Your Free Handout

Applying Neuroscience in Counselling

Neuroscience has rapidly evolved in recent decades, offering huge insights into human behaviour, cognition, and emotional regulation. For counsellors and psychotherapists, integrating neuroscience into practice enhances our understanding of how the nervous system influences client experiences, particularly in response to trauma, safety, and relational dynamics.

This perspective is informed by the work of Maggi McAllister-MacGregor, a therapist with over 20 years of experience in the NHS and private practice. Her background in bodywork and early academic interest in neuroscience have shaped her approach to therapy. Noticing clients’ emotional responses during bodywork sessions led her to explore the mind-body connection further, eventually integrating neuroscience into her counselling practice.

This article explores key neuroscience principles relevant to counselling and how they can be practically applied to improve therapeutic outcomes.

Applying Neuroscience in Counselling

By the end of this article, you will:

Neuroscience is an interdisciplinary field that extends beyond psychology and biology, encompassing mathematics, linguistics, engineering, computer science, and philosophy. Some neuroscientists study cellular processes, while others examine the nervous system’s influence on behaviour.

Interpersonal neurobiology is a key area relevant to therapy. It explores how nervous systems interact and regulate each other, a concept central to therapeutic relationships.

At its core, the nervous system is a continuous flow of energy and information, processing sensory input from external and internal environments. This processing dictates physiological, emotional, and cognitive responses. As therapists, we recognise that many client behaviours are shaped by nervous system activity, allowing us to reframe responses such as anxiety, avoidance, or hyperarousal as survival mechanisms rather than personal failures.

Dan Siegel’s concept of “name it to tame it” illustrates how verbalising an experience can engage the prefrontal cortex, reducing the activation of lower brain structures responsible for defensive responses. This knowledge helps therapists guide clients towards self-regulation and greater control over their reactions.

A practical example of this process can be seen in how individuals respond to fear. For example, if someone has a fear of spiders. As a teenager, encountering a spider triggered an immediate fight-or-flight response, leading to panic and accidental injury of self. Decades later, faced with a similar situation, the individual consciously engaged their prefrontal cortex by naming their fear and instructing themselves to “just flick it off.” This simple cognitive process allowed them to remain regulated, demonstrating how understanding the brain’s role in emotional responses can empower clients to manage their reactions more effectively.

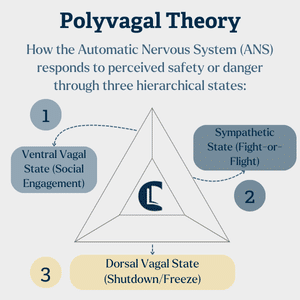

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) comprises the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, responsible for mobilising or calming the body. The polyvagal theory, developed by Stephen Porges, provides a framework for understanding how the ANS responds to perceived safety or danger through three hierarchical states:

These states influence not only emotional well-being but also relational dynamics. Clients with trauma histories may struggle to access social engagement states, remaining stuck in defensive responses. By creating safety in the therapeutic space, counsellors can help shift nervous system responses towards regulation.

Trauma can alter the nervous system’s threshold for detecting threats, making individuals more likely to perceive neutral or even positive situations as dangerous. This results in hypervigilance, increased pessimism, and a tendency to expect negative outcomes—a survival-driven bias known as the “negativity bias.” Neuroscientist Rick Hanson describes this as the brain having “Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positive ones,” meaning distressing experiences are more likely to stick, while positive ones are easily dismissed. Understanding this can help clients reframe their responses as natural adaptations rather than personal shortcomings.

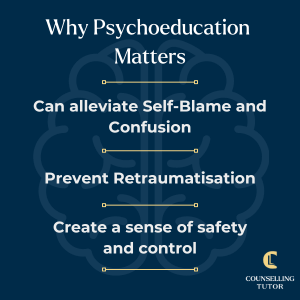

Trauma fundamentally alters how the nervous system interprets and responds to the world. A key impact of trauma is the dysregulation of the nervous system, leading to hypervigilance or dissociation. Understanding that trauma-related responses are biologically driven rather than conscious choices can reduce client self-blame and shame.

For example, many trauma survivors experience “freeze” responses in threatening situations, later feeling guilt for not reacting differently. Educating clients on the nervous system’s automatic defence mechanisms can create self-compassion and aid in healing.

Additionally, trauma disrupts the ability to engage in co-regulation—where one nervous system influences another, as in caregiver-child interactions. In therapy, the therapeutic relationship can act as a form of co-regulation, helping clients experience emotional safety and stability.

One of the most effective ways to integrate neuroscience into therapy is through psychoeducation. Helping clients understand their nervous system’s role in their experiences can provide relief and increase self-awareness.

This can involve:

Therapists must be aware of their nervous system states, as they can regulate or dysregulate clients. Practising self-regulation techniques – such as breathwork, mindfulness, or grounding exercises – ensures therapists maintain a calm and engaged presence. This, in turn, creates a therapeutic environment that promotes client safety and connection.

Before individuals learn to self-regulate, they rely on external regulation—first from caregivers and later from relationships and therapeutic interactions. In infancy, caregivers attune to a child’s nervous system, helping to bring them back to a state of balance when distressed. This experience forms the foundation for emotional self-regulation in adulthood. However, when early relationships fail to provide this regulation, individuals may struggle with emotional balance later in life.

In therapy, the therapist serves as an external regulator, offering cues of safety and stability that help the client experience regulation. This process is essential, as nervous systems do not operate in isolation but continuously influence one another.

Since trauma is stored in the body, integrating somatic techniques can be highly beneficial. Approaches such as Sensorimotor Psychotherapy (Pat Ogden) and Polyvagal-informed interventions emphasise bodily awareness as a means of accessing and regulating emotional experiences.

Therapists can incorporate:

Neuroscience has demonstrated the brain’s ability to rewire itself through neuroplasticity. By repeatedly engaging in regulated, positive emotional states, clients can reshape neural pathways associated with stress and trauma. Practical strategies include:

Applying Neuroscience in Counselling

Neuroscience helps counsellors understand how the nervous system shapes thoughts, feelings and behaviours, allowing them to reframe client responses (like anxiety) as survival mechanisms rather than personal failures and tailor interventions more effectively.

The autonomic nervous system, including the polyvagal states of safety, fight‑flight and shutdown, explains how clients’ bodies respond to perceived threat or safety, helping counsellors create therapeutic spaces that promote regulation and social engagement.

Counsellors can use psychoeducation about nervous system responses, grounding practices, emotional labelling and somatic awareness to support client self‑regulation, reduce self‑blame and encourage positive neural change.

Understanding and applying neuroscience in counselling practice enhances our ability to support clients meaningfully. By recognising the nervous system’s role in shaping emotions, behaviours, and relationships, therapists can encourage greater self-awareness, self-compassion, and healing in their clients.

As our knowledge of neuroscience expands, so will the opportunities for developing more effective, evidence-based therapeutic interventions. By integrating these insights into practice, counsellors can contribute to the evolving landscape of trauma-informed care, ultimately improving client outcomes and well-being.

Dana, D., 2018. The polyvagal theory in therapy: Engaging the rhythm of regulation. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Fisher, J., 2017. Healing the fragmented selves of trauma survivors: Overcoming internal self-alienation. New York: Routledge.

Ogden, P. and Fisher, J., 2015. Sensorimotor psychotherapy: Interventions for trauma and attachment. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Ogden, P., Minton, K. and Pain, C., 2006. Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S.W., 2011. The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

van der Kolk, B., 2014. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Viking.

Counselling Tutor provides trusted resources for counselling students and qualified practitioners. Our expert-led articles, study guides, and CPD resources are designed to support your growth, confidence, and professional development.

👉 Meet the team behind Counselling Tutor

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us