Trauma Informed Practice Course

The Competence and Confidence to Work with Trauma in Your Practice.

The following article is taken from our Trauma-Informed Practice course.

The Competence and Confidence to Work with Trauma in Your Practice.

The Trauma Resilience Model (TRM) is a bottom-up, somatically based intervention that offers counsellors and psychotherapists a set of practical techniques to help clients stabilise themselves, particularly in the early stages of trauma therapy. It functions as a psychological first-aid tool, laying foundational work before deeper therapeutic processes can begin.

This method benefits clients prone to becoming overwhelmed or dissociating during therapy sessions, providing them with strategies to stay regulated.

This method benefits clients prone to becoming overwhelmed or dissociating during therapy sessions, providing them with strategies to stay regulated.

The TRM is anchored in neuroscience and designed to develop new neural pathways. This helps clients move from short-term cognitive coping strategies to long-term ways of being. This shift is crucial for trauma survivors, as it promotes resilience and emotional regulation, allowing them to manage internal and external triggers better.

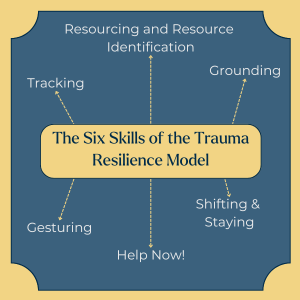

The six core skills of the TRM discussed here offer tangible techniques that can be easily integrated into your practice to support client stabilisation and long-term healing.

At the heart of the Trauma Resilience Model is the understanding of the nervous system. Particularly how sympathetic activation and parasympathetic release influence trauma responses. Drawing from polyvagal theory, TRM acknowledges the role of the sympathetic nervous system in activating the body’s fight, flight, freeze, or flop responses, often referred to as sympathetic charge.

When a trauma survivor is triggered, their body may quickly enter a state of red alert, preparing them for a defensive reaction. The challenge in therapy is to guide the client away from this charged state. The body can achieve calm through the parasympathetic nervous system, helping clients return to a place of stability.

The skills taught in TRM are designed to help clients recognise the onset of sympathetic activation and employ parasympathetic release techniques—whether through grounding, tracking, or other methods—to regain control of their emotional and physiological states. Over time, these tools expand the client’s resilient zone, creating greater emotional flexibility and reducing the likelihood of being overwhelmed by traumatic memories.

In the Trauma Resilience Model (TRM), every therapeutic journey begins with contracting—an essential process in which counsellors work with clients to establish realistic goals for therapy. This is particularly critical in trauma therapy, where clients may struggle with emotional regulation or dissociation. Contracting gives clients a clear map of what they hope to achieve, ensuring that therapist and client are aligned in their goals from the outset.

The importance of this process cannot be overstated, as it offers a shared understanding of therapeutic objectives. Moreover, as therapy progresses, clients may shift their focus or adjust their goals based on their evolving needs. Here, re-contracting becomes vital, allowing the therapeutic process to stay relevant and dynamic. You and the client can revisit and revise the goals together, ensuring they consistently address evolving needs.

This contractual approach is beneficial when introducing clients to TRM’s directive, task-based framework, especially when transitioning from more non-directive forms of therapy. A clear and mutually understood contract enables smoother integration of TRM techniques into the therapeutic relationship.

The Trauma Resilience Model (TRM) emphasises the importance of stabilising clients before moving into more complex therapeutic work. This model provides a structured, directive approach, helping therapists guide clients toward emotional regulation through somatic interventions. Below are the six core skills adapted for practical use in psychotherapy.

Tracking focuses on helping clients monitor their internal sensations. By identifying whether these sensations are pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral, practitioners assist clients in differentiating between distress and well-being. This mindful awareness helps clients take control of their emotional and physiological states, a critical first step in stabilising themselves during moments of activation or overwhelm.

For example, a therapist might ask, “What are you aware of in your body right now?”. This allows the client to focus on their felt sense and gain insight into the connection between physical sensations and emotional responses. The goal is to enhance the client’s ability to identify triggers and recognise their body’s signals before escalating into a stress response.

Resourcing encourages clients to identify positive resources—such as memories, personal strengths, or comforting images—that bring them joy and safety. These can include a beloved pet, a favourite place, or an activity they enjoy. Once identified, clients are invited to describe how the resource feels and the sensations they notice in their body.

By anchoring these sensations, clients can draw on these resources during moments of distress, thereby accessing positive emotions and stabilising themselves. This technique is vital in trauma therapy, as it helps clients shift from distress to safety by building a mental and emotional toolkit for managing overwhelming feelings.

Grounding focuses on present-moment awareness and physical contact with the environment, such as feeling the chair, floor, or skin. This tactile focus creates a sense of safety and control. Grounding techniques often serve as a fallback when clients are feeling overwhelmed.

For instance, you might encourage the client to notice the sensation of their feet on the ground or to rub their fingers together. This technique keeps clients anchored in the present, preventing dissociation by offering a safe physical reference point.

Gesturing involves mirroring a client’s soothing physical gestures, such as rubbing their arms or tapping. By reflecting on these motions, therapists help clients deepen their awareness of their body’s reactions and encourage a sense of safety and self-soothing.

For example, if a client is rubbing their arms, you might do the same and ask the client to notice any changes in their body as they repeat the motion. This shared nonverbal communication reinforces a sense of connection and control over the body’s response to stress.

The Help Now! strategy offers simple, practical exercises to redirect attention away from distress. These techniques—such as identifying objects by colour, counting steps, or pushing against a wall—work to decrease nervous system activation. Clients can use these exercises to manage their nervous systems outside the therapeutic setting, ensuring they stay within their resilience zone.

For example, when clients feel overwhelmed, you might ask them to count the colours they see in the room or describe nearby objects. These exercises distract the mind from distress and help the client return to a regulated state.

The Shifting and Staying skill helps clients consciously choose the best technique for them in moments of distress. Whether they engage in tracking, grounding, or a Help Now! strategy, the idea is to build mindfulness until emotional stabilisation occurs. Over time, with practice, these techniques become automatic responses, expanding the client’s resilience zone and allowing for greater emotional flexibility.

A vital goal of the Trauma Resilience Model is to promote neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to form new neural pathways. By consistently practising TRM skills, clients can transition from short-term cognitive strategies to long-term emotional stability.

Each skill in the TRM helps clients rewire their brains. For example, when clients repeatedly practice resourcing, they train their brains to shift from a default distress response to one of calm and safety. As they continue to employ these skills, the brain begins to lay down new neural tracks. This offers alternative pathways away from trauma-induced reactions like dissociation and distress.

Over time, the sympathetic nervous system no longer dominates the client’s responses to stress, and they can navigate difficult emotions with greater resilience.

In this way, TRM is about managing immediate distress and transforming the brain’s default pathways, enabling clients to sustain emotional regulation and well-being long after therapy ends.

The Trauma Resilience Model provides a robust, directive framework that empowers clients to self-regulate and maintain stability during therapy. By integrating these six skills into their practice, therapists can help clients develop long-term resilience, ensuring they are better equipped to manage trauma triggers and emotional challenges.

Incorporating TRM supports the healing process and enables clients to reclaim control over their emotional and physical responses, fostering a sense of safety and well-being. By expanding their resilience zone, clients can navigate life’s difficulties with increased confidence and stability.

Grabbe, L., & Miller-Karas, E. (2017). The Trauma Resiliency Model: A Bottom-Up Intervention for Trauma Psychotherapy. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 24(1), 76-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390317745133

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. Norton & Company.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. Norton & Company.

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us