believed that humans had a subconscious part of their psyche that could in some cases cause individuals to experience ‘neuroses‘, which presented as a number of negative feelings, such as anger, anxiety, depression and low self-worth.

‘Neurosis’ is no longer used in the language of therapy. It has been replaced by an overarching term, namely ‘anxiety disorder’.

The psychoanalytical approach to therapy is still taught and practised today. However, modern practitioners – having access to research accumulated after Freud’s death in 1939 – work in a contemporary way.

Unlike Freud, they consider the relationship between client and therapist as an important part of the therapeutic alliance or relationship.

Freud, meanwhile, referred to his clients as ‘analysands‘ and advocated that the therapist should remain objective. Therapy generally took place with the client lying on a couch, unable even to see the therapist. Most early psychoanalysts (including Freud himself) were medical doctors.

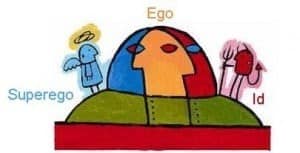

The basic tenet of Freud’s ideas still remains: that as humans, we are driven by three distinct drives that need to attain balance: the id, the ego and the superego.

While some people see these as sections of the mind, Freud meant them not as some kind of physical containers but as functions of the mind, which can pull us towards different behaviours.

The id pursues our desires and is fuelled by ‘libido‘ (the Latin word for ‘desire’ or ‘lust’, which Freud used to refer to our desire to procreate, that is the instinct-based energy associated with the human sex drive).

Feltham and Dryden (1993: 87) define ‘id’ as ‘the deepest part of the subconscious, a well of libidinous, chaotic, amoral, uncivilised energy’.

The ego, meanwhile – which is ‘the conscious and reasoning part of the mind’ (Feltham and Dryden, 1993: 57) – mediates between the id and the superego, which is ‘concerned with self-criticism, self-observation and idealism’ (ibid: 186).

Freud asserted that the id is formed by a mixture of innate and learned aspects, while the ego emerges from the id as a reality-testing mechanism that allows us to behave more appropriately in the world.

The superego, meanwhile, is seen to be a product of introjecting parental values and rules (and thus could be compared to conditions of worth – giving rise to the ideal self – in the person-centred tradition).

To use an everyday analogy to illustrate this, if faced with a large chocolate cake that we were attracted to eating, the id would have us eat the whole lot in one go, the ego would suggest we have one moderate-sized piece a day, and the superego would tell us to eat an apple instead.

One of the consistent themes in the psychanalytical approach to psychology is that of the presenting past: the idea that our here-and-now difficulties are rooted in past events (maybe in childhood) of which we are unaware.

Differing schools of psychoanalysis have emerged over time.

Indeed, going back to Freud’s lifetime, a number of Freudian revisionists – that is, those who, having been attracted to and initially having accepted the ideas of Sigmund Freud, later broke away - developed their own version of psychoanalysis.

Some well-known Freudian revisionists include Alfred Adler, Carl Jung, Melanie Klein, Wilhelm Reich and Donald Winnicott (Sanders, 2002: 15).

One of the most well-known schools of psychoanalysis in the modern day is transactional analysis (TA).

TA was developed in the 1950s by Eric Berne, who wanted to demystify therapy by using what he described as ‘layman’s language’.

TA therapy replaced the Freudian idea of superego, ego and id with the terms ‘parent’, ‘adult’ and ‘child’.

Berne contributed to child development theories by introducing the term ‘life script’, which describes the idea that when children are as young as four or five years of age, they subconsciously produce a life plan based on their interaction with care-givers.

This links with another of his theories that as children, we take on ‘injunctions‘.

These are subconscious messages from our care givers that lead to us developing a coping mechanism called ‘drivers’, which help us attain emotional balance in the world.

Structural and Functional Models of Ego States

Feltham C & Dryden W (1993) Dictionary of Counselling, Whurr

Sanders P (2002) First Steps in Counselling: A Students’ Companion for Basic Introductory Courses, PCCS Books

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us