Your Free Handout

Supporting Bereaved Children: A Guide for Counsellors and Psychotherapists

Grief and bereavement in childhood can have profound and lasting effects on a young person’s emotional and psychological development. As a counsellor or psychotherapist, understanding how children process loss and providing appropriate support is essential in encouraging resilience and healthy coping mechanisms.

Bereavement can disrupt a child’s sense of security and normalcy. Children who have experienced the death of a parent, sibling, or close friend might be more likely to experience mental health issues, behavioural challenges, and/or difficulties in education. Therefore, the proper knowledge and techniques are critical to effective therapeutic intervention.

This guide will provide an overview of key concepts in child bereavement, practical strategies for working with grieving families, and creative techniques to support children through their grief journey.

Supporting Bereaved Children: A Guide for Counsellors and Psychotherapists

By engaging with this guide, you will:

Ken Kelly: An important topic, talking to children about death.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, absolutely, Ken. And this has been generated from a conversation that I’ve had within my family. I have a granddaughter, and she’s gonna be five very shortly, and she’s started to ask the questions around death, what is death? And she saw some flowers at a scene of an accident and asked, Mum, what happened?

And I think it’s also something that appears in the therapy room. It may be a client is struggling to talk about the death of their partner to the child, or it may be if you’re a child therapist, this comes up. There’s lot of good advice about and, I ‘ll first start off by saying, I think in general, talking to children about the circle of life is a wonderful thing, just observing growth and death in life.

And that could be plants, it could be the trees shedding the leaves. And I think having those conversations of life being cyclic with children is really useful by showing examples, pets that have died. And I think introducing that topic in a very supportive way, but in a very kind of normalised way.

Because the fact of the matter is, we have a circle of life. People are born, they live and they die.

I think that some of the advice actually is quite interesting. And if a child asks you directly, I’ve had a look at a lot of charities, they’ve said, talk about the more physical aspects of it. The fact that the lungs stop working, the brain stops working, the heart stops working, and at that point, the person is no longer a person. And I guess as a parent myself, I would only share as much information as was asked for.

Don’t overcook it because children can only take in so much. It’s a very delicate subject. And it can also lead to specific psychological presentations from children. And one of those, Ken, is magical thinking. Where children may believe that in some way they’ve contributed to the death of a parent or a loved one.

And it has to be handled very sensitively. I guess as parents, we’ve both had this conversation at some point, Ken.

Ken Kelly: Yeah. It’s an important topic and I’ve referenced a lecture that is in the Counselling Tutor CPD Library.

It’s Nicola Hughes and it’s Children and Loss is the name of the lecture. And when we’re speaking about children loss, death, grief, there is the way that you’ve just introduced this topic, Rory, of having that discussion as a parent or a significant other in a young person’s life.

But there’s also the other side of that where we may be seeing this post somebody passing away and just to share some statistics. And this is from child bereavement.org, and it’s the death bereavement statistics. And these are sad numbers, but they are true numbers. A parent of a child under 18 dies every 22 minutes in the UK, that’s around 23,600 a year, and it equates to around 111 children being bereaved of a parent every single day.

So this is something real, this is something happening, and it is something that we may come into contact with, maybe from a client asking how they would work with their child if they’ve lost someone significant within the family.

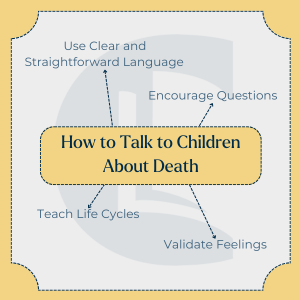

Or if you’re working with children and young people, you may be working with the child themselves. You mentioned the wishful or the magical thinking, and I think what it is when we are speaking about death to a child, whatever those circumstances may be, we wanna be steering clear of euphemisms.

Steering clear of using words that don’t really depict what has happened. So euphemisms are, popped his clogs, resting in peace, in a better place, star in the sky, And the reason that we don’t use these sayings that we as adults can understand is because this can be taken quite literally by the child.

It can lead into that fantasy thinking where the child still feels that person is around at some level that they might see them again. And what we’re called on to do in this situation is we need to be as honest and as direct and as plain as we can be.

And that would be dependent on how old that child is and what their ability to understand is. But I think by being honest and open and just saying how it is. The child will look to the other significant adult in their life, so if somebody has been lost in a family, the child will look to the other members of the family as significant others and will take their understanding of the grieving process and of death from those others.

And it may well be those others that we might end up working with within our sessions, Rory.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, absolutely, Ken. And I think I’ll pick up on your points on the euphemisms and the magical thinking. I’ve got a couple of friends who lost their parents after they’d had an argument.

So they’d had a very big argument with mum, and went out and then came back and mum had died. And he carried it right through his childhood into his adulthood, and believes somehow that his words had caused death.

And that, if he hadn’t had that argument with mum, mum might be alive. And, certainly for younger children, this can be a very real phenomena, they can believe that what they’ve said, they’ve been naughty, and as a consequence, a parent has died.

And also with euphemisms, when people say we’ve gone onto the other side, certainly a child of my daughter’s agents say, where is this other side? Can I go to this other side and see them? So we have to be very careful.

And I think it’s a good time actually to bring up neurodivergent children, children who may be autistic. They would struggle with euphemisms even more, Ken, because some neurodivergent children don’t have the subtlety, some neurodivergent adults don’t have the subtlety, to be able to separate euphemism from actuality. So we have to be very thoughtful, and very child age appropriate.

I think that, if you’re working with say, under fives, there are some behaviours that we could pick up. They may sense the loss without understanding death, and they may become clingy, withdrawn or need more comfort, and also regressing behaviours. So things like bedwetting are very common.

So those are the kind of things to look out for because they don’t have the life experience or the kind of cognitive development to be able to conceptualise death? Really, who does? It’s such a huge thing, isn’t it? When someone you love dies.

And, over five, five to 11, they may ask repetitive questions. So it may be they asked about how someone died, are they coming back? And those questions, you may say I’ve already answered those, but it’s not so unusual for children to keep asking those questions. And I guess what they’re looking for is some form of reassurance to try to conceptualise what’s happened.

And acting out, I always really have a strong reaction to where people say the child’s acting out. What they’re trying to do, is that their behaviour is reflecting their inner world. And if someone’s acting out, my rule of thumb here is all behaviour is goal directed.

You just need to understand the goal. Once you understand the goal, you understand the behaviour, Ken.

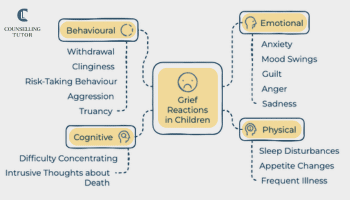

Ken Kelly: Yeah, very much and the kind of behaviours that we may see, withdrawal, regression, becoming clingy, behavioural problems where the child goes out of character and develops problems that we haven’t seen before, [00:08:00] risk taking behaviours that can be harm to self, poor punctuality, truant, difficulties with concentration and learning, preoccupied, forgetful, hitting out. So these are all possible reactions to grief. And I think that we don’t only see these in children, I think this is part of being human.

Grief is a natural process. It is a natural process and one of the things we need to recognise is that with grief being such a natural process, not everybody’s gonna reach out and not everybody needs specialist intervention and help to get through grief because it is something that humans have been going through since the dawn of time and will continue to go through.

But we do the CPD so that we are aware that when somebody does come and look for some help, that we understand this topic at enough depth to be able to serve, and be there with that person. And, you spoke about the thoughts that can play out, that a person might be left with, and these are the kind of thoughts that can carry on right from childhood into adulthood, and be a script that kind of informs how the person will live out their life.

It’s my fault that they died in some way, I was part of that. It may be a, I can’t create bonds with people because all the people I care about eventually are just gonna die, and I know how painful that is, so I’m going to avoid that by avoiding closeness with others.

There could be almost a, why did you leave me? There can be an anger, that person has left me, this world is not a fair place, the world is not as safe place for me. And these can be reenacted as adults.

And we’ve said so often, Rory, when our client is in the room, if that’s a grown adult in our room, we’re also working with the child and everything that child has gone through within their life.

And you mentioned, Rory, possible ways of working with a child and films work for children. Even the Lion King, there’s death in The Lion King, and it’s a way of developing understanding. I remember Bambi was of my time, with the little buck, and its mum passed away, and it was really sad. It was sad as a child to watch it, but it does at some level show that circle of life, as you said, Rory. There are really good books available that kind of speak about the circle or the pathway of life.

There’s quite a lot here that I’ve been able to take from Nicola Hughes’s lecture on this topic. Because she goes really deep into this. And if you’re a member of the Counsellor CPD library, log in and just search children and loss and go and watch that CPD lecture, it’s about an hour long, but it’s really detailed and really useful.

Any other thoughts on this, Rory?

Rory Lees-Oakes: Don’t avoid talking about death. I think that it’s one of the great taboos. When I grew up, no one talks about sex or death. You talked about it and you were considered impolite. And seems to me through the last 40 years people are quite happy to talk about aspects of their sex lives or their emotional lives.

But when it comes to death, we are probably not as communicative as other countries. In Mexico, I believe they have something called the Day of the Dead, where they celebrate death. They remember death. We tend to not in the UK.

So if you’ve got children, sit there, have the conversation.

Because I think if it’s not discussed, then it will come back. The child becomes the adult, it can be something that they’ll carry through their life. So, let’s have a more open conversation about something that’s a real natural phenomenon. It’ll happen to all of us, Ken. Not today, but it will happen to all of us.

Ken Kelly: Yes, and as we come to the end of this, I wanna share something that I think is really useful, and it’s based on William Wooden’s 1996 study, which was a two year study and it’s called The 12 Needs of a Bereaved Child.

A child needs clear, comprehensive information about death. That’s where we started this topic. A child needs to be allowed to express feelings that they have, and the fears that they have, and the anxieties soothed around those. A child needs reassurance that they are not responsible for the death, they need to be told directly and reassured that they weren’t part of that, and that this is something that happens in life.

A child needs to have someone who will listen attentively so that their feelings will be acknowledged and respected, and you spoke about the different ages and what the understanding at those ages might be. And even at those younger ages, we may think, oh they don’t fully understand it, but they still need their thoughts and feelings validated. It’s so important.

A child needs help gaining perspective of their own emotions and to understand that it’s okay and that it does take a little bit of time. A child needs to be involved and included in open grieving, the child will look to the other caregivers and the other family members to see how they grieve, and they will take their cue from there.

So we don’t want to only do our grieving while the child is locked away. We want to do that openly to show that this is natural and normal. A child needs permission to continue with interests and activities. The world doesn’t stop. They can still go play with their friends, go to the park, go and play football, go to their dance lesson, whatever it is.

A child needs to see other people grieve and learn how grief works in the group that they belong to. A child needs an opportunity to say goodbye to the person who has died and have opportunities to remember that person throughout their lives.

And I think that’s so important. When we experience loss, and I’ve certainly experienced my fair share of loss, we are left with the memories of those people. And revisiting those memories and remembering that person.

A child needs reassurance, that they will be cared for, that they’re gonna be okay. That person has gone away and they’re not gonna come back, but it’s okay. Somebody loves them, and somebody’s got them and will hold them. And number 12, a child needs a safe companion to respond to their questions. No matter how many times they ask those questions, or how many questions they have, to have that patience and be there for them.

Great topic, thank you very much, Rory.

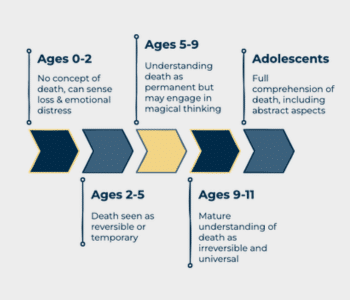

Children’s comprehension of death changes as they develop:

Tailoring conversations and interventions to the child’s developmental level is crucial to ensuring that the child feels supported without being overwhelmed.

Many adults struggle with discussing death, often resorting to euphemisms such as “gone to sleep” or “lost.” However, these can be misleading and cause confusion.

Best practices for discussing death with children include:

Children express grief in varied ways, which can be behavioural, physical, cognitive, or emotional:

Counsellors should observe these reactions closely and provide a safe space for children to process their emotions.

Many children misunderstand death due to the euphemisms used by adults. Phrases like “gone to sleep” or “lost” can lead to confusion, anxiety, and even fear around sleeping or separation. When assessing bereaved children, exploring the language caregivers use and gently challenging unclear or misleading explanations is important.

Supporting Bereaved Children: A Guide for Counsellors and Psychotherapists

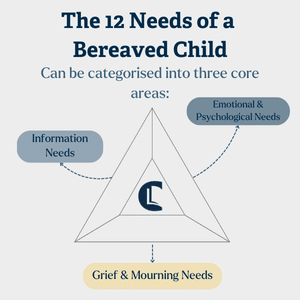

William Worden’s research, supported by findings from the Harvard Bereavement Study and the Childhood Bereavement Network (CBN), outlines twelve essential needs for grieving children.

These needs can be categorised into three core areas: Information, Feelings, and Grief.

Grief and bereavement in childhood can have profound and lasting effects on a young person’s emotional and psychological development. As a counsellor or psychotherapist, understanding how children process loss and providing appropriate support is essential in encouraging resilience and healthy coping mechanisms.

Counsellors should observe these reactions closely and provide a safe space for children to process their emotions.

Supporting caregivers in meeting these twelve needs is as essential as working directly with the child. Counsellors can guide parents, teachers, and family members to ensure these needs are met, creating a healthier grief process.

Grief affects the entire family system. Parents and caregivers play a critical role in a child’s adjustment to loss. The functioning of the surviving parent is a key predictor of the child’s ability to cope.

Interventions for parents may include:

A family-focused approach ensures the child and their caregivers receive the necessary support.

Counsellors working with grieving families should recognise that parents may be struggling with their grief, making it difficult for them to support their children effectively.

The Good Enough Grieving Parent model suggests that parents should receive:

When working with bereaved children, setting clear expectations is essential. A contracting box can be a creative way to introduce the therapy process. Items in the box can symbolise different aspects of the counselling work:

This approach helps children feel in control of the process while making abstract counselling concepts tangible.

Children often struggle to articulate grief verbally. Using creative interventions can help them process their emotions.

Some effective techniques include:

These methods provide children a structured way to express and make sense of their grief.

Supporting Bereaved Children: A Guide for Counsellors and Psychotherapists

Counsellors must understand a child’s stage of cognitive and emotional development – for instance, younger children may not fully grasp death while adolescents might ask existential questions. Adjust communication so it aligns with the child’s frame of reference.

Bereavement affects the whole family system. It’s vital to explore changed family roles, parental capacity to support the child, and whether others in the household also need therapeutic support alongside the child.

If grief reactions persist in intensity (e.g. extreme withdrawal, loss of interest, regressing behaviour, or thoughts of joining the deceased), or disrupt daily functioning long‑term, referral for clinical therapy or group support is appropriate.

Counselling bereaved children requires a compassionate, informed, and flexible approach. By understanding their developmental needs, grief responses, and the role of family support, therapists can create meaningful interventions to help them navigate loss.

A crucial question in bereavement counselling is, “Why now?”. Families may seek counselling weeks, months, or even years after a loss. Understanding what has prompted them to seek support—behavioural changes, a significant anniversary, or external pressures—can provide insight into their needs and readiness for therapy.

With the right tools and knowledge, therapists can make a lasting, positive impact on grieving children on their journey through loss.

Child Bereavement UK – www.childbereavementuk.org

Winston’s Wish – www.winstonswish.org

Counselling Tutor provides trusted resources for counselling students and qualified practitioners. Our expert-led articles, study guides, and CPD resources are designed to support your growth, confidence, and professional development.

👉 Meet the team behind Counselling Tutor

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us