Your Free Handout

Supporting Suicidal Clients

As a practising counsellor or psychotherapist, encountering a client with suicidal thoughts is not an if – it’s a when. Despite decades of clinical progress, suicide remains one of the most daunting and under-discussed aspects of therapeutic work. Whether you’re in training, newly qualified, or highly experienced, the fear of “getting it wrong” often looms large. Yet, with thoughtful preparation, reflective awareness, and evidence-informed strategies, you can create a therapeutic space where such conversations are not only possible, but potentially life-saving.

Supporting Suicidal Clients

Here are five key insights for enhancing your practice:

Ken Kelly: Working with suicidal clients.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yes. a delicate issue. But it is a conversation that has to be had because it’s something that therapists encounter. I think it’s one of the great fears that therapists have when somebody sits in front of them and says I think I want to take my own life. I don’t think that I’m useful to anybody anymore, and I just don’t see a future.

And how do we respond to that? I think preparation and understanding how to respond, doing some work before you actually get to the point where someone says they’re thinking of taking their own life is absolutely essential.

And suicidal ideation, it can range for fleeting considerations to detailed planning and many individuals have suicidal thoughts, but without acting on them.

But here’s the thing, Ken, all expressions of suicidality, which I think is a word, should be taken seriously.

Ken Kelly: Yeah. I couldn’t agree with you more, Rory. Sadly, I experienced a loss of a client during my time in practice. It wasn’t while I was working with them, but it impacted me deeply.

Every time I hear on the news or read in the paper of someone who takes their life, I think to myself, there’s someone who was not heard, somebody who potentially reached out, potentially spoke out to somebody and was not seen. And we as counsellors, psychotherapists, we are in the position where people may reach out, may speak up when working with us, and it’s an ethical and moral imperative, Rory, to understand this topic so that if we find ourselves in that situation, we already have an action plan. If a client should mention that they are considering taking their own life or feeling really worthless and can see no way out, that we are able to hold that person.

Not knee jerk and cause panic and call in a whole lot of other people unless it is required. And it’s about knowing the steps, knowing what to look out for, knowing how to hold a client, if we should find ourselves in that situation. And the topic we’re discussing today, we cover in a number of lectures in the Counsellor CPD Library. And I know today, Rory, you’ve particularly taken from Emma Chapman’s lecture on Working with Suicidal Clients. So definition, suicidal ideation, encompasses thoughts of ending one’s life ranging from fleeting considerations to detailed planning. So there is an arc there that we need to understand.

Many individuals may experience suicidal thoughts without acting on them, so there’s that side of it as well. But all expressions should be taken seriously, Rory.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, absolutely. And there’s a bit of a urban myth that does the rounds that people who talk about taking their own lives are the last people to do it.

And actually that’s not true at all. Any professional, be they a therapist or a medical professional should understand that. If someone expresses that they may think of ending their lives, it should be taken seriously. I think that it could be quite easy to practice defensive psychotherapy and withdraw from asking questions or being curious, because the therapists themselves may be fearful of getting it wrong or making it worse.

The fact of the matter is that if someone is determined to take their own life, or is thinking about it, what you say, what you inquire isn’t going to push them over the edge, if you like. So we should lean into it, we should ask, and also I think we should consider the risk elements.

So when we think about people taking their own lives, there are clear risk elements. So mental health conditions, things like depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, that can increase suicide risk, as can substance abuse or drug abuse. A majority of people who take their own lives are usually under the influence of either alcohol or drugs.

And also having a previous attempt, so a history of suicide attempts. So if someone’s tried to take their own life before, they’ve really crossed the boundary and that really does elevate risk. So those are kind of things to think about.

And also significant life events such as relationship breakdowns, financial hardship, bereavement and loss could contribute to it. So having those things in mind and having some sort of a plan with that information, you can make a sort of assessment in your mind about what the risk is. Is it likely to be low or is it likely to be high?

And that would inform you of what your next steps may be.

Ken Kelly: Yes and when we’re doing the initial assessment with a client, we’re asking, do you have any mental health disorders that you’re engaging with now or have previously?

These are standard questions and when we do that risk analysis before therapy, it’s there for a reason. So if we know what the high risk indicators are, and these high risk indicators come because of the research that is done. And one I’d like to add to that list is neurodivergence, specifically autism. There is a higher risk of someone who says that they are going to end their life if they’re neurodivergent, the risk is higher, the chances are significantly higher.

So knowing those risk factors, if we’ve identified risk factors, that wouldn’t necessarily be a knee-jerk reaction.It’s just that if they should give us the clues. And what we’re gonna do now is look at the warning signs. And warning signs, verbal clues, statements expressing hopelessness, worthlessness, or a desire to die.

And in some cases, the client may just say it as it is, I don’t want to be here anymore. I don’t wanna face these days anymore. I just want to end it all. They can be as blatant as that, but it can also be more veiled. I’m not worth anything to anybody, I just feel hopeless, might be an indicator.

So it’s watching out for those warning signs.

Behavioural changes, withdrawal from social activities, giving away possessions, sudden mood improvements after depression. Now that was an interesting one for me, Rory.Why would a sudden mood improvement be an indicator? And it may be, and this is my thoughts on this, it may be that person is going, I dunno how to deal with this, I can’t deal with this anymore, you know what? I think I’m gonna end my life, actually. Yes, that’s what I’m gonna do.

And suddenly it’s almost like a releasing of all that burden of having to carry it, because now I’ve got a solution, a sad solution. And then physical symptoms, changes in sleep patterns, appetite or personal hygiene.

Now, I’ll hand over to you for the assessment strategies of how we might delve a little deeper when we maybe see a warning sign.

And I just wanna say, if there is a warning sign without a risk factor, we still delve deeper. It doesn’t mean that if they don’t have a risk factor, we you know what, we’ll just pass that over, we’re gonna delve deeper anyway.

So assessment strategies, Rory.

Rory Lees-Oakes: When we come to assessment strategies, I think the best course of action is direct inquiry, ask open and non-judgemental questions about suicidal thoughts, plans, and means. And by doing that, if someone says to you, I just wanna end it all, and you say to them, okay I hear what you say, do you have any plan to do this? And they say, not really, I’m just having a bit of a bad day. The risk does lower a little bit.

But if they say yes, and then they give you a detailed plan of how to do it. That does put the risk up considerably. And determine whether the client has access to means.

So means could be things like, prescribed drugs or street drugs.Things like, I think about jumping off a bridge or something like that. So I think determine the immediacy of any plans. So in your conversation with a client, if the client says, I just don’t think I’m gonna be back for the next session, that means that there’s an immediate clear and present danger. And if they have access to the means to do it, or have told you the mechanisms of doing it, you’re really in a time-limited situation. You really have to think on your feet. The hopeful thing in this is that by speaking about it, they’re telling someone about it. Really open up the opportunity for dialogue for you to explore with the client. And, maybe just being heard is enough for them to put it on hold.

Now you can use assessment tools. There’s things like the back scale for suicidal ideation, But that comes with caveats, if you use any assessment tool, when you do a standardised assessment, doesn’t mean it’s written in stone. And, you couldn’t justify saying, the client, when I did the scale for suicide, it was low. If it comes up in a conversation, you should engage with it. And I think that, to be honest, it’s the scariest thing that a therapist can engage in really, because I think a lot of therapists might think that, the client’s behaviour, the client’s decisions are on them and they’re not. They’re absolutely not. Client makes decisions based on their own life.

You can only be there to help them, and depending on the contract, intervene.

Ken Kelly: Yeah. We have a responsibility to our clients, not for our clients. Their responsibility for their life is theirs. And, you covered direct inquiry, evaluation, intent and means and use of assessment tools there.

And for me, the most effective of those is that you are open and able to have the conversation. Client can only go as far as the therapist can go. If we’ve got a blockage or an area that we don’t feel comfortable going down, then we can’t be there with the client down that road.

So being okay to have the discussion being okay to say, what does that mean for you? You say, I don’t think I want to be around anymore, tell me more about what is that. And really going into that and being okay, nonjudgmental, kind and warm.

So if we feel that there is a high risk, first of all, just circle back to the contract that we shared with that client right at the beginning of our therapy.

It’s such an important document. Within your contract document, you’re going to mention that, confidentiality, that you would need to break that in the event that a person was thinking of harming themselves or another person.

So you might retouch on that gently before going into the intervention techniques, because if you do have to refer that client or hold that client while another service gets involved, you don’t want them to feel like you have betrayed them.

Intervention techniques is safety planning. What can we put in place and work with that person collaboratively to develop a plan that will include some coping strategies?

You could help them with emergency contact details that if they felt at the end of their tether, somebody that they might be able to reach out to. And that wouldn’t be you. Maybe the Samaritans or an another number depending on where you are in the world that person can reach out to.

And then enhance protective factors, strengthening the client’s support network, coping mechanisms. What recharges them? Who have they got around them? You can explore that.

And then of course there are times where we just have to refer. And certainly when I was in practice, my immediate referral pathway was through to the GP or doctor of the client. So it was one of the questions that I would ask in the intake is, who is your doctor?

But it is tricky the intervention techniques ’cause we don’t wanna be overly heavy handed. And this kinda started this saying, you don’t wanna have a knee jerk if somebody should bring this topic up.

Absolutely, Ken, and I think use of supervision is absolutely essential.

Rory Lees-Oakes: And I also think that understanding the demographic of age specific suicide rates is useful. So in England and Wales it’s males age 45 to 49 that are at the highest risk, and women age 50 to 54. So again, just having that in the back of your mind.

If you can show the client through unconditional positive regard and the relationship that they are important, that they are someone in the world, it may go a long way.

Ken Kelly: So true, that holding, non-judgmental space, unconditional positive regard is incredibly powerful.

And I guess it brings us onto ethical and legal considerations. We have confidentiality with encountering and psychotherapy. It’s the cornerstone, it’s what we build the practice on really. And there are limits to that confidentiality.

We must be covering that in our contracting and making the client aware of that right from the beginning so that there isn’t a feeling of betrayal.

And then duty of care, be aware of the legal obligations to protect your client.

If I came out of a heavy session with a client like that, I would be phoning my supervisor in between our supervision sessions and saying, can I speak to you? This is what’s going on.

And training. Do the CPD so that you are informed, so that you are there and prepared and able to support and help. Have all the referral services, the emergency services or numbers that you can hand over to a client when they find themself in that situation.

And have the knowledge to protect yourself by doing correct note taking, protect your practice by doing the right kind of things and evidencing the decisions that you are making. It’s a heavy topic, Rory, but it could not be more important.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, absolutely. And I think it does call for a lot of self care.

Ken Kelly: I think that those that feel worthless, unheard, unseen, we sit in a place of privilege. We could be that person that sees them, that hears them. That recognises where they are and wraps them in the unconditional love that we as therapists have. Shine that light into their life, put that hand into the darkness.

While formal suicide risk assessments like the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation can be helpful, they should not replace the nuanced understanding that comes from therapeutic dialogue.

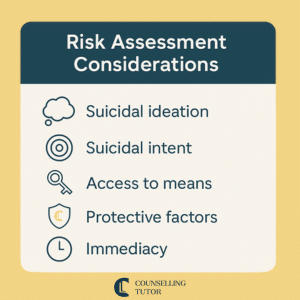

When assessing risk, consider:

Documenting these components and reviewing them regularly ensures clinical accountability and ethical clarity.

The term risk is often misunderstood in the counselling context. As Dr Andrew Reeves argues, risk is not binary (i.e. present or absent), but fluid and relational. All therapeutic encounters carry some level of risk, and a more useful framework involves positive risk-taking.

This involves:

Rather than viewing risk as a red flag to terminate or refer, many clients can be safely held within the therapeutic relationship, provided they have capacity and the risk is not immediate.

It’s important to distinguish between our responsibility to our clients and responsibility for our clients. We are not responsible for the client’s decisions. Still, we are responsible to them – to offer a non-judgemental space, ask the difficult questions, and respond with clinical integrity.

Risk is never static. A client might say they’re “fine” in session, but that doesn’t mean their circumstances or inner world can’t shift – sometimes rapidly. Risk must be seen as a dynamic, ongoing process. This means that even if we use tools like the PHQ-9 or conduct a thorough risk assessment at intake, our responsibility doesn’t end there.

As therapists, we need to stay attuned session by session: listening carefully, staying curious, and being willing to revisit risk whenever something feels different. It’s this sustained, relational vigilance that supports both safety and trust.

One of the strongest myths in suicide prevention is that discussing suicide might ‘plant the idea’. Research and practitioner experience alike affirm that asking about suicidal ideation often relieves distress. Counsellors must normalise and model open dialogue about suicide, which begins with confident, direct questioning such as:

“Have you had any thoughts of ending your life?”

When asked compassionately, this question communicates safety, presence, and a willingness to walk with the client through their distress.

The language we use when discussing suicide can either perpetuate stigma or reduce it. Avoid terms rooted in criminal or judgemental connotations, such as:

Instead, use neutral, compassionate alternatives:

Shifting our language can change the emotional atmosphere of the therapy room and make it safer for clients to disclose vulnerable feelings.

Supporting Suicidal Clients

Clients often avoid discussing suicidal thoughts due to complex emotional and social barriers.

These barriers can include:

Understanding these fears enables us, as therapists, to approach the topic more sensitively and effectively. It also reinforces the importance of clarifying the boundaries of confidentiality in the contracting stage and normalising the discussion of suicidal ideation from the outset.

As therapists, we may have our hesitations that interfere with broaching the subject of suicide, including:

Addressing these internal blocks through supervision and training is critical. The truth is, not asking is far riskier than asking. Talking openly about suicide has been shown to relieve distress, strengthen the therapeutic alliance, and create pathways for hope and safety planning.

When suicidal ideation is present, a well-crafted safety plan is a cornerstone of client care. A good safety plan should:

A bad safety plan, by contrast, can promote dependency, increase fear, and centre the therapist’s anxiety over the client’s needs. Importantly, these plans should be reviewed and adjusted regularly to remain relevant.

Suicidal ideation refers to thinking about, considering, or planning suicide. It can range from passive wishes (e.g. “I wish I wouldn’t wake up”) to more structured planning.

Suicidal intent, however, suggests a more concrete desire to act on those thoughts, potentially with a plan, means, or time frame. Distinguishing between ideation and intent is crucial for assessing immediate risk and determining intervention steps.

Therapists should always ask open questions to explore where the client sits on this spectrum.

Understanding the context around suicide risk can help therapists navigate assessment more effectively. Risk factors may include:

Conversely, protective factors include:

Warning signs may be subtle: giving away possessions, sudden mood lifts after depression, or expressions of hopelessness should all be taken seriously, even if veiled or ambiguous.

Clear organisational policy, informed consent, and ongoing supervision are essential. Be transparent with clients about the boundaries of confidentiality and your responsibilities around safeguarding. Also, acknowledge when your own history, bias, or emotional limits suggest referral might be more ethical than continued work.

Supervision plays a key role in managing the emotional toll and clinical decision-making when working with suicidal clients. Therapists may experience vicarious trauma, compassion fatigue, or feelings of impotence, especially following a client’s death.

Supporting clients experiencing suicidal ideation can carry a high emotional toll. Therapists may experience vicarious trauma, anxiety, or doubt about their professional competence, especially in the aftermath of a client suicide.

Self-care must be:

Neglecting self-care can lead to burnout or impaired therapeutic judgement. Staying resilient enables you to remain present and focused.

Recent data continues to highlight the complex landscape of suicide risk. A UK Government paper on suicide statistics (January 2025) reports that in 2023, suicide rates were highest among those aged 45 to 54, at around 16 per 100,000, and lowest for ages 14 to 19 with rates closer to 5 per 100,000.

The same report also notes that, statistically, men have a higher risk of suicide.

A May 2023 paper in the Primary Care Companion reports that suicide rates are 11–23% higher in spring and summer, with ED (Emergency Department) suicide attempts 1.2 to 1.7 times more common than in winter.

These trends may help us stay curious about how seasonal and demographic factors could shape client experiences.

Supporting Suicidal Clients

Suicidal ideation describes thinking about ending your own life, which may be vague or detailed, while suicidal intent means there is a clear decision to act, often with a plan, means, or set time in mind. Understanding this distinction helps therapists assess urgency and choose appropriate interventions.

No – asking compassionate, direct questions about suicidal thoughts does not create risk. In fact, it often reduces distress, builds trust, and opens the door to honest conversation and support planning.

Rather than treating risk as a yes-or-no issue, counsellors can view it as fluid and relational. This means openly discussing concerns, creating collaborative safety strategies, and revisiting risk regularly within a supportive therapeutic relationship.

There is no absolute formula for preventing suicide, and despite best efforts, loss may still occur. What matters is that you are equipped, present, and courageous enough to walk beside your clients in their darkest moments. By reframing risk, speaking openly, planning collaboratively, and maintaining your wellbeing, you offer clients not only support but a powerful, life-affirming presence.

This article is intended as a supportive resource for reflective practice. It does not replace formal training, supervision, or ongoing study in working with suicidal clients. Because of the complexity and gravity of suicide risk, we encourage all practitioners – whether in training or qualified – to seek out further CPD, ethical guidance, and supervision when working in this area. While no single resource can fully prepare you for this work, a commitment to ongoing development is a vital part of safe, compassionate practice.

Reeves, A. (2015). Working with Risk in Counselling and Psychotherapy. Sage.

Samaritans. (n.d.). Myths about Suicide

Chapman, E. (2020). Introduction to Suicide Awareness. CounsellingTutor.com

British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy. (n.d.). Counselling and Psychotherapy for Suicide Prevention – Systematic Review

House of Commons Library, Suicide statistics. Commons Library Research Briefing CBP‑7749, 8 January 2025. Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp‑7749/

Della, D. F., Allison, S., Bidargaddi, N., Chan, S. K. W. & Bastiampillai, T. (2023) An umbrella systematic review of seasonality in mood disorders and suicide risk: the Impact on demand for primary behavioral health care and acute psychiatric services. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord, 25 (3), article 22r03395.

Counselling Tutor provides trusted resources for counselling students and qualified practitioners. Our expert-led articles, study guides, and CPD resources are designed to support your growth, confidence, and professional development.

👉 Meet the team behind Counselling Tutor

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us