Your Free Handout

Practical Tips for Counsellors Working with Loss and Bereavement

Counsellors and psychotherapists working with grief must navigate a complex web of emotions, behaviours, and individual histories. Loss and bereavement are universal experiences but manifest uniquely in every client. Drawing on principles from attachment theory, grief models, and clinical practice, this guide provides actionable insights for practitioners.

Practical Tips for Counsellors Working with Loss and Bereavement

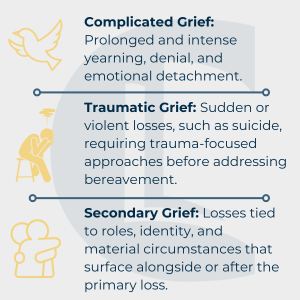

Grief is not a singular experience but encompasses varied forms, including normal, complicated, and traumatic grief. These presentations are influenced by a client’s attachment style, previous experiences, and the circumstances of the loss. Recognising these variations helps tailor therapeutic interventions to meet individual needs.

Cultural norms shape grief expressions. Practitioners should sensitively inquire about and honour clients’ cultural mourning practices to ensure their approach aligns with these values.

John Bowlby introduced attachment theory, which is foundational to understanding grief. Early attachment patterns influence how clients experience and process loss.

Practical Application: Explore a client’s attachment history to identify potential barriers to healthy grieving.

Research links complicated grief to attachment-related risk factors, including weak parental bonding, childhood separation anxiety, and adverse reactions to change. Exploring these factors can help practitioners understand the root of the client’s grief and develop tailored interventions.

Pathological attachment patterns, such as anxious dependency or compulsive self-reliance, often result in maladaptive grief responses. Addressing these patterns during therapy can improve emotional processing and integration.

Chronic grief often affects individuals who are compulsive caregivers. These individuals have a strong need to care for others, often at the expense of their own needs. Their grief may focus on the loss of their caregiving role rather than the deceased. Exploring how this role shaped their identity can help reconstruct their sense of self post-loss.

Complicated grief presents as being “stuck” between processing the loss and moving forward. Indicators include extreme anger, denial, or conspiracy theories about the loss.

Clients experiencing complicated grief may present with somatic symptoms that reflect the deceased’s illness, such as headaches or stomach pains. Recognising these symptoms as grief-related and exploring their connection to the loss can provide valuable therapeutic insights.

Sudden, unexpected losses can induce trauma, impairing a client’s ability to engage in grief work.

Preparation for death, such as during prolonged illness, may mitigate trauma and provide opportunities for closure. In contrast, sudden losses often leave clients grappling with shock and unresolved emotions, requiring trauma-first interventions to stabilise the client before processing grief.

Practitioners should be mindful of triggers and flashbacks that may arise, especially in cases of traumatic grief. Techniques such as grounding exercises and mindfulness can help clients manage these responses.

Clients may focus on losses related to roles, financial stability, or future plans rather than the deceased. For instance, a widow may struggle with the practicalities of selling a house, a role previously shared with the deceased. These secondary losses can significantly impact the grieving process and should be addressed in therapy.

Secondary grief often acts as a buffer, with clients focusing on practical or material losses first. Practitioners should allow these concerns to unfold organically, as resolving secondary grief creates a foundation for exploring the emotional core of the primary loss.

Grief often intersects with existential concerns, such as loss of purpose or identity. Therapists can help clients explore these themes and create a renewed sense of meaning post-loss.

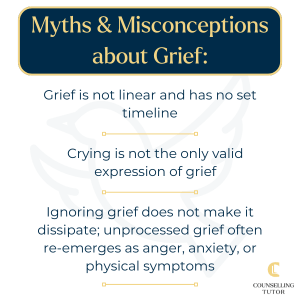

Dispel misconceptions to normalise diverse grieving processes:

Help clients recognise that grief is deeply personal and not confined to timelines or stereotypes. Normalise diverse grief responses and encourage clients to engage with their unique process without judgement or comparison. This understanding and empathy are crucial in providing practical support.

Counsellors should be able to distinguish between normal, complicated (or prolonged), traumatic, and secondary grief, as each demands different approaches. Normal grief evolves, complicated grief features intense persistence, traumatic grief may need trauma‑first interventions, and secondary grief involves losses of roles or identity rather than the person.

Referral is advised when grief presents psychotic symptoms, persistent denial of loss, or somatic symptoms mirroring the deceased’s illness – for example, migraines linked to a partner’s brain tumour – as these signal complications beyond the scope of routine bereavement counselling.

Attachment patterns shape grief responses: anxious attachment may cause chronic yearning or dependency, avoidant attachment can delay grieving, and compulsive self-reliance may obscure emotion for years. Exploring a client’s attachment history helps tailor interventions to support healthy integration of loss.

Practical Tips for Counsellors Working with Loss and Bereavement

Grief work is as varied as the clients who experience it. Counsellors and psychotherapists can offer empathetic and practical support by incorporating attachment insights, recognising complex presentations, and aligning interventions with client needs. Embracing the complexity of grief is essential in providing comprehensive and effective care.

Remaining attuned to when additional help or referrals are required ensures clients receive the best care for their unique journey through loss.

Practitioners are encouraged to engage in self-care, access supervision, and recognise their own grief triggers. Self-awareness and responsibility are key to maintaining professional boundaries and providing effective care.

Barkway, P. Psychology for Health Professionals.

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and Loss.

Prigerson, H., & Ray, W. (2006). Complicated Grief as an Attachment Disorder.

Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement.

Counselling Tutor provides trusted resources for counselling students and qualified practitioners. Our expert-led articles, study guides, and CPD resources are designed to support your growth, confidence, and professional development.

👉 Meet the team behind Counselling Tutor

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us