Trauma Informed Practice Course

The Competence and Confidence to Work with Trauma in Your Practice.

The following article is taken from our Trauma-Informed Practice course.

The Competence and Confidence to Work with Trauma in Your Practice.

Trauma can significantly impact individuals, altering their ability to stay present and respond to daily life. Counsellors and psychotherapists who have training in trauma-informed counselling practice play a crucial role in helping clients navigate these challenges through effective trauma-informed grounding techniques.

These methods bring clients back to the present, allowing them to feel safe and enabling their rational brains to engage.

This article explores how various trauma grounding techniques work, their application, and the importance of tailoring these methods to each client’s unique needs.

Trauma Grounding Techniques

Ken Kelly: We’re talking about trauma grounding techniques, Rory, if you can just give us a quick overview of what do we mean by trauma grounding techniques?

Rory Lees-Oakes: These are actions you can take should your client disassociate in the room.

When someone’s disassociating, it means they’re going back to the time of the trauma. In other words, they’ve got themselves an emotional time machine, and they’re experiencing all the emotions.

So trauma grounding techniques are ways that a therapist can bring the client back to present time, into the here and the now, because that’s where the work is done.

If clients are still experiencing the past, it’s quite difficult to do any meaningful work with them. Most therapists would agree that by bringing people into the here and now, prioritising safety and security, you can work with the emerging issues from the trauma and keep them safe.

Ken Kelly: I think that is so beautifully said, Rory. A real nice overview of that.

And I think that we can start off by exploring when we might use trauma informed grounding techniques with clients. And as you say, Rory, if you maybe see that disassociation, you may introduce a grounding technique, but I’m also mindful that if we know we’re going into some pretty traumatic material with a client, grounding techniques can bookend that. We can start the session with a grounding technique, bringing that client into the here and now, maybe bringing them into a more relaxed state before we start exploring what they choose to bring.

And of course, that’s if we have a heads up that they may be bringing something that is trauma related, Rory.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yes. It’s not unusual for clients to not disclose what’s happened to them, to talk broadly around the issues of the past. But there may come a point in the therapeutic relationship where a client wants to disclose.

And in that case, it’s really important, I think that first of all, we contract for that. It’s worth reminding ourselves that therapy is very contractual process, and we can have contracts for certain things outside our initial contract.

So we make an initial contract things, you know, availability, payment, that type of thing, but we can in session contract. So, if someone is talking about disclosing, I think a conversation about how the therapist can support the client, what the therapist may do, even a little bit of psychological education to give the client a heads up that when disclosing, they may find themselves drifting into the past.

And you ask the question can how do we know? When we work with a client, we get a good sense of the here and now of this client, the equal and present time. And as a consequence of that, if a client’s behaviour changes, their affect changes, how they present themselves. That’s a good indication. I’ll give you an example.

So you have a client you’ve been working with, we’ll call her Jessica for want of a better name. And what happens is that she decided to talk about the events that’s happened to her. And all of a sudden you notice the body language change, her voice changes. You may hear a voice that is slightly more childish.

That’s an indication that someone is slipping back in time. Into the time where the trauma happened. Once that part of the brain engages,if you’re not working in a trauma informed way, the client may find themselves stuck in that place.

An intervention to bring the client back into the here and now, to acknowledge that what’s happened is in the past, that the threats no longer there. I think that’s really important for some people who’ve had very bad childhood experiences, to acknowledge and to affirm that the threats no longer there.

So those are a few of the indications that we can see if a client is sliding back and some of the negotiations and contracting we can use to help the client remain in the here and the now.

Ken Kelly: 100 percent and, that is if you have an indication that the client may be bringing some material that is particularly heavy, or that may cross it into traumatic experiences.

The other side of that is when it’s not clearly indicated, because trauma is not always some past event that was absolutely life changing in every single way. I’m thinking, when we think of trauma, it can be a conversation that you had with somebody can trigger trauma and sit as trauma within the body.

And I know that when we are looking for telltale signs to indicate that we should use some trauma grounding techniques, we would look out for fight or flight. We would look at shutdown. And in fight or flight, we’re looking maybe raised shoulders, maybe the person is fidgeting more than they normally would, showing some kind of tension, maybe wide eyes, there may be shallowness of breathing. And this can indicate a fight or flight. I need to get out of here now, I’m not comfortable at the moment.

And of course on the other side of that is almost the flip side of the coin. It’s the shutdown, which is a way of dealing with extreme emotional stress and trauma, and that would be the person appearing dead, almost out of character, emotionless in your session room.

They may have a collapsed posture, so their body is slumped down. They may look sad, almost like they’re experiencing deep sadness, or grief. Is there anything else that we should be looking out for to give us the indicator that now is a good time to maybe turn to a grounding technique?

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yes, there’s a term that’s been used for a long time, it’s usually attached to the military, called a thousand yard stare. It’s when someone is just staring into the middle distance. As if they’re looking at something a thousand yards away, even though they’re sat in the room, and that is a good indication that they are in that traumatic situation.

People may start to cry, I’ve known people try to leave the room. The flight is so strong that they literally try to flee the room, and I’d say that was unusual, but I know it’s happened to colleagues of mine.

So those are the kind of things we’re looking for, that we support the client, we’re there for the clients in every way and are able to not only bring them back into the here and now, but for ourselves to act as a regulator. For ourselves to be that regulating influence, to be that calm influence in the room, and I think that’s something that’s not really talked about a lot.

There’s two people in the room, one of those people has to be totally regulated. Has to be able to model regulation, but also for the client to look to the therapist and feel that there is safety.

Ken Kelly: Yes, it’s almost a grounding technique in itself of how we present as the counsellor within the therapy session.

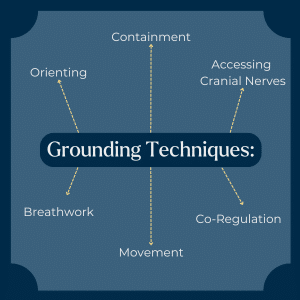

We can be a grounding anchor there. And now what I’d like to do is explore the different types of grounding techniques. So orienting, breathwork as an example of that.

Rory, I wonder if you can talk us through what is happening with orienting that client. I know that it’s bringing them into the here and now, we might use breath work to do that. Can you give an example of what we might use and what that does for the client?

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yes, part of helping to regulate is regulate the physical side of our bodies.

It’s not just the mind, it’s the entire ecosystem of our bodies. So using breath work, things like breathing techniques. Breathe in, count to four, breathe out, count to four. That can help the flow of cortisol and the adrenaline that cortisol triggers.

So when we’re in a fight or flight situation, our body produces cortisol and that sets our brain into a certain path. And then we’ll find adrenaline pumps, and people shake or feel like they need to run away.

So if we can arrest that by using something like a hand on the heart technique, place one hand on the heart and the other on the forehead and breathe deeply until a sense of calm is achieved and I think if the therapist models that, what will happen is that the physiological side of the body will start to regulate the brain. So that’s one technique.

The other, of course, is the butterfly hug, where you cross your arms over the chest and opposite shoulder and gently tap yourself, and that’s a way of regulating. And I think it’s very useful that the therapist teaches this, introduces it, teaches it. And I think crucially, Ken, that they may just teach it before the client goes in to any difficulty. So it’s no good teaching people how to use a life raft when the ship’s sinking, you need to teach people how to use a life raft as part of sailing in a ship.

If you’re working with trauma, it might be useful if you think the client may be struggling, or they say they may struggle, to introduce those techniques. And get them to practice them at home as something they could take away and use in their everyday life.

Ken Kelly: Yeah. We started with orienting, which is directing attention to the present moment and looking at the breath. We said when looking for signs, we might see a shallowness in breathing or a quick pace in breathing. By bringing attention to the breath, and using a breathing technique, and you outlined one there beautifully, Rory,

you’re engaging the brain, the thinking. I have to think about that. I have to be here in the present moment to control that breathing. Suddenly I’m controlling the breathing rather than it happening subconsciously. And that really can bring somebody into the here and now.

You mentioned some of the containment techniques as well. Now, containment is really helping a client feel safe within their own body. The thing about trauma is that the person doesn’t feel safe even within their own body. And that’s a horrible place to be because there is nowhere to go.

Containment brings the person to feel safe in their own body. And you mentioned the butterfly hug, it’s just crossing your hands over. And that kind of almost feels like I’m being held or contained. And then the tapping, you can tap two times on one side, two times on the other side. Again, we’re now involving the brain. We’re giving the brain a job to do that is not running away with the story that happened in the past. It’s in the here and now. I feel contained, I feel held, it’s almost like I’m being hugged, but it’s myself hugging. And I’m giving concentration on what I’m doing for the client to bring them into the here and now.

And clients may share that they sometimes experience panic attacks or high anxieties, this is a great technique that can be given to a client that can be used in any kind of situation. As you said, Rory, it’s a little difficult to teach that when somebody is within the traumatic event and they’re lost in that.

We’ve already mentioned psychological education, that’s also a grounding technique because you’re saying it’s okay to feel this way. Sometimes with trauma, as we’ve touched on, perhaps the trauma wasn’t some massive traumatic event like a car accident, it could have just been a conversation. Very often a client may feel silly for feeling those levels of anxiety just over a conversation they had, and just normalising that and making it okay, it can act as a grounding technique there.

And then of course, Rory, I think we should put in movement and how important movement can be as a grounding technique.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Absolutely, and I think the thing with grounding is the clue really is in the name. So if a client wants to tap their foot onto the floor, that’s grounding.

And as Ken has rightly observed, what these techniques are, is to try to keep the top of the brain, the cerebral cortex, engaged. Because in trauma, what happens is that the limbic system, the middle part of the brain, takes executive control.

So here’s an example, you are rushing around, trying to get out of the house. You can’t find your car keys and you run around and you get more and more stressed, you can’t find your car keys anywhere. And eventually you just give up, sit down, and start to calm down. Then all of a sudden you see the car keys on the table. What’s happened there is your brain has got into a stress mode, that middle brain is taking command.

The top of the brain hasn’t really been able to identify, or think the solution through where these keys are. And it’s only when you take a step back, sit down, that, that top brain then re-engages. And then you think, oh, I put them on the table all the time. And you feel silly and then you get in your car and drive off.

So with things like movement, what you’re doing is you’re engaging the whole body. People can tap or drum or move the feet or walk around. I’ve had clients walk around when they’re feeling an anxiety attack. But also crucially what it does, the movement engages the entire brain, because the entire brain is involved in the moving, the walking, the navigating, not walking into walls, not falling over. And that then controls that middle part of the brain where the stress lives, and it becomes a little bit more manageable.

So that’s why movement’s important.

Ken Kelly: It is, Rory. And if you think about a counselling session, it’s rare that a client would stand up and walk around within the room. We need to give permission, we need to set the stage for that. This is co-regulation, with us indicating that it’s okay to do. You might say something like, looks like you have a lot of pent up energy, I wonder if walking around might calm you down. You could do a breathing technique as the person is walking, you can say walk around the room, stretch your legs and let’s do a 1234 breathing exercise, something like that.

You can mix and match these and bring them together. At the end of the day, you’re looking to bring that client into the here and the now. Trauma is a complex topic.

There is a lot to cover in trauma. And one thing I know for sure is that trauma. Walks into every single therapy room at some stage, more often than we would hope.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yes, and I think with the world that we live in, it’s becoming more and more recognised, more and more seen.

And clients, I think, are more educated on it. I think clients may very well come to your therapy room, and talk about it. Wasn’t the case many years ago when I trained because it wasn’t discussed as much, it wasn’t highlighted as much. So, if you are working with clients, trauma informed practice, I think it’s pretty much an essential care.

Trauma is an internal reaction to distressing events, manifesting as an unhealed wound that impedes a person’s emotional and cognitive flexibility. Gabor Maté highlights that trauma isn’t about what happens to someone but about how they internalise and react to it. This unhealed trauma can keep individuals in a hyper-vigilant state, making it challenging for them to stay in the present.

Trauma is not what happens to a person, but what happens within them. In line with its Greek origins, trauma means a wound – an unhealed one, and one the person is compelled to defend against by means of constricting his or her own ability to feel, to be present, to respond flexibly to situations.

Gabor Maté (Hoffman Institute, n.d., para. 3)

The body’s response to trauma involves increased cortisol and adrenaline, mobilising defensive actions, e.g. fight or flight. Ideally, the body returns to calm once the threat is gone. However, unresolved trauma can leave these stress responses active, keeping individuals in a state of constant alertness or shutdown (Schwartz, 2020).

‘Traumatised people feel chronically unsafe in their bodies. The past is alive in the form of a gnawing interior discomfort. Their bodies are constantly bombarded by visceral warning signs.’

Bessel van der Kolk (2015, p. 97)

Before your clients begin to explore something traumatic, you might practise some of these with them so that they know that they can find a way back to the here-and-now safely. Agree which one or two work best for the client, how you might use them in the therapy room, and how the client might also use them outside the therapy room. Notice when they may be moving into defensive, survival responses (fight, flight, freeze or collapse), and remind them of the agreed techniques.

Remember: Rational thought is difficult to access in these states, so we need to calm the body before we can engage the brain in rational thought.

As therapists, we can identify when clients need grounding by observing their defensive survival responses. These responses typically manifest in two primary states: fight-or-flight and shutdown.

By recognising these signs, therapists trained in trauma-informed practice can use appropriate grounding techniques to help clients to regain a sense of safety and to reconnect with their rational thinking.

Trauma-Informed Grounding Techniques: Essential Tools for Therapy

Psychoeducation plays a crucial role in trauma therapy. By explaining the physiological basis of grounding techniques, therapists empower clients to understand their responses and actively participate in their healing journey. This fosters trust and collaboration between the therapist and client, leading to more effective trauma treatment.

Therapists must be vigilant about the risks of re-traumatisation and vicarious trauma when employing grounding techniques. The techniques themselves, if not appropriately applied, can trigger distress or exacerbate existing trauma. Establishing a safe and trusting therapeutic relationship before introducing grounding exercises is crucial.

Grounding techniques should always be an invitation, not a mandate. Clients should feel empowered to choose which techniques resonate with them, and have the autonomy to decline any that feel uncomfortable or unsafe.

Informed consent is paramount. Therapists should thoroughly explain the rationale behind each technique, ensuring that clients understand the potential benefits and risks. This empowers clients to make informed decisions about their therapeutic journey.

Care must be individualised: each client’s trauma history and nervous system responses are unique, and what works for one client may not work for another. Therapists should avoid making assumptions and remain adaptable, tailoring their approach to each client’s specific needs.

Orienting involves directing attention to the present moment through sensory awareness. This technique, often called ‘grounding’, helps clients to connect with their immediate surroundings and reduces feelings of dissociation (Schwartz, 2020).

Practical steps:

Containment techniques help clients to feel safe within their own bodies, creating a sense of boundary and security (Levine, 1997, 2010).

Practical steps:

Engaging the cranial nerves can help to activate the social engagement system, promoting a sense of safety (Levine, 1997, 2010).

Practical steps:

Controlled breathing exercises help to regulate the autonomic nervous system.

Practical step:

Physical movement can help to dissipate excess energy and bring clients back to the present. Encouraging clients to move – whether rocking, swaying or walking – can help to dissipate excess adrenaline and cortisol. Movement allows clients to process their mobilised state and to return to calm.

Practical step:

Creating a safe, calm presence in the therapy room can help clients to feel more secure. Through co-regulation, therapists can provide a calming presence for clients.

Practical step:

Trauma-informed grounding techniques are essential tools for counsellors and psychotherapists. By understanding the body’s response to trauma and applying tailored grounding methods, therapists can help clients to reconnect with the present and feel safer within themselves.

These techniques, grounded in theories such as the polyvagal theory, offer practical ways to support clients in their healing journey. It is crucial to practise these techniques with clients, explain their purpose, and adapt them to individual needs to ensure their effectiveness.

Trauma-informed grounding techniques can be powerful tools for healing, but they must be used with sensitivity, respect and a deep understanding of the client’s experiences. By prioritising safety, collaboration and informed consent, therapists can create a therapeutic environment where clients feel empowered to explore and heal from their trauma.

By integrating these grounding techniques into their practice, therapists can provide more holistic and effective trauma therapy, helping clients to navigate their trauma and move towards recovery.

Trauma-Informed Grounding Techniques: Essential Tools for Therapy

A: Trauma‑informed grounding techniques help anchor clients in the present to reduce dissociation, regulate the nervous system, and enable access to rational thought. They create safety before trauma processing begins and include methods like orienting, movement, and breathwork.

A: The 5‑4‑3‑2‑1 technique grounds individuals in the present by naming five things they see, four they feel, three they hear, two they smell, and one they taste. It uses sensory input to calm the nervous system and reduce dissociation during trauma responses.

A: Grounding techniques should be introduced early in therapy or when signs of dissociation or survival responses appear. Counsellors collaborate with clients to choose methods that feel safe, providing psycho‑education and ensuring consent throughout.

Dana, D. (2018). The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation. New York: Norton.

Dana, D. (2020). Polyvagal Exercises for Safety and Connection: 50 Client-Centered Practices. New York: Norton.

Hoffman Institute. (n.d.). Trauma, resilience and addiction: Hoffman interviews Dr Gabor Maté [online]. Hoffman Institute. [Viewed 3/7/24]. Available from: https://www.hoffmaninstitute.co.uk/trauma-resilience-and-addiction-hoffman-interviews-dr-gabor-mate/

Levine, P. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. Berkeley: North Atlantic.

Levine, P. (2010). In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. Berkeley: North Atlantic.

Maté, G. (2018). In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction. London: Vermilion.

Porges, S. (2017). The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe. New York: Norton.

Rosenberg, S. (2017). Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve: Self-Help Exercises for Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, and Autism. Berkeley: North Atlantic.

Schwartz, A. (2020). The Post Traumatic Growth Guidebook: Practical Mind-Body Tools to Heal Trauma, Foster Resilience and Awaken Your Potential. Eau Claire: PESI.

van der Kolk, B. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma. New York: Penguin.

Counselling Tutor provides trusted resources for counselling students and qualified practitioners. Our expert-led articles, study guides, and CPD resources are designed to support your growth, confidence, and professional development.

👉 Meet the team behind Counselling Tutor

💡 About Counselling Tutor

Counselling Tutor provides trusted resources for counselling students and qualified practitioners. Our expert-led articles, study guides, and CPD resources are designed to support your growth, confidence, and professional development.

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us