Trauma Informed Practice Course

The Competence and Confidence to Work with Trauma in Your Practice.

The following article is taken from our Trauma-Informed Practice course.

The Competence and Confidence to Work with Trauma in Your Practice.

The human brain’s response to trauma is a vital area of study for counsellors and psychotherapists, especially if you’re practising within a trauma-informed framework. This article offers an overview of brain function, mainly how it operates during traumatic situations. Drawing on historical and contemporary insights, the discussion covers the brain’s structure, the roles of different brain regions, and the physiological responses to perceived danger.

Before developing psychoanalytical therapy, Sigmund Freud, a pioneering neurologist, contributed significantly to our understanding of neurobiology. His work in the late 19th century laid the groundwork for studying trauma-related brain functions. Freud’s research, particularly in the biology of nervous tissue, highlighted the importance of understanding the brain’s physical structures, an endeavour that continues to inform trauma-informed practices today.

Overview of Brain Function: Key Insights for Trauma-Informed Practice

Understanding how the brain is structured is crucial for grasping its response to trauma. This article offers an uncomplicated explanation of the brain and its functions during trauma that can assist counsellors in offering psychological education to clients.

The brain can be divided into three main parts:

The Triune Brain Theory, proposed by Paul MacLean in the 1960s, remains relevant in understanding brain function during trauma. According to this model, the brain comprises three evolutionary structures—the neocortex, limbic system, and cerebellum—each with distinct functions that collectively govern how we think, feel, and react.

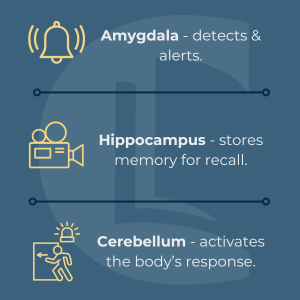

Several brain regions are particularly relevant to trauma-informed practice:

It’s important to note that the hippocampus, which stores video memories, fully develops around three or four years of age. This delayed development means that traumatic events occurring in early childhood might not be remembered as coherent narratives. Instead, such memories may manifest as fragmented snapshots or, in some cases, be completely inaccessible, leading to difficulties in processing and integrating these experiences later in life. This lack of memory can sometimes point to early trauma when clients struggle to recall events before a certain age.

However, an inability to recall childhood memories could be due to a condition known as Aphantasia. This condition can be experienced by those who are neurodivergent, and consists of being unable to imagine/visualise objects or situations, making the recollection of memories difficult.

When the brain perceives a threat, a well-coordinated sequence of events unfolds within a fraction of a second:

1. The amygdala detects the threat and sends signals to the thalamus and hypothalamus.

2. The hippocampus begins encoding the event as a memory, which can be recalled in similar situations in the future.

3. The brain reallocates blood flow. This reduces activity in the frontal cortex and increases it in the limbic system to prepare for action.

4. The cerebellum then activates the body’s fight, flight or freeze responses.

Cortisol, a stress hormone produced by the adrenal glands, plays a crucial role in the body’s response to perceived threats. As it travels through the polyvagal system, cortisol triggers the brain’s survival instincts, particularly activating the limbic system. This hormone helps prepare the body for fight, flight or freeze responses by increasing blood flow to the necessary muscles and organs while shutting down non-essential functions, such as digestion and rational thinking in the neocortex.

Understanding these brain functions is essential for practitioners. Recognising how quickly a client can shift from calm to a freeze response can inform how you approach interventions, particularly in managing trauma reactions within a session. This knowledge allows therapists to create a safer environment and guide clients through their experiences with a more informed perspective.

Overview of Brain Function – Key Insights for Trauma-Informed Practice

By understanding the brain’s functions and its response to trauma, counsellors and psychotherapists can enhance their practice, offering more effective support to clients dealing with the aftermath of traumatic experiences. The insights gained from this overview should encourage practitioners to reflect on their approaches and consider the physiological underpinnings of their clients’ behaviours and reactions.

Northoff, G. (2012). Psychoanalysis and the Brain – Why Did Freud Abandon Neuroscience? Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3317371/

Segal, D. (2016). Dr Dan Siegel. Available at: http://www.drdansiegel.com/

van der Kolk, B. (2016). Trauma Center. Available at: http://www.traumacenter.org

Mikkelson, D. (2016). The Rescuing Hug. Available at: http://www.snopes.com/glurge/healinghug.asp

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us