Your Free Handout

Moral Injury in Therapy

Moral injury is an emerging concept of profound importance to therapeutic practice, particularly in a world grappling with complex ethical, emotional, and existential challenges. Originating from work with military veterans, the term refers to psychological, emotional, and spiritual suffering following events that violate personal and deeply held moral beliefs. But it is not limited to the battlefield; it surfaces in healthcare, social services, journalism, and, significantly, within the therapy room itself.

As a psychotherapist or counsellor, your role often places you at the intersection of personal values, ethical considerations, and deep emotional distress. Understanding moral injury is therefore not just academically enriching but crucial for effective, compassionate care.

Moral Injury in Therapy

From this exploration, you will gain:

Ken Kelly: Moral injury, what is it?

Rory Lees-Oakes: The reason this topic is so pertinent is that it’s not often we see a presentation that we see in clients on a regular basis being recognised without pathology. In other words, not saying it’s a mental health condition or there’s something wrong, or we could give you pills to treat it.

For those who know DSM, Diagnostic Statistical Manual, which is basically a diagnostic book that psychiatrists use. Moral injury has been added in to DSM as a adjunct to post-traumatic stress.

And moral injury is where our moral compass has been shattered by a decision or a set of actions we’ve had to take.

It’s a very tricky presentation to identify because of the shame that’s attached to the actions that person took.

It may take a long time for moral injury to appear in the therapy room.

Ken Kelly: Rory, you’ve given us an explanation of what it is. I have a definition here, and you can get this definition in the handout.

But what is moral injury? Moral injury is the psychological, emotional and spiritual distress that occurs when a person feels that they have transgressed, or been betrayed, or forced into actions that violate their core moral values. It can come from two places. Moral injury can come from within self, from a decision that we made, from an action that we took at a certain time in our lives that there is shame, regret, and remorse about that is not resolved. But it can also be that we’re in a situation where you don’t have any wiggle room. Where, if you’re in a medical setting, you’re not making the decisions necessarily yourself, there’s gonna be rules and regulations that are imposed by others that we have to follow within those. And it can be imposed from externally.

Moral injury hides, it hides itself. That is its nature. It does not show itself because it is based in shame and regret and remorse. How could I do that? What was I thinking? So I wanna hide that aspect of me, I don’t want to show it to the world because the world will judge me as I am judging myself.

And I think when you mention Rory, that within therapy, I think it’s about patience. It’s about recognising that moral injury does exist, but it’s about that patience, recognition of that person, and that unconditional positive regard because moral injury hides from judgement of any kind.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yes, I like the way you said that. I like the aspect that it’s a hidden presentation. It’ll hide in a number of ways, Ken, and we all know that the bodyguard of shame is that secondary emotion of anger.

So if you are working with client and they’re angry think of anger as a secondary emotion, a bodyguard of emotions that are too powerful, too raw, too shameful to manifest themselves in the therapy room.

Then we have a clue of what might be going on for the clients. And through my practice experience, I’ve worked with a lot of angry clients and when you patiently wait and set the conditions for a client to speak about what’s really happened to them.What happens is the anger subsides and then, from behind the anger, comes the real issues. And that’s usually shame, or regret, or embarrassment, or fear of being judged.

It may not be healing, may just be resolution, it may be I have no choice. An example of that I’ve worked with military personnel who’ve taken life.And, I think it’s easy to say taken life. It was a case of if they didn’t take life, that life they took would’ve killed them.

That’s the realities of war that sometimes we turn our face from. And once that appears in the therapy room, and once that can be laid out and explored, what happens is there may be a coming to terms with it, it may be a settlement, not a cure or a resolution, but a settlement.

And that is, that unfortunately is just the nature of it, and I’ll just have to live with it.

Ken Kelly: Yeah it’s interesting, isn’t it?

So you’re speaking about if we look at PTS, that is usually based in a fear response and it’s like moral injury shows itself as a values mismatch.

So there can be fear associated with it and it can bring it up. But that values mismatch and PTS, when we’re speaking about moral inventory, it doesn’t dissipate with time. So we may have things that we do in our life where there’s an element of regret around it.

We go, I wish I hadn’t done that, what can you do? And we might be able to move on, and that feeling might dissipate. And with moral injury, it doesn’t dissipate. It stays within the person. It’s almost as a toxicity loop that just plays out and plays out. And it can be something that happened in the person’s childhood that they’re still playing over and revisiting in their adult life with the emotions being as strong, if not stronger than they were at the time that the event played out.

The way they said the wrong thing or did the wrong thing, or the thing that they feel that moral injury around, and it doesn’t show itself, it doesn’t dissipate.

So it is tricky and it is important that we look for it within therapy.

And it’s unlikely that person is gonna sit down in a therapy room and after session number two, start bringing this all out. It takes time, it takes trust within the relationship.

But we as the therapist, need to look out for some of the signs that we might see.

And I wanna ask you, Rory, what might we see in a client that might be a veil over this moral injury, that might give us an indication to dig a little bit deeper there.

Rory Lees-Oakes: It’s the way people talk about things, so as I’ve said, anger, is a good sign. If someone’s angry about a situation, pay attention to what that anger is protecting.

Almost certainly anger is a secondary emotion. So what is behind that? What are the primary emotions? And also if somebody comes to you and they may be talking about something, oh, this happened but I don’t do it anymore. I was in the army and making light of it, making light of things. Sometimes that’s an indication that the way they’ve dealt with it is to laugh it off a bit.They may just be very dismissive of something, but it keeps coming up.

They talk about it, and it keeps recurring. That can be a sign of moral injury.I would say we’ve talked about, very obvious areas of moral injury such as war, such as triaging in a medical facility. But it can be something such as someone struggling with the death of a parent.

Any presentation where there’s been, difficulty in childhood, disruptive childhoods. Usually, if you listen very carefully and wait long enough you will see moral injury start to manifest itself in the conversation.

Ken Kelly: Yeah and it’s alluded to in the handout as well, so signs and features of moral injury, intense shame, guilt, self condemnation, and that’s an interesting one, feeling betrayed by others, institutions or leaders. Not being able to get over that and feeling that intense betrayal by someone else. Loss of trust in self, or the world. You can’t look to other people because I’ve been let down in the past, withdrawing from others due to feelings of unworthiness. It can be an indicator and it’s important that we as counsellors recognise this, that we see it, that we know about it, and we do a little bit of CPD on understanding what moral injury is because there is a risk of misdiagnosis.

It may show itself as depression, anxiety, and the moral dimensions of that can be missed when we’re looking at symptoms and we’re not looking at the inside because it’s based in values and values being overthrown. So that’s interesting.

Trust issues, clients may be reluctant to disclose, fearing of judgement.

Specifically if we’re talking about somebody who may feel betrayed by other institutions, they may arrive with us in counselling and psychotherapy and be reluctant to say how it is for them, because they’ve been let down in the past and they carry that with them. And counsellors can offer a safe, non-judgemental space where moral conflicts can be heard and validated.

I think that is a step into the path of healing, Rory.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, it is.

Supporting, clients in retelling their story, being compassionate to themselves as opposed to being judgemental. And I think that is a way for therapists to help clients generate that self-love for themselves.

And also I think externalising language, talking about it as an experience, not as an identity.

I think that is taking away the personal aspect of it and saying, what would others have done in that situation? And once you do that, once you move away from that very personal side of things, people might say, probably have done the same thing, may not make it any different, but might give the sense that they just didn’t act only on their own, that other people in the same position would’ve done the same.

And I also think that there’s a renegotiation, isn’t there here. With any moral injury, what you’ve done is you’ve broken your compass, also you’ve broken your values, the values that you’ve lived by, and I think sometimes it’s about reintegrating the values.

Trying to look and help the clients explore that this was one incident, one thing that happened, but in the whole canopy of their life, their values are intact. That they do things in their life where they can make decisions, where they act in a way that fits their values.

So it’s about the entire identity of the client.

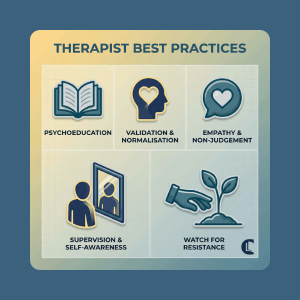

Ken Kelly: Yeah, it is. And in the handout that we have, there is actually seven areas of intervention and approaches that you’ve covered, Rory. The one that you’ve just touched on here that I really value, is that normalising and that psychological education, that it’s okay and it is normal and normalising the shame, really, without colluding in that self condemnation part of things. Because it is something that we experience as humans.

But as you say, Rory, it takes a deep understanding and it takes some deep work.

So we have a handout for you, it is the moral injury handout. It explains DSM and how moral injury is now part of DSM. It’s got some great references for including a glossary that Rory has put on, and it’s gonna walk you through what DSM is, what moral injury is, the recognition within DSM, signs of moral injury, why counsellors need to be aware of that, and then there are seven interventions that kind of speak for themselves, and a key takeaway there as well.

So if you want to grab that, it is free of charge. Any last sentence to take away from this Rory?

Rory Lees-Oakes: Work with your supervisor, a good supervisor. If you’re working with someone who’s presenting with anger or there may be being a bit elusive in the therapy room. Speak with your supervisor and be patient.

They’ve come to you because at some level they want to talk about what’s happened and your job as a therapist is to be patient, is to wait and wait, and eventually the real issue will come out.

It will appear, but you have to be very patient.

Moral injury, as defined by Jonathan Shay (1994), is the psychological distress that results from actions, or the lack of them, which violate one’s moral or ethical code. The injury often stems from a high-stakes situation where there is a perceived betrayal, either by oneself or others.

Moral injury isn’t restricted to professional life. Consider Robert, a father who, while exhausted from working two jobs to care for his ill wife, accidentally caused a fatal car accident involving his son. The tragedy unfolded from a cascade of minor decisions made under immense pressure, decisions that Robert later perceived as moral failings.

This case illustrates that moral injury can arise in domestic and deeply personal contexts, and clients may present with shame and self-condemnation long after the event has occurred.

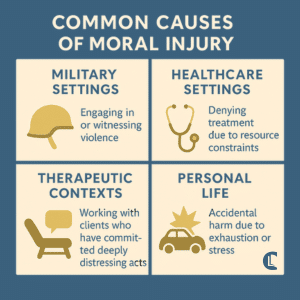

Moral injury can stem from:

Importantly, even witnessing an event without active involvement can cause significant distress. Therapists should not overlook this form, especially in clients such as healthcare workers, journalists, or emergency responders who are often present at traumatic scenes without the power to intervene.

Moral injury is not classified as a mental illness, but its effects are profound and often overlap with symptoms of PTSD, depression, and suicidality.

Unlike PTSD, moral injury does not necessarily involve threats to physical safety. Rather, it threatens a person’s core sense of right and wrong, undermining moral identity.

Moral injury often emerges over time. An event that felt justified or necessary in the moment may later be reevaluated under a different lens, especially when the individual re-enters a more peaceful or morally consistent environment.

For example, soldiers may not fully process the emotional impact of actions taken in combat until they return home. Similarly, healthcare professionals might only later realise the moral weight of decisions made during high-pressure situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therapists must tread carefully when addressing moral injury. Exposure-based and traditional trauma-focused CBT approaches may be counterproductive, especially when the client’s beliefs and guilt are not irrational but rather accurate reflections of their experiences.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Promotes psychological flexibility and self-compassion through:

ACT has shown promising outcomes, particularly within military contexts, but its principles are broadly applicable.

When working with moral injury, you may encounter clients who disclose acts that deeply challenge your own ethical framework, such as sexual abuse, violence, or neglect. While you are not required to condone such behaviours, it is crucial to:

Moral injuries may not manifest immediately. The impact can surface much later, especially when a client returns to an environment that reactivates moral reflection (e.g. a soldier returning home or a healthcare worker reflecting on post-crisis experiences). Therapists must remain attuned to this temporal dimension.

Moral Injury in Therapy

Moral injury is the deep psychological, emotional and spiritual distress that occurs when someone feels they’ve violated their own moral or ethical values, either by actions they took, didn’t take, or witnessed – and it doesn’t depend on direct physical threat like PTSD does. It often involves intense shame, guilt and loss of trust in self or others, and can overlap with PTSD symptoms but is rooted in values being transgressed rather than fear responses.

Moral injury can arise in many settings where someone’s core values are challenged, such as in military combat, healthcare decisions under pressure, personal life tragedies, or situations where a person feels they failed morally – including acts of commission, omission or witnessing harm without power to intervene.

Therapists support those with moral injury by offering a non‑judgemental space to explore shame and regret, using approaches like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), psychoeducation, and empathy to help clients reconnect with their values and build self‑compassion, rather than using traditional trauma treatments that focus only on fear-based symptoms.

Moral injury challenges us not only to support our clients through deeply painful reflections but also to examine our ethical foundations as practitioners. Its complexity demands nuanced, compassionate engagement and an openness to modalities that prioritise acceptance over correction.

As moral injury becomes more recognised beyond military settings, therapists are uniquely positioned to offer healing grounded in empathy, self-forgiveness, and renewed purpose.

Launder, A. (2021). Working with Moral Injury [lecture]. Counselling Tutor. CPD Library.

Evans, W. R., Walser, R., Drescher, K. D., & Farnsworth, J. K. (2020). The Moral Injury Workbook: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills for Moving Beyond Shame, Anger, and Trauma. New Harbinger.

Williamson, V., Stevelink, S. A. M., & Greenberg, N. (2018). Occupational moral injury and mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 212, 339–346.

Greenberg, N., & Tracy, D. (2020). What healthcare leaders need to do to protect the psychological well-being of frontline staff in the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Leader, 0, 1–2.

Feinstein, A., Pavisian, B., & Storm, H. (2018). Journalists covering the refugee and migration crisis are affected by moral injury, not PTSD. JRSM Open, 9(3).

Counselling Tutor provides trusted resources for counselling students and qualified practitioners. Our expert-led articles, study guides, and CPD resources are designed to support your growth, confidence, and professional development.

👉 Meet the team behind Counselling Tutor

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us