Your Free Handout

A Practical Guide to Donald Winnicott’s Attachment Theories

Attachment theory remains pivotal in psychotherapy and counselling. Donald Winnicott, one of the seminal contributors, has profound insights into early childhood development and the therapeutic relationship that continues to inform and enhance clinical practice. This article unpacks Winnicott’s attachment theories, offering practitioners a deeper understanding of how to apply these principles effectively in therapy.

A Practical Guide to Donald Winnicott’s Attachment Theories

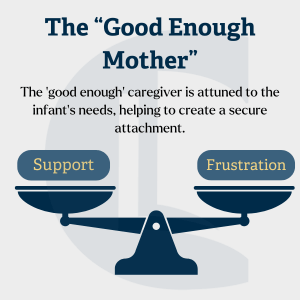

Central to Winnicott’s framework is the concept of the “Good Enough Mother,” which highlights the caregiver’s role in creating a secure attachment. The “good enough” caregiver is attuned to the infant’s needs, offering a balance of support and frustration, allowing the child to develop resilience. Winnicott emphasised the importance of holding – both physical and emotional – as foundational for a child’s emotional regulation.

Beyond the physical act of holding, Winnicott highlighted the importance of emotional holding – creating an environment where the infant feels secure and valued. This emotional holding provides a foundation for trust and resilience, allowing the infant to explore the world while knowing a secure base exists.

An essential element of the caregiver-child dynamic is the cycle of rupture and repair. When a caregiver fails to meet the infant’s needs momentarily – whether due to distraction or other factors – the subsequent act of repair, such as attending to the child with care and empathy, rebuilds trust and strengthens attachment.

We must be the “Good Enough Other” by providing an empathetic and consistent space, creating a secure base where clients can explore their emotions.

Recent research underscores the neurological impact of early attachment experiences, reinforcing Winnicott’s emphasis on the importance of holding and attunement. Studies, such as those examining Romanian orphans deprived of adequate caregiving, reveal that lack of consistent affection and connection can impair brain development, particularly in the frontal cortex. This highlights how early emotional security is not just psychologically but biologically foundational for a child’s growth.

For therapists, this reinforces the importance of creating a nurturing therapeutic space that encourages a sense of safety and connection. This underscores the counsellor’s role in compensating for early deficits. We offer a relational environment that supports the client’s capacity to heal and build emotional resilience.

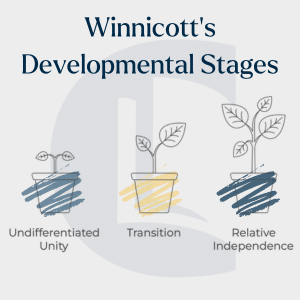

Winnicott identified three key stages in a child’s development:

Therapists can identify where clients may have experienced disruptions in these stages. They often manifest in attachment-related challenges in adulthood.

In the stage of ‘Undifferentiated Unity,’ the child perceives an illusion of control over their caregiver, creating omnipotence. During ‘Transition,’ the child experiences disillusionment, recognising that others’ needs may sometimes come before their own. If managed appropriately by the caregiver, this frustration lays the groundwork for a healthy sense of independence. Finally, ‘Relative Independence’ allows the child to internalise the caregiver’s presence and regulate themselves.

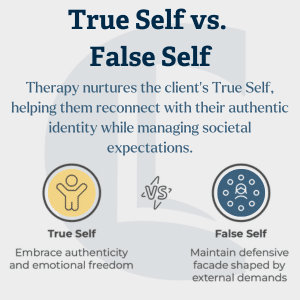

Winnicott distinguished between the True Self, which represents authenticity and emotional freedom, and the False Self, which is a defensive facade shaped by external demands. A securely attached individual transitions naturally between these states. However, early emotional neglect can result in a maladaptive False Self, often observed in clients with borderline personality traits.

Winnicott’s views are deeply connected to object relations theory, which explores how early relationships with caregivers influence our inner sense of self and how we relate to others. This is often observed in therapy through transference dynamics, where clients project unresolved emotions and relational patterns onto the therapist. By holding these projections empathetically and without judgement, counsellors and psychotherapists provide clients with a corrective emotional experience. This enables the integration of past relational wounds and the development of a more cohesive sense of self.

Therapy nurtures the client’s True Self, helping them reconnect with their authentic identity while managing societal expectations.

Therapists should pay close attention to the client’s emotional age, which may not align with their chronological age. A client who appears emotionally younger might require responses akin to those given to a child, including reassurance, patience, and clear boundary-setting, to encourage the growth of their True Self.

Winnicott introduced the idea of transitional objects – comfort items like blankets or teddy bears – that help children manage separation anxiety and encourage independence. In therapy, symbolic transitional objects can offer clients emotional regulation between sessions.

Counsellors might also introduce transitional objects during particularly challenging phases of therapy. For example, offering a symbolic item like a smooth stone or bracelet could remind the client of the therapeutic relationship and reinforce the client’s ability to self-regulate and maintain connection during periods of distress.

While groundbreaking, Winnicott’s attachment theories are not without critique. His work focused predominantly on child development and lacked empirical data, relying heavily on qualitative observation. Moreover, his Eurocentric perspective may not fully account for diverse cultural parenting practices.

Consider how caregiving norms vary widely – what is considered ‘Good Enough’ in one culture may differ in another, requiring therapists to adapt these principles to each client’s cultural and familial context.

Another notable limitation is the lack of quantitative research to substantiate Winnicott’s observations. While his theories are insightful, he drew them mainly from his clinical experiences. They may not be universally applicable, particularly across cultures where caregiving practices and family dynamics differ significantly from those assumed in his work.

Integrating Winnicott’s ideas requires contextual sensitivity. Consider how his concepts, such as holding and transitional objects, can adapt to the client’s cultural and personal background.

Winnicott’s “Good Enough Mother” is a caregiver who offers attuned, but imperfect, responses – allowing manageable frustration so the child builds resilience and a separate sense of self. In therapy, being the “Good Enough Other” creates a secure base for clients to feel safe enough to explore and heal.

The True Self emerges from spontaneity and responsive caregiving, while the False Self is a protective facade shaped by unmet emotional needs. In counselling, nurturing the True Self helps clients reconnect with authenticity, while understanding the False Self offers insight into defensive relational patterns.

Transitional objects – like a blanket or toy – symbolise the child’s growing awareness of being separate from the caregiver and support emotional comfort during separation. In therapy, introducing a symbolic transitional object (e.g. a journal or token) can help clients sustain emotional regulation and connection between sessions.

A Practical Guide to Donald Winnicott’s Attachment Theories

Donald Winnicott’s theories provide profound insights into the intricate dynamics of attachment and identity formation. His concepts, such as the Good Enough Mother, True and False Selves, and transitional objects, illuminate the critical role of attunement and emotional holding in nurturing growth and healing. These ideas highlight the importance of creating a therapeutic environment that mirrors the safety and empathy foundational to secure attachments.

By integrating Winnicott’s principles into practice, counsellors and psychotherapists can better support clients in reconnecting with their True Self, addressing disruptions in developmental milestones, and building resilience for healthier, more authentic relationships. Much like the caregiver-child dynamic, the therapeutic relationship thrives on consistent emotional holding and the ability to repair ruptures, reinforcing trust and promoting deeper healing.

As you reflect on these theories, consider how they align with your practice. Can you cultivate a space where clients feel held and seen, empowering them to explore their True Self? Can transitional objects or empathic boundaries enhance their journey? Winnicott’s legacy invites us to step into the role of the Good Enough Other, championing authenticity and resilience in the lives of those we support.

Gerhardt, S. (2004). Why Love Matters: How Affection Shapes a Baby’s Brain.

Winnicott, D.W. (1965). The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment.

Counselling Tutor provides trusted resources for counselling students and qualified practitioners. Our expert-led articles, study guides, and CPD resources are designed to support your growth, confidence, and professional development.

👉 Meet the team behind Counselling Tutor

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us