Trauma Informed Practice Course

The Competence and Confidence to Work with Trauma in Your Practice.

The following article is taken from our Trauma-Informed Practice course.

The Competence and Confidence to Work with Trauma in Your Practice.

In the field of counselling and psychotherapy, defining trauma is crucial for understanding and treating those affected. Trauma encompasses a broad spectrum of experiences and reactions, making it a complex concept to grasp fully. This article explores various definitions and perspectives on trauma to provide a comprehensive understanding that can inform your practice.

Understanding Trauma: Diverse Perspectives and Definitions of Trauma

Ken Kelly: [00:00:00] It is important to understand that trauma will show itself differently in different people because of different reasons. There is a diversity within trauma.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yes, within our practice, we have to recognise diversity, that people are different. And that can be many kinds of difference. When someone has suffered trauma because of who they are, that can lead to some complexities that we need to give real attention to.

There’s gonna be a lot of therapists listening to this who may be working with populations who are asylum seekers, who will hear stories of trauma just because of who someone is, or the colour of the skin, or maybe their religion, or their affiliations.

And that then expands to people who’ve experienced trauma because of their sexuality or their gender selection. We have to be thoughtful of that. We have to realise that, that’s a perspective that we need to keep in our minds, because it’s almost certainly going to be a perspective that the client’s gonna bring up. And that would look like the client saying, why would someone do this to me? Just because of how I look, or the colour of my skin, or my sexuality?

A few years ago there was a very prominent case of two lesbian women who were on the top deck of a bus, and they were attacked and suffered physical violence because of who they were. They were picked on because they were gay. There’s the trauma, and then there’s also the fact that the trauma was delivered because of who you are.

Sometimes it’s called dual burden. It’s the burden of having trauma just because of who you are. And that can lead to something called minority stress, where minority groups may experience stress at a different level than people who are not in a minority group.

So diverse perspectives and definitions of trauma, something that every trauma informed practitioner needs to have in the forefront of their mind when working with any client, because you never know what’s going to emerge within the arc of therapy.

Ken Kelly: You mentioned dual burden then, and I think that’s worth focusing on for a moment.

When we look at the definition of trauma, the American Psychological Association, defines trauma as an emotional response to a terrible event. So when that event is external to self, and that might be a car accident, or something like that, that is a certain kind of trauma.

But as you’ve said, Rory, when it is about who you are, and your very core of your being, the trauma is woven into that from external abuse. It does create that dual burden, and it needs to be looked at differently, and recognised differently.

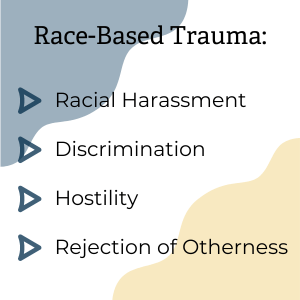

There will usually be harassment, discrimination, hostility, and a rejection of the otherness, or individuality, of that person. And that is difficult, because so often we look at ourselves and say, is this my fault? What is my part in this? That trauma can run very deep, and be very troubling and present within your therapy room.

Trauma can come about as a result of relationships, and that may be family relationships, or romantic, or partner relationships. It may be a marriage, and what happens within that relationship, and that’s another lens through which we might see the trauma.

And it’s a different lens through which the client will see themselves and their part in that trauma.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, absolutely. Ken. And you mentioned within the family, I think that is something that sometimes can be missed. If you’ve got someone who is a survivor of spousal abuse, I’m trying not to use the word victim, I think survivor is a more useful phrase in terms of therapy, then they may have experienced trauma because of who they are.

It’s probably natural to think of women who’ve experienced trauma. In my practice, I’ve many women who’ve experienced trauma because their partners have abused them because they’re women. But also, we have to acknowledge that there are men who suffer the same thing. So I think it comes down to what you said, Ken.

Otherness, where somebody is abused because they’re different. And that difference can be many things, it can even be someone who’s got special educational needs. And what happens is they’re picked on because they’re different. So an autistic child may be picked on because they’re different. So it’s not sexuality, gender, race, it’s otherness. It’s being and experiencing trauma because you are different to the group of people who are perpetrating that trauma.

Ken Kelly: Yeah, beautifully said Rory. Bessel van der Kolk, he’s written some defining work on trauma, and he describes being traumatised as a state where individuals organise their lives as if the trauma was still occurring.

And, you speak about otherness. I see otherness in myself. I’m very open that I am neurodivergent, I’m autistic. I’m diagnosed autistic in my fifties. And when I look back on my life, I realise the trauma and the responses to that trauma that I enact today from being a child. Feeling that I was outside the group, feeling that all the other children had it together, and I just didn’t really understand how it was.

Having very few friends, being bullied, having names being called to myself. And what is really interesting, Rory, is I went on to live my life, and developed ways of dealing with life as a result of that trauma.

Throughout the whole of my study to become a counsellor, at no stage did I recognise that trauma. It was so hidden from myself. If we were talking about the self-development exercise where we try and bring everything into clarity, it was unseen to self, and maybe unseen to others, and it just became part of how I would show up and act or interact within a setting. And studying trauma has made me look at my life differently and question how I show up.

Now, if I’m in a group of people, if I go to a networking event, I’m still feeling like that little, nine, 10-year-old boy. Being a little bit shy to walk up to people because they might reject me. And it’s acting from that traumatised young person. And I think that is what is so interesting for me is how we can study and we can learn about the theory and we can do the self-development, but trauma is tricky.

It can hide itself in the shadows.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah,and I think that we are now realising that it is not trauma with the big T. When I say trauma with the big T, you know when you talk, certainly to lay people who are probably not in our field, they would say things like war.

They would say things like serious industrial accidents, car crashes, witnessing horrific events, and no one would deny that they are traumatic. However, I think that now we’re beginning to acknowledge, and rightfully so, there can be small events in life that aren’t connected with wars or natural disasters, which set our brain, certainly the middle parts of our brain, which is where our fire alarm system isto be hypersensitive to situations.

And it’s really interesting because I live in a very small town, we both live in the middle of nowhere, I think it’s fair to say, Ken, but I went into my local town, which is Manchester the other day, and I noticed just how on high alert I was.

I’ve never been a soldier, I’ve never fought in a war, thankfully, but I did find myself being hypervigilant as I stepped off the train and saw literally hundreds of people at the train station, and I found myself using my phone, but stood a corner with my back to the wall using the phone. Which on the face of it, feels a little bit ludicrous, but then I thought to myself it is a place of safety, at least I can see what’s coming.

Throughout my trip in Manchester, I have to say that my amygdala was firing off. And when I got back on the train, I was speaking to my wife about it and, said this is partly because of my experiences as a younger man in Manchester, which was a very different place when I grew up, I have to say. The seventies was a very violent time, I think, but it never leaves you. You can rationalise it, and say, oh Rory, you’re being very silly here.

But actually, Bessel van der Kolk’s key phrase, if you like, the body keeps the score, if you amplify that for someone who may have a different skin colour, sexuality, gender preference, you can have people in innocuous situations, feeling threatened.

And as therapists, we have to be aware of that. Sometimes we have to give it a name. We may have to say to clients, feels like that wasn’t a very safe place, and acknowledge it.

Ken Kelly: 100%. As you were relating your story, your trip to Manchester, I was just looking again over that definition.

Being traumatised, a state where the individual organises their lives as if the trauma was still occurring. You find yourself there with your amygdala firing off in what is a regular situation, but that is how it is for you and how that plays out. It’s that recognition that trauma is not always the industrial accident, the big car crash.

It is more nuanced than that. Understanding trauma through these varied lenses broadens the scope of what trauma encompasses, but it also aids in the development of us as therapists for more effective therapeutic intervention.

So by exploring and acknowledging the different definitions of trauma, we can better support our clients.

According to the American Psychological Association, trauma is defined as an emotional response to a terrible event such as an accident, rape, or natural disaster. Initial reactions often include shock and denial, while longer-term responses can involve unpredictable emotions, flashbacks, strained relationships, and physical symptoms like headaches or nausea. This clinical perspective provides a structured understanding of trauma’s impact on an individual’s emotional and physical well-being.

Race-based traumatic stress injury is another crucial aspect, highlighted by Carter (2005), which results from emotional pain following encounters with racism. This type of trauma can manifest through acts of racial harassment, discrimination, or hostility, and it underscores the rejection of otherness that clients may face.

Recognising race-based trauma is essential in appreciating the unique challenges faced by those subjected to systemic racism.

The dynamics of trauma within interpersonal relationships are particularly significant. A widely accepted definition describes trauma as an event or series of events that are experienced as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening, leading to long-lasting adverse effects on an individual’s functioning and well-being. This perspective is especially pertinent in cases of domestic abuse, which can involve planned yet unpredictable harm within the context of a relationship. The complex nature of such trauma requires sensitive handling by practitioners to support recovery and resilience.

Bessel van der Kolk, a leading figure in trauma research, offers insight into the enduring nature of trauma. He describes being traumatised as a state where individuals organise their lives as if the trauma were still occurring, with every new experience coloured by past traumas.

This ongoing influence can reshape the nervous system, perpetuating a cycle of distress and hindered healing.

Van der Kolk’s work emphasises the need for a compassionate and nuanced approach to treatment, recognising the deep and lasting impact of trauma on the mind and body.

Understanding Trauma – Diverse Perspectives and Definitions of Trauma

Understanding trauma through these varied lenses not only broadens the scope of what trauma encompasses but also aids in the development of more effective therapeutic interventions. By exploring and acknowledging the different definitions of trauma, practitioners can better support their clients in navigating their experiences and healing journeys.

American Psychological Association. (2022). Trauma and shock. [online] Available at: https://www.apa.org/topics/trauma/

Carter, R. (2005). Handbook of Racial-Cultural Psychology and Counseling. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley.

Van Der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. Penguin Books Ltd.

Rees, S., et al. (2011). Lifetime Prevalence of Gender-Based Violence in Women and the Relationship With Mental Disorders and Psychosocial Function. Journal of American Medical Association, 306(5), 513–521.

Sharpen, J. (2022). Trauma-informed work: the key to supporting women. [online]. SafeLives. Available from: https://safelives.org.uk/practice_blog/trauma-informed-work-key-supporting-women

Trevillion, K., Oram, S., Fader, G., & Howard, L. M. (2012). Experiences of Domestic Violence and Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3530507/

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us