Free Handout Download

Counselling Clients Experiencing Ambiguous Loss

Ambiguous loss, as introduced by Dr. Pauline Boss in the 1970s, is a profound yet often overlooked form of grief. Unlike conventional loss, it leaves individuals in a state of limbo – grieving someone who may be physically present but psychologically absent or vice versa. This type of loss poses unique challenges to both clients and the therapists supporting them.

Counselling Clients Experiencing Ambiguous Loss

Ken Kelly: Rory, what is ambiguous loss?

Rory Lees-Oakes: Ambiguous loss is when someone or something is physically absent, but psychologically present. So let me give you an example of that.

Many of us. Have experienced our children going off for further education. My daughter went off to university and both myself and my wife felt a loss. We knew she was okay, but she wasn’t around, and it was a really strange sensation.

On one level, ambiguous loss can be experienced by a lot of people. Just thinking about your first romance and I wonder where they are now.

It creates a kind of disconnected feeling, a bit of a yearning in some cases. But when we talk about grief and what we see in the therapy room, I mean we can see both of the two examples I gave but What about someone who comes and says their partner was lost at sea or was in a natural disaster and they haven’t recovered the body?

It’s a very stressful form of loss because you don’t get the chance to say goodbye to the person.

It’s unfinished business. And I think it can apply to lots of areas in our life where people have had accidents and it’s changed their personality. People who have memory related problems such as Alzheimer’s or people in addiction, loved ones in addiction where the person they were has gone, they’re replaced by the addiction, sadly. That is ambiguous loss, and it can be one of the more tricky ones to navigate.

Ken Kelly: Thank you, Rory. Yes, it is tricky.

And the example that I was thinking of was losing your keys. So here’s two scenarios. One is going to be loss, and the other one is going to be ambiguous loss off one’s car keys. So if I am in the sea, and then I realise my car keys fall out of my jacket pocket and get carried away by the sea.

They’re gone. They’re lost forever. I know they’re gone and now I need to come to terms with that. They’re gone, I’m never going to see them again. It’s very different to going out on a walk or a hike and you get back to your car, and you look for your car keys and you can’t find them.

It leads to thinking of did I drop them while I was walking on the path? Do I go and walk the path again? What happens if somebody finds my keys? Could they take my car? And it leads to a whole lot of different thought processes because of the ambiguity. I don’t know what has happened.

And you spoke beautifully, Rory, of giving some examples of what that may look like.

And of course, I guess we could look at Alzheimer’s as being a form of ambiguous loss where you have the person right in front of you, they’re physically here, but yet they’re not. They’re not the person they once were. And you used a beautiful example speaking about addiction.

I can still see that person. They look the same, they sound the same, but it’s not them anymore. They’ve lost that part of that person, and it leads to a whole lot of different processes that are different to if the person was just lost and they passed away and they were gone, there’s a process of coming to terms with that, and we know what happened.

And I guess when we see ambiguous loss within the therapy room, the client might be bringing those processes around the ambiguity, not having closure, not having a clear understanding of what has gone on.

Have I understood that correctly?

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, you have. I mean, What one of the most predominant presentations is ends of relationships where someone has just walked out and not given the person a reason for leaving.

And of course it can lead to self blame, and double guessing yourself. I think another example, and the one that’s been in the press recently is that if someone has a brain injury, it could alter their personality. That person you married is no longer the person they were because they’ve had a brain injury.

The person is yearning to rekindle the person that they married. And of course, they’re gone because of the brain injury. So I think ambiguous loss is more common than we probably realise.

Ken Kelly: So I guess, we’ve got an understanding now of what ambiguous loss is, and I like Rory, how you’ve pointed to understand ambiguous loss in our clients, we can look in our own lives. And undoubtedly, if you look carefully enough with an understanding of what ambiguous loss is, you’re going to look at your own ambiguous loss and what feelings that come up around ambiguous loss for you. What does it feel like? Is it resolved? The next question is, does ambiguous loss link in with our understanding of other types of grief, Rory?

Rory Lees-Oakes: It links in with something called anticipatory loss, where a person is aware there may be death or loss of a loved one is likely and the grieving begins long before. That can be where someone has a life ending illness, terminal illness. It leaves their loved ones anticipating the loss of that person.

It can also lead to something called frozen grief, where the brain stops processing to help the coping mechanism of grief. They stop connecting with themselves or others, and are unable to proceed in their lives because they’re trying to resist the fact that someone’s gone.

They think that the whole thing was a bit of a facade, and at some point the person’s gonna walk through and go, hi, I’m back. And they just won’t believe anything else. So those two links are very strong, Ken, very strong. Anticipatory loss and frozen grief.

Ken Kelly: Yeah, and I guess we can add to that the disenfranchised grief, where the grief that the person feels, the loss that they feel can’t be shown. They have to hide it. There’s an incongruence there. I have to keep it buried, I’ve got to show a brave face to the world. But within, inside, I’m feeling very different to that, and I’m not able to show what that looks like. And I guess this brings us on now that we understand what ambiguous loss is, how it links in with other types of grief that we might study as counsellors and psychotherapists.

We then come on to our clients that come in and how we might work with ambiguous loss when it presents itself within the therapy room. And I think a good starting point is what does not work.

And in these kind of situation is sympathy. Hearing time is gonna heal, waiting for closure. Because of the ambiguity, closure does not just naturally come as it does through a natural grieving process. Absolute black and white thinking does not help around ambiguous loss.

Isolation, the person isolating themselves, just sitting on their own, does not shift it. It doesn’t go, it can sit with them. Blame, revenge, belief that bad things happen to bad people, and need always to be in control, and resisting change, are enemies of working with ambiguous loss. So I wonder, what does help?

What can we do as a counsellor, psychotherapist? We have a client they’re presenting, we can clearly see this feels to us like ambiguous loss. We can at some level definitely relate to what that person empathically might be feeling because we’ve looked at ourselves and explored what ambiguous loss is to us.

How might we work with that Rory?

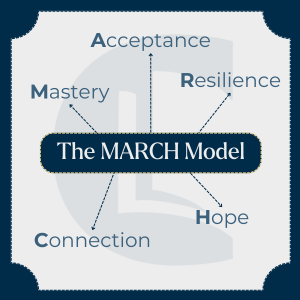

Rory Lees-Oakes: It’s quite interesting, because there is an organisation called Ambiguous Loss UK, and Chloe Swinton, who is a spokesperson for them, talked about something called the MARCH model, and it’s named after the first letter of it’s components: mastery, acceptance, resilience, connection and hope.

And the model’s summed up really, with the quote “you can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf”, and it’s really true. Helping someone to accept that person is gone is really important. Therapists are rather different to the vast majority of the population when they talk about death, because lots of people say they’ve gone to sleep, or they’ve moved on, or there’s lots of euphemisms for death. But actually, therapists do speak about death. I would say, your partner has died, because that’s the reality of it.

And I think that could be sometimes very helpful. It might sound incredibly insensitive and incredibly cruel. But to get to the facts of the matter, the reality where we’re at, or where the client is, I think it could be very useful. We have to be very thoughtful when we do that. Mastery is about helping someone take control of life, and realising that things are outside somebody’s control. You can’t control everything.

And acceptance, as I said, some level acceptance, not as a finality, but just to realise that the person has gone or in your case, the relationship has ended, and allowing grief. I think the thing with ambiguous loss is grief actually doesn’t kick in, because it’s held in suspension.

Allowing the grieving process, sitting with the client when they finally realise there is a loss here. And if it’s someone who is, we talked about people with dementia or Alzheimer’s, sometimes just understanding the process of that.

My grandson is autistic and he’s going to need a lot of support through his life. We love him to death. He’s going to need a lot of support even into his adult life. And, one of the things that we had to grieve as a family is that he wasn’t the person we thought he may be.

Everybody thinks of their children growing up and moving out, by researching and getting really involved in my grandson’s autism, it has been mighty helpful to come to terms with the loss of what we believed he would be. We love him to death and we wouldn’t have him any other way.

I think I speak for myself, I’m not going to speak for the rest of my family, but I think there is a loss process that had to be engaged with. And resilience, helping people be resilient, thinking about what learning is taking place during the loss. What have we learned?

What conclusions have we come to? And, I also think about promoting well being, emotional well being. And it could be physically, it could be spiritual, it could be religious, but making sure that helping the client maybe to look after themselves.

And that’s a simple thing, such as getting out a bit more, I’m going for a walk around the block, I’m going to meet friends. Just acknowledging that and saying, it sounds to me like you’re putting your well being first, and you’re looking after yourself and, discussing how that’s helping. So that’s quite a useful model to look at, Ken.

Ken Kelly: Very much. So, you’ve been through the mastery, you’ve looked at acceptance, you’ve spoken a little bit about the resilience side of things. And then, there’s connection. Being in a support group where others share the same kind of journey.

Just going back, there’s two sides to this.

The connection side of things, and then the other side of this is hope. But it’s not the false hope that the person is suddenly going to walk through the door, it is hope that you yourself going through this ambiguous loss can overcome this and find meaning within your life. Even if there isn’t closure, that hope that there is a way that you can find joy again in your present moment, because within hope, you can discover the purpose that is the fit for you.

So there’s some really interesting things on this ambiguous loss.

Any final thoughts?

Rory Lees-Oakes: I think being realistic. It may be that there isn’t a resolution to ambiguous loss, that people just have to live with it.

I think grief in general is something that doesn’t get any less, it’s just our lives expand around it. So it was thought for a long time with loss that it would fade, it would fade away as we moved away from the events or events that produce the loss. But the thinking now is that the loss is still as big years on as it was at the time, but what’s happened is our life has grown around it. And I think that’s a message of hope, because for those who have experienced loss, and I think every person probably listening to this has experienced it, just reflect how much your life has grown since the loss.

And what happens is your life just expands around it. And I think that gives hope, it’s certainly given hope for the losses in my life. Because as your life expands, it becomes hopefully richer, hopefully more connected. And, you never forget the people you’ve lost, but they’re not principally in your mind all the time, or hopefully not.

Ken Kelly: Yeah, beautifully said Rory a great topic.

Ambiguous loss refers to a loss that is unclear and unresolved, creating a profound sense of uncertainty and confusion. It is divided into two types:

The scale of ambiguous loss is significant. For example, in the UK alone, 170,000 people are reported missing each year, impacting an estimated 12 individuals for every case. Additionally, 850,000 people currently live with dementia, a figure projected to rise to 1 million by 2025. These numbers highlight this loss’s widespread and deeply personal nature, greatly affecting individuals and families.

Ambiguous loss can take many forms beyond the commonly cited examples of missing persons or dementia. Other examples include foster care or adoption, absent parents, or the grief experienced from ecological or biodiversity loss due to climate change. These varied scenarios underscore how clients might encounter this type of unresolved grief.

Clients experiencing ambiguous loss often feel caught between hope and hopelessness, as well as certainty and uncertainty. Unlike traditional grief, there is no closure – no funeral, no formal recognition. This can lead to “frozen grief,” where emotions remain unresolved.

The COVID-19 pandemic amplified experiences of ambiguous loss. Due to restrictions, many individuals were unable to say goodbye to dying loved ones, attend funerals, or find closure. For some, this extended to losses of plans, jobs, or a sense of freedom and stability. The prolonged uncertainty during the pandemic heightened feelings of grief, isolation, and anxiety about the future.

Developed by Chloë Swinton, the MARCH model provides a structured approach to navigating ambiguous loss:

Encourage clients to focus on what they can control and let go of what they cannot. Explore family roles and dynamics. When an ambiguous loss occurs, family dynamics often shift. Roles may change drastically – for instance, a spouse may become a full-time carer, or a parent may adjust to the absence of a child. Revisiting family traditions and boundaries in light of these changes can help clients regain balance.

Guide clients in finding ways to adapt and grieve, even without closure. Research and rituals can provide clarity.

Build coping strategies, promote “both/and thinking,” and maintain holistic well-being.

Encourage connections with self, others, and “psychological family” – individuals who bring comfort, alive or deceased.

Encourage connections with self, others, and “psychological family”—individuals who bring comfort, alive or deceased.

To illustrate the differences between death-related grief and ambiguous loss, consider the example of two clients: Sophie and Jane. Sophie’s husband passed away following a stroke. Her community supported her with rituals such as a funeral, condolence messages, and memorials. Jane’s husband, however, survived his stroke but suffered severe cognitive impairments. This left Jane in a prolonged state of ambiguous grief, caring for someone who was physically present but no longer the person he once was. Unlike Sophie, Jane received no formal rituals or ongoing community support, which compounded her feelings of isolation.

Therapists must examine their experiences of ambiguous loss to ensure they approach clients without bias. Personal therapy or supervision can be invaluable in this process.

Self-reflection can be further supported by exercises like naming your ambiguous losses or exploring moments where you’ve felt “in limbo.” Breathing techniques, such as the 4-7-11 method, can also help therapists stay grounded as they navigate these emotionally intense topics with clients.

Counselling Clients Experiencing Ambiguous Loss

Ambiguous loss redefines conventional understandings of grief, confronting both clients and counsellors with unique emotional and psychological challenges. This form of loss requires a nuanced approach that goes beyond traditional therapeutic models, embracing flexibility, patience, and innovation. For clients, ambiguous loss often feels like a relentless storm, leaving them uncertain. By creating an empathetic, supportive space, practitioners can provide the stability needed to navigate this emotional turbulence.

Adopting tools like the MARCH model equips practitioners with practical strategies to address the profound complexities of ambiguous loss. From helping clients find acceptance and resilience to encouraging connections and instilling hope, these techniques guide clients toward healing, even without closure. Beyond the therapeutic space, counsellors in practice must also remain mindful of their own experiences of ambiguous loss, engaging in ongoing self-reflection and supervision to ensure they can fully support others.

Ultimately, an ambiguous loss is a journey of adaptation and discovery – of finding meaning amid uncertainty and reclaiming purpose in the face of loss. As counsellors, you empower clients to weather the waves of grief, helping them rebuild and grow through life’s most uncertain challenges. By combining professional expertise with genuine compassion, you can make a huge difference in the lives of those navigating this intricate and enduring form of loss.

Boss, P. (2000). Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief. Harvard University Press.

Missing People/National Crime Agency Report (2019-2020). Key Statistics on Missing Persons.

Swinton, C. (2021). Counselling Clients Experiencing Ambiguous Loss. Counselling Study Resource.

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us