Autism-Informed Practice Course

Gain the Knowledge & Skills to Support Autistic Clients with Confidence & Compassion

The following article is taken from our Autism-Informed Practice course.

Gain the Knowledge & Skills to Support Autistic Clients with Confidence & Compassion

The contribution that autistic individuals make to society is remarkable, but it’s essential to recognise the unique challenges they may face. For counsellors and psychotherapists, understanding autism strengths and challenges can enhance therapeutic outcomes when working with autistic clients.

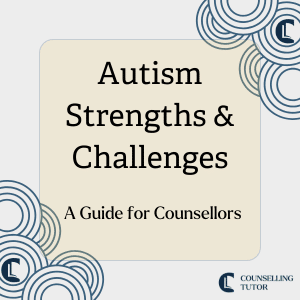

Autistic individuals sometimes exhibit exceptional skills in attention to detail, visual perception, and specialised knowledge. However, they may also face difficulties in communication and energy management, requiring specific approaches from practitioners to support them effectively.

Autism Strengths and Challenges

By engaging with this article, practitioners will:

Ken Kelly: We’re speaking about autism strengths and challenges. Why would we put strengths and challenges together with autism?

Rory Lees-Oakes: I think that it’s quite widely understood now that those people who are autistic may find some tasks easy to do, and some areas of life a bit of a struggle.

Dr. Steven Shaw, the professor of special education at Adelphi university in the USA, who has written a lot about this, states that just like the rest of humanity, autism is an extension of the diversity found in the human. Some autistic people may have challenges in communication or social interaction.

Every autistic person is different. Once you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person. Autistic people like the rest of humanity are very different. However, there are some strengths we may see in autism.

We’re not meeting a set of diagnosis or a stereotypical view of who they are.

What we need to do is find out who they are first. And that takes a little bit of time through the arc of therapy, and then we work around the idiosyncrasies of who they are in and the fact that they are neurodivergent.

Ken Kelly: Beautiful intro to that, Rory. Yes, and yes again. Maybe you as a counsellor, psychotherapist, you’re looking to welcome neurodivergent clients into your therapy room and this is important for us to discuss and understand.

As you said, Rory, if we look at the entirety of humanity, everybody has strengths and challenges. We all do. It’s just part of being human. There’ll be things that you’re good at and things that maybe you’re not so good at. When we look to the research specifically within autism, there are certain traits that are more common. This does not mean that these are the traits that everybody that is autistic has. They are just more commonly occurring in an autistic individual,

and you touched on one of them, which may be challenges interacting socially. That doesn’t mean that every autistic person has these challenges Some autistic people love interacting and being social. Generally, If you look across the autistic community, there will be a higher incident of communication challenges.

Understanding where a person’s strengths and challenges lies, in general, is useful in therapy.

If we are welcoming a neurodivergent person into our therapy room, understanding where they see their own strengths and their own challenges can really be helpful. And this goes into other neurodivergence as well.

More challenges might be that the autistic individual may be sensitive to light. They may be sensitive to certain noises. They may be sensitive to certain perfumes or smells within the therapy room. And of course we can make reasonable adjustments if we understand what they are to accommodate that.

So if the person is really sensitive to light and you’ve got a chair that faces an open window, you might close the curtains for that person if they have given you that information. They will give you that information if you ask for it in a respectful way. And I guess the opposite of challenges, because I’ve focused on a few here, is that everybody has strengths and that’s no different with autistic people.

They will have their strength areas. One strength that is pretty common amongst autistic people is having a special interest in a certain area. I certainly have special interests. Rory, I know you’ve got special interests.

And if you understand what somebody’s strengths are, you can key into that as well. If the person may present in therapy, you can see their energies are very low, they’re not showing up as they normally show up, chances are they’ve had an interaction or something has happened that day that has depleted their energy. If you know what their strengths are, you can talk about those.

You can lean towards those. For example, if the person has a special interest in a certain area, you might ask them how that’s going it may energise them, and bring a little bit of a spark back into how they are within the room. So that’s a very brief overview of why it’s important that we understand those strengths and challenges, Rory.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yes, I think it’s fair to say that I identify that. I could talk all day about certain subjects, and I’ve now learned that these are very interesting to me,

they may have limited interest to other people. I think one of the things we should touch on is relationships.

I think that one of the things that I’ve noticed in myself, and other autistic people, is that they tend to be very loyal and very honest and deceptions or people not being truthful can be quite hurtful.

And I don’t think it’d be the first time that I’ve seen someone in my therapy room who is neurodivergent, who’d felt very let down by people because they’d come to the relationship being very honest and very loyal. And sometimes that is very difficult to realise that not everybody else is like that.

So that’s something that you might have presented in the therapy room, and I think it’s really useful. As therapists, we tend to be as honest as we can be.

I think for autistic people, conditions of worth and interjected values, are a big thing.

And I think we need to keep that tuned into our minds when we’re working with neurodivergent people, because of how the world treats them.

Seeing people as people first and then working with whatever they bring. It might be that it’s the little things like eye contact.

Not every autistic person wants eye contact. I was speaking to a colleague of mine who works with an autistic child, or a child who is autistic, and they put the chairs back to back. So they don’t have to look at each other.

So I think an aspect of creativity and aspects of inquiry is really important, and where we can, making those reasonable adjustments, even if they feel a little bit different from us.

Sometimes our frame of reference, we have to put to one side to make sure that the person in front of us is being best served.

Ken Kelly: Yeah and I agree that there is more information than has been around in recent years. I think that the internet and social media is helping, because an autistic individual or a neurodivergent individual can claim them.

I am autistic. And I think welcoming neurodivergence into our counselling rooms. The truth is, if you look to the statistics of the population, chances are you’ve had neurodivergent clients before.

What is different? We can see how we can better serve by having the conversation, We can ask different questions, we can ask what kind of challenges do you face, and how can we work on that here within the room?

How do you prefer to sit? How is eye contact for you? Is that uncomfortable for you? And you can feel that out and an autistic person is not going to feel that those are invasive questions. These are the challenges that this person may face on a daily basis. It is refreshing to have somebody ask and care about that.

And we’re spending time on challenges here. I’m going to go back to school, Rory, with my challenge with the spelling. Therefore in English, I really struggled. However, I was really good at standing up and speaking.

There you go. There’s a strength, and a challenge. I guess a reasonable adjustment, is that instead of writing and putting an answer in, a reasonable adjustment could have been that they would read the question to me and ask me to verbally answer it and then have somebody fill that in. That did not exist in my day.

I know it does today, and that is great to see, there is how a strength can offset a challenge just by asking a question and knowing that it exists.

Rory Lees-Oakes: The more we educate ourselves, the more inclusive we can be as counsellors and psychotherapists. Absolutely. And we shouldn’t leave any client behind, where possible we should always offer service, which includes everybody where we can.

And I think that’s really important. We’re really only at the beginning, I think, of engaging with neurodivergence and understanding its nuances and how it presents in people. Now it’s being seen and spoken about and the language is being developed.

I guess we’re living in a time where being autistic or being neurodivergent is seen as another facet of humanity. And I’m sure in the future that will develop. But yeah, have you got anybody who may show traits of autism? Are you making reasonable adjustments? Has anybody said, I fidget a lot, just some things that people can fidget with.

You don’t have to promote them, just have them on the table. So there’s lots of areas where we can really support neurodivergent individuals. And rightly, because it’s another aspect of diversity. And as a therapist, we strive to work with diversity to understand diversity in all its forms, Ken.

Ken Kelly: Definitely, it would be unthinkable if you had a person that was wheelchair bound, got to your therapy room and you had stairs in your therapy room and you had not mentioned this or made this apparent beforehand.

And the person said, I need assistance getting up the stairs. If we then said that’s your problem, you should be able to make your way up the stairs. That is unthinkable. We can see that is unethical. Nobody would even think of acting in that way.

However, we can inadvertently discriminate, I guess, by not understanding if we’re working with a neurodivergent person and they have challenges that we are unaware of, we are inadvertently doing the same kind of thing with discriminating. It might feel a little bit uncomfortable as the counsellor to close your curtains because the light is too intense for that client.

We’d have to ask to know that first, or maybe we might see that discomfort within them, but we make those allowances. Why? Because it is the right thing to do and asking and understanding is the right thing to do. We focused a lot on the challenges here, but the strengths are interesting as well and it’s been mentioned, but there is no one size fits all, everybody is an individual, every neurodivergent individual is individual.

I don’t want a stereotype. It’s not that everybody is a rain man, everybody is a savant, everybody can play a musical instrument from the age of three. Yes, that does exist, but it is not common.

I think that what we need to do is take the standard stereotypical counselling hour and everything within it. Any of those is up for adaption. You may get a client who says I could only do half an hour today. Yes.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Only do half an hour. That’s fine. Or any chance the next session I could do one and a half hours? You might think, but it’s an hour, isn’t it? Counselling is an hour. I don’t think we need to be too dogmatic when we’re working with the panoply of humanity. Maybe you go, all right then, one and a half hours, if this is your work and you charge, you may have to alter the fee.

Be creative, within the space.It may not sound like therapy per se, but for that person to be able to talk about, I don’t know, I’ll talk about one of my special interests, resident frequencies of antennas, they may not be able to speak about that to anybody else.

They may not have anybody else who is willing to listen to that. And this comes again back to Rogers, just to have someone who listens, and who takes the time to understand, that gives that space, is therapy.

It is therapy. And I think that as we go forward, therapists are going to recreate the therapeutic environment to fit neurodivergent people better.

Ken Kelly: Yes, you’ve said, I think, the key point here.

We can read the books, we can read the research papers, we can have an understanding of neurodivergence, we can understand autism, we can understand how people might present. At the end of the day, how do you transfer that into your practice?

How do you make the reasonable adjustments in your therapy? I think that is the key here.

Recognising the need to do the CPD. Not only is it the right thing to do, we’re legally bound, specifically here in the UK, to be open and to make reasonable adjustments where they are required, for any type of otherness.

Autism presents a diverse array of strengths and challenges. While many people on the spectrum may excel in specific domains, their individual experiences of autism can vary dramatically. This section explores the key strengths and challenges and offers guidance on how therapists can adapt their approaches to meet the needs of autistic clients.

Autistic individuals often demonstrate unique strengths that can be leveraged in therapeutic work. These include:

Recognising these strengths allows practitioners to empower their clients by focusing on capabilities rather than their deficits in therapy.

While autism is associated with unique strengths, individuals on the spectrum may encounter various challenges, particularly in areas related to social interaction, communication, and managing sensory input. Common challenges include:

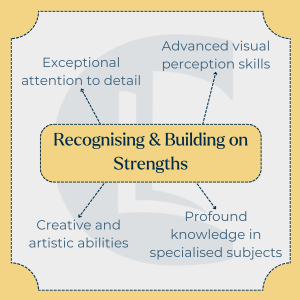

The Spoon Theory, introduced by disability advocate Christine Miserandino, offers a helpful metaphor for understanding how autistic clients manage energy. Each task throughout the day can deplete a limited amount of energy, represented as “spoons.” For autistic individuals, seemingly simple tasks like social interactions or attending appointments can be particularly draining.

Understanding energy management can guide practitioners to make necessary adjustments in therapy, such as shortening sessions or rescheduling them when the client has more energy. This approach emphasises flexibility and responsiveness to the client’s needs, ensuring that therapy remains effective without overwhelming the individual.

Making reasonable adjustments is essential to providing person-centred care that responds to each individual’s unique needs and preferences when working therapeutically with autistic clients. These adjustments are practical changes that a therapist can make to ensure that therapy is accessible and valuable for autistic individuals, recognising that autistic people may process information differently or experience communication and sensory sensitivity challenges.

Here are some examples of reasonable adjustments that you can incorporate into your practice:

Some autistic clients may struggle with verbal communication or prefer non-verbal communication. Therapists can accommodate this using written prompts, drawing, or visual aids. Non-verbal clients should consider using assistive technology that allows them to express their thoughts through alternative methods like typing.

Many autistic individuals are sensitive to sensory input such as bright lights, loud noises, or strong smells. In a therapy setting, therapists can make adjustments by dimming lights, ensuring quiet environments, and asking clients about any sensory triggers they may have. Small changes like this can significantly affect the client’s comfort and ability to engage in therapy.

Therapy can be taxing for autistic clients, particularly in sessions that require a lot of focus or social interaction. Offering regular breaks during longer sessions can help clients recharge and avoid burnout. This is especially relevant in masking, where clients might be expending additional energy to conform to social expectations.

Autistic individuals often have intense interests in specific subjects. Therapists can incorporate these interests into sessions to engage clients more deeply. This helps build rapport and creates a more comfortable and familiar space for the client to explore complex topics.

For some autistic clients, attending therapy in person can be overwhelming due to the challenges of travel or sensory sensitivity. Online sessions may alleviate this stress, allowing clients to engage in therapy from a familiar and controlled environment.

Some autistic clients might find it helpful to have a trusted family member or support worker attend therapy sessions. This can provide additional emotional support or assist in communication, helping the therapist better understand the client’s needs.

Making these adjustments demonstrates a therapist’s commitment to inclusivity and ensures that therapy is accessible to clients regardless of their neurodivergent characteristics. Customising therapy in this way is not only beneficial for the client but also deepens the therapist’s ability to meet the needs of autistic individuals effectively.

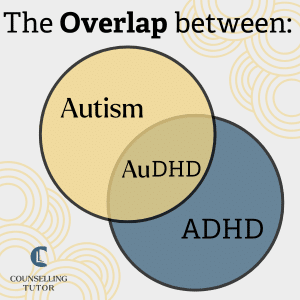

The overlap between autism and ADHD has become more widely acknowledged, with research showing that these conditions frequently co-occur. The term AuDHD describes individuals who are both autistic and have ADHD. This differential diagnosis presents its complexities, as the traits associated with each condition can interact in various ways.

Practitioners must be attuned to this interplay and adapt their approaches accordingly. Since 2013, diagnostic criteria have evolved to recognise this overlap, enabling a more nuanced understanding of neurodivergence in therapy.

Autism Strengths and Challenges – A Guide for Counsellors

As a counsellor or psychotherapist, working with autistic clients requires a flexible, client-centred approach that embraces the diversity within neurodivergent experiences. The unique strengths and challenges faced by autistic individuals offer an opportunity for you to tailor your practice to support their individual needs.

By recognising and incorporating their strengths, such as attention to detail and advanced visual or creative skills, you can engage clients more effectively and build trust in the therapeutic relationship. At the same time, understanding and addressing the challenges they face—particularly with energy management and communication—allows you to create a therapeutic environment that is both supportive and responsive. Spoon Theory offers a valuable framework for this, helping you better understand how autistic clients may experience and manage their energy levels throughout the day.

Making reasonable adjustments in your practice is not just a legal or ethical responsibility—it is key to enhancing therapeutic outcomes. Whether offering flexible session times, adjusting communication methods, or managing sensory sensitivities, these accommodations can make therapy more accessible and practical for autistic clients. Moreover, staying open to continuous learning, especially about co-occurring conditions like AuDHD, ensures you are well-equipped to handle the complexities of neurodivergence.

Ultimately, your ability to adapt and individualise your approach is crucial. Every autistic client is unique, and by stepping beyond your frame of reference, you can provide personalised care that truly addresses their needs. Regularly reflect on how your understanding of autism is evolving, and seek supervision or further training if needed. This commitment to ongoing professional development will enhance your practice and contribute to a more inclusive and empathetic therapeutic community.

It’s always worth remembering that when you meet one autistic person, you’ve only met one autistic person. Just as with any client, each individual is unique, with their own frame of reference and experiences.

Autism Epicenter. (n.d.). Autism Poems & Creative Works. Available at: Autism Epicenter

Boyle, S. (2024). The sudden rise of AuDHD. The Guardian. Available at: The Guardian

International Board of Credentialing and Continuing Education Standards (IBCCES). (2018). Interview with Dr. Stephen Shore. Available at: IBCCES Blog

McCann, L. (2021). Spoon Theory & Autism. Available at: EdPsychEd

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us