Three-Stage Recovery Model: Essential Trauma Therapy Insights for Counsellors

The three-stage recovery model introduced by Judith Herman is a central framework in trauma therapy, providing a structured approach to understanding and guiding recovery. This model offers therapists a step-by-step method to navigate the complexity of trauma recovery, emphasising the client’s safety and autonomy. As trauma-informed practice becomes increasingly integral to therapeutic work, this model offers a critical lens for understanding the client’s journey from the establishment of safety to the reintegration into ordinary life.

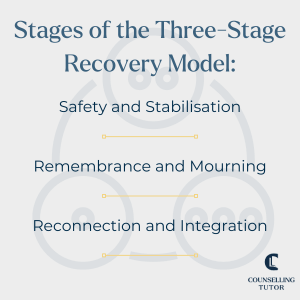

This article explores Herman’s model in depth, breaking down the three stages of recovery: safety and stabilisation, remembrance and mourning, and reconnection and integration. Through each stage, the therapist’s role is crucial in fostering an environment where the client can safely progress through their trauma without being rushed, ensuring recovery is sustainable and empowering.

Learning Outcomes

- Understand the three stages of the recovery model and how they apply to trauma therapy.

- Identify therapeutic techniques to support clients through each stage of recovery.

- Recognise the significance of safety and client autonomy in the trauma recovery process.

- Integrate insights on managing therapist-client boundaries, particularly regarding the importance of respectful reparenting.

Stages of the Three-Stage Recovery Model

1. Safety and Stabilisation

The first stage of Herman’s model is establishing safety, which is foundational to all subsequent therapeutic work. Clients must feel both physically and emotionally safe before they can engage with their trauma.

Another critical stabilisation aspect is your role as the therapist in building rapport and ensuring clients feel comfortable sharing personal details. Trauma-informed counsellors must be prepared to disclose small amounts of personal information if clients inquire about them, as this can aid in establishing trust. Judith Herman emphasises that knowing who is “holding the rope” during a challenging climb is essential for the client’s sense of safety.

Additionally, stabilisation involves reducing crisis and chaos in the client’s life. This might include helping them create a space of normality within the therapeutic environment, where they feel secure enough to begin exploring their trauma. Often, clients experiencing trauma feel unsafe both externally (in their environment) and internally (within themselves). Counsellors can help clients understand the difference between internal and external realities and assist them in learning techniques to manage hyperarousal and other trauma-related symptoms.

This stage involves:

- Stabilisation techniques, such as psycho-education, boundary-setting, and self-regulation strategies, are essential for managing hyper/hypoarousal symptoms.

- Counsellors and psychotherapists should not force disclosure or progress too quickly, a sentiment echoed by John Shlien’s metaphor of the poppy flower: forcing the petals open damages the flower. Similarly, clients must be allowed to process trauma at their own pace.

- The therapist’s role in this phase is to reduce crisis and chaos in the client’s life, create a safe space, and offer tools for distinguishing between internal and external realities, especially for clients prone to flashbacks.

2. Remembrance and Mourning

The second stage involves reconstruction of the trauma through remembrance, often accompanied by mourning. Clients may experience this as a timeless descent with no clear endpoint.

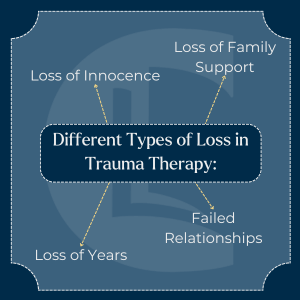

In this stage, clients might also express grief over various losses in their lives, including the loss of innocence, failed relationships, and even loss of family support. Herman points out that trauma survivors, especially those who experienced abuse within families, often face rejection or disbelief when they disclose their trauma. This isolation compounds their grief, as the trauma frequently severs family ties, sometimes irreparably.

Mourning may also take the form of loss of years—clients often reflect on how much of their life has been consumed by the trauma, feeling as though they’ve been robbed of time that could have been spent in healthier relationships, fulfilling careers, or personal growth. These observations highlight the multifaceted nature of grief in trauma recovery and the importance of the therapist being a witness to this process, providing empathy and support without rushing the client.

The practitioner’s role is to help clients process these losses, including:

- Loss of innocence, particularly for survivors of childhood abuse and failed relationships due to trauma, both within families and with external systems like workplaces.

- Providing space for clients to recount their trauma without the pressure of time or expectation. Clarity, trust, and courage are necessary for therapists and clients during this period.

3. Reconnection and Integration

In the third stage, clients work towards reconnection with their world and integration of their trauma into a new sense of self. By this point:

- They regain trust in relationships, knowing when to extend trust and when to withhold it.

- This phase involves reparenting—a term that describes the therapist’s role in modelling healthy boundaries and relationships. For survivors of abuse, this can include re-learning healthy sexual relationships, often a challenging aspect of recovery.

A significant part of reconnection is the survivor’s ability to form and sustain healthy relationships, including sexual relationships. For many survivors of sexual abuse, rediscovering their sexual identity and preferences is a crucial challenge. Judith Herman and many trauma practitioners note that survivors often grapple with their sense of self in intimate settings. Sexual preferences may have been imposed upon them, leaving them uncertain about their true desires.

As clients progress, they might reach personal milestones, such as being able to enjoy intimacy without associating it with their abuser or feeling the need to protect their abuser. These moments signify the client’s growing autonomy and ability to live without the heavy burden of past trauma dominating their current relationships.

Testimonies from survivors highlight the difficulty of this stage. Many survivors describe moments where they realise they no longer need to protect their abuser or feel safe enough to experience pleasure without trauma associations. For therapists, witnessing these breakthroughs is a sign of profound recovery.

Final Remarks

The Three-Stage Recovery Model is a thorough and humane approach to trauma therapy. It emphasises client safety and respects their autonomy throughout the recovery process. By allowing the client to control their pace, the therapist facilitates a recovery that respects the complexity of trauma. Given the demanding nature of this work, supervision and self-care for therapists are critical. Understanding what can be achieved within a limited number of sessions is essential for maintaining realistic therapeutic goals.

Therapists must stay attuned to the emotional toll of trauma work, balancing client needs with their capacity. Trauma-informed therapy is emotionally intense and often requires therapists to seek ongoing professional support. Regular discussions in supervision and peer consultations can help maintain your well-being and effectiveness. A supportive work environment ensures you and your clients are given the space and time necessary for meaningful, sustained healing.

References and Further Reading

Herman, J. L. (1994). Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence – From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. New York: Basic Books.

Shlien, J. (2003). To Lead an Honorable Life. Ross-on-Wye: PCCS.