Trauma Informed Practice Course

The Competence and Confidence to Work with Trauma in Your Practice.

The following article is taken from our Trauma-Informed Practice course.

The Competence and Confidence to Work with Trauma in Your Practice.

Working with traumatised clients presents unique challenges and opportunities for counsellors and psychotherapists. Trauma disrupts a person’s sense of self and their ability to regulate their nervous system, often leaving them fragmented and disconnected. Building relational depth with such clients is essential for facilitating healing and reintegration.

This article explores the importance of the therapeutic relationship in trauma work, drawing on concepts from polyvagal theory and embodiment practices to enhance therapists’ effectiveness.

Relational Depth: Healing Traumatised Clients

Ken Kelly: Relational depth, healing traumatised clients. What can you tell us?

Rory Lees-Oakes: I think the first thing I can say, with a degree of confidence, is that we see more trauma in the therapy room than ever before. Once we have a vocabulary for things, it becomes more apparent, and I think trauma is something that’s come into the consciousness of people, not only the word itself, but also how it represents in people. When people are traumatised, it’s not just a dysregulation of our thinking, it’s also a dysregulation of our physical being. And this is something that’s become more and more apparent through the years. With people like Bressa van der Kolk, who has written enormous amounts of information on how the body reacts to trauma.

Trauma is embedded in the body. So it’s really important, when we meet clients that are traumatised, we understand that this is a holistic approach, that we’re working with their thought processes and their experience, but also understanding that trauma is embedded in their bodies, and we can help them with that to a certain degree. And I think what is most important, is offering compassion. People forget what compassion means, it’s Latin, it means self and suffering. As a consequence we have to empathetically sometimes suffer with the client.

Ken Kelly: Wow. That is very profound, Rory. We’re speaking today about relational depth and how important that is in working with trauma. Like you say, Rory, it starts with that level of compassion and truly being there, those are the stepping stones of relational depth.

I want to share a definition of relational depth that we have here. This is Cooper, 2005, and it defines relational depth as a state of profound contact and engagement between two people, in which each person is fully real, and the other is able to understand the value of the other’s experience at a high level.

And I like that definition, it’s very beautiful. And if we look to the theory of person centered counselling, one of the conditions for facilitative change requires us as the counsellors to be congruent or real within the relationship. But there’s also a suggestion that maybe the client will be in a state of incongruence, at times. And I’m putting in at times because relational depth, it really is, it’s that magical, almost indescribable being in the flow, where you’re both meeting as humanity meeting humanity. It’s a very real and deep connection, and really valuable if we’re working with trauma.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Absolutely,

when we start to work with clients with trauma, we’re working beyond empathy. We’re moving into a phenomenological realm, where we’re experiencing the clients at a number of levels and points, I can’t emphasise enough that part of relational depth is moving with the client.

It’s almost like a piece of music where two instruments play in harmony, and one instrument plays slightly behind the lead instrument. That’s exactly what happens. When we work with trauma, certainly relational depth, if the client is sad, we respond with a voice that shows that sadness.

If the client feels joy at something, a breakthrough maybe, we reflect that joy and that speaks to the unconditional positive regard, which just isn’t in person centred therapy. I was reading some work on Heinz Kohut, and he was saying much the same thing, we meet with unconditional positive regard, we meet the client where they are and work with who they are and their experiences.

It shouldn’t be underestimated, the power of deep listening, the quality of the listening. This is emphasised time and time again, not only in the literature, but in a lot of the therapists, and colleagues I’ve spoken to.

The quality of the listening, the quality of the responses, is so important because that person is sharing an incredibly difficult part of their existence with another, and you have to be there. You have to be willing to absorb what’s being said both emotionally and physically in some cases, as Roger said, soil of a different kind, for the client to be able to reorganise themselves, to put themselves back together internally and emotionally, and go on into the world.

Ken Kelly: I love that soil of a different kind and it is rare indeed, you were speaking about the quality of the listening, and it just made me smile. When I started my studies if you’d have told me that there was different qualities to actually listening to somebody I think that I would have gone ahh come on. But having gone through the training, seen that in action, and felt it myself, it is so important. It comes with practice, and maturity within your practice, that there are different depths at which we can listen. As you’re speaking about this relational depth, we need to recognise what trauma is and how it presents.

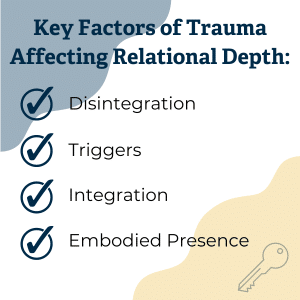

I want to speak about the enemies to that relational depth, and that would be the disintegration.

Trauma causes disintegration of self, and of nervous system regulation within the client. The other one is the triggers, and we spoke about this when we were speaking about neurodivergence, how we would be mindful of potential triggers like perfume in a room, or heavily scented flowers, or something like that.

Triggers, sensory triggers, smell, sound, can cause clients to relive that trauma. So what we’re looking to do is first of all, understand those. And rather than disintegration, which is the enemy of relational depth, we’re looking for integration, aiming to integrate the fragmented parts of the traumatised self and welcome them all into the therapy bubble. And how do we do that? We do this through an embodied presence. This is the responsibility of the therapist, this embodied therapist. It relates to the quality of the listening. It’s about really fully being there when we’re listening to this person.

We’re listening, not just to the words, but to the music behind the words, how is this person holding themselves? What are their eyes doing? What are their hands doing? How is their breathing? How are they presenting as a whole? We can enhance our embodied presence through understanding ourselves, our practice and what we’re looking at.

There’s a beautiful exercise we can do within the session with the client. The first is our posture. How are we sitting? Where are our feet?

Feet firmly on the ground gives you a grounding of self, feeling your back, being mindful in the moment, I can feel my back on the chair that I’m sitting on right now, Rory, but I have to be mindful and present to feel that. So it’s being fully present within the room.

As therapists, we can use breath work to bring ourselves into the here and now when we want to be fully engaged and right there with that client, just concentrating on how we are breathing, feeling the breath, go in and out of our nose. You’d think that it would be a distraction, but it’s not.

It grounds us in the present moment, because you can’t be somewhere else if you’re watching that breath coming in. That embodiment gives us a few little tools, or little techniques, that we can use to make sure that we are fully there for the client.

What’s important to bring this topic to a close, Rory?

Rory Lees-Oakes: I think that to work effectively with clients who are presenting with trauma, there’s a number of aspects to ourselves that we need to look at. First of all, clients will project onto us. I remember supervising someone many years ago, a female supervisee, and the client said to her, I’d been let down by women like you. And she was knocked back by that.

Coping with that projection, and being able to absorb it, is so important, because the clients will feel disappointment. They’ll feel pain and they’ll project it out. It’s really important that we’re very present and robust in the therapy room.

You spoke about being firm in the chair, what you were talking about, Ken is being regulated. One person in the room in trauma work has to be fully regulated, and that’s the therapist. I also think avoiding rescuing tendencies, certainly in the early forms of therapy, where a client’s talking about what might have happened, not trying to jump in and fix.

It’s important to allow clients to process their trauma without fixing them. Because what happens is if you say fixing, you effectively discount what they’re saying. You said you could try this, or you could try that, andthe full story and the process they’re engaging with is halted.

And it needs to move forward. It needs to come out. Avoid going very quickly in with interventions or fixes. Also managing personal dysregulation, recognise your process. I have heard some, quite frankly, terrifying stories through my 20 years of being a therapist. And one of the things I was very grateful for was personal development, groups, being able to separate out what was my stuff and what was the client’s. Also really good supervision, to allow me to put a respectful distance between myself and the client for my own well being. And that really speaks to regulating your own system. Speaks to maintaining a stable therapeutic presence. All the literature speaks to the fact that there’s two people in that room.

One needs to be present and regulated. And that, hopefully, at all times is the therapist, because if the two people become dysregulated, then you’re going to get two very unwell people. So don’t underestimate personal development. Don’t underestimate good supervision. And I would say don’t underestimate looking at the client load you’re taking on and how many traumatised clients you’re working with.

It’s usually good to spread the load out a bit so you’re not facing trauma every time.

Ken Kelly: Thank you, Rory.

Trauma can lead to profound disintegration of the self, and dysregulation of the nervous system. The therapeutic relationship is crucial in addressing these effects. Relational depth involves moments of profound contact and engagement between therapist and client, which can facilitate the reintegration of fragmented parts of the self and the regulation of the nervous system.

Cooper (2005, p. xii) defines relational depth as a ‘state of profound contact and engagement between two people, in which each person is fully real with the Other, and able to understand and value the Other’s experience at a high level’. This emphasises the significance of these moments in therapy. Such moments can happen anytime and are marked by a deep attunement in which time seems to stop, and a strong connection is felt.

Cundy (2017, p. 27) emphasises the importance of the therapist providing a secure base, which the client will experience as soothing and will internalise:

It is easier to internalise an experience that is repeated and predictable … and then when needed, he [the client] can call up on this new internal resource to calm and contain himself, to help him observe his feelings, impulses, and motives before acting, to create thinking space, and to challenge himself.

Embodiment practices are vital for therapists to maintain their presence and to support their clients’ healing processes.

These practices include:

Maintaining an upright posture to stay engaged and present.

Feeling the feet against the ground or the back against the chair to anchor yourself in the present moment.

Using breath to regulate the nervous system, such as full inhalations to increase energy, and straw breathing to elongate the out-breath and to engage the parasympathetic nervous system.

These practices help therapists to stay within their window of tolerance, a term developed by Siegel (1999) to describe the optimal state for relational depth.

Understanding the polyvagal theory is crucial for working with traumatised clients. The theory outlines three key modes of being:

Relational Depth – Healing Traumatised Clients

Building relational depth with traumatised clients requires a deep understanding of trauma, effective embodiment practices, and the ability to navigate complex therapeutic dynamics. By recognising and responding to different nervous system states and maintaining a grounded, present therapeutic stance, you can support your clients in achieving integration and healing.

Cooper, M. and Mearns, D. (2005). Working at Relational Depth in Counselling and Psychotherapy. London: Sage Publications.

Cundy, L. (2017). Anxiously Attached: Understanding and Working with Preoccupied Attachment. London: Karnac.

Levine, P. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Schore, A. (1999). Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self: The Neurobiology of Emotional Development. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

Siegel, D. (1999). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. New York: Guilford Press.

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us