Including Online and Telephone Working

Certificate in Clinical Supervision

Become a Skilled, Ethical & Confident Clinical Supervisor with the tools and knowledge to supervise effectively across all platforms.

If you’re interested in becoming a Supervisor, have a look at our Certificate in Clinical Supervision Including Online and Telephone Working.

Become a Skilled, Ethical & Confident Clinical Supervisor with the tools and knowledge to supervise effectively across all platforms.

Supervision is a cornerstone of ethical and effective counselling practice. Whether you’re a seasoned professional or a trainee, understanding the nuances of various supervision models can significantly enhance your therapeutic journey. This guide synthesises insights from key sources to provide a comprehensive overview of supervision’s historical context, diverse models, and practical applications in counselling.

Supervision is vital for professional growth, ethical accountability, and client safety. Over the past few decades, its role in counselling has evolved from informal peer support to structured frameworks. This shift underscores the importance of engaging with supervision that aligns with both the therapist’s and supervisee’s needs. For counsellors, the challenge is navigating the plethora of supervision models to find one that complements their therapeutic approach while meeting professional standards.

Models of Supervision

By the end of this guide, you’ll gain the following actionable insights:

Ken Kelly: This is an area of expertise for you, Rory, and you built our supervision training course and supervision models and understanding those is quite a bit of the course. It’s a bit of the heavy lifting there.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, absolutely, Ken.

I was very fortunate when I was trained because I was trained 24 years ago before we had such rigid curriculums in counsellor training and one of the things that I was taught was supervision as a student.

I was taught supervision. I wasn’t taught to be a supervisor, but I was taught how supervision works. I was taught the model of it.

And it was mightily helpful because when I went to see my supervisor, I had a really good idea of how she worked, and where we may go, where that supervision journey may take us. And it really informed my practice andI was able to look at the material I was going to bring and put it in a way that made the best use of the time we had available.

Ten years went by and I trained as a supervisor, and when I trained as a supervisor, revisited those theories in more depth and got chance to practice them, it again really informed the way that I practiced and it certainly tuned up my self supervisor.

Ken Kelly: Yeah, definitely. And it’s interesting you say that because you’re not alone, Rory. I know when we look at the feedback from our supervision training course, how many say how it’s revolutionised the way that they think about their own delivery of therapy and their preparation for their own supervision.

And I think let’s start off as we often like to do, just with some simple definition. So supervision, the cornerstone of ethical practice, as we know, we’ll work to our ethical frameworks and a supervision model.

It’s a map that guides how supervision works. It’s the under the hood what’s actually happening, and we get so many questions in our Facebook group, from students saying, I’m preparing to go into supervision.

How do I prepare for my first supervision? What should I be taking to my supervisor? And understanding the supervision models gives you much more of a clear understanding of what supervision is there to do, how it supports you, how it supports your client.

And there are different models, and we’re gonna be speaking about the seven eyed model. Rory, you’ll be bringing that today and speaking about what that is and that looks beyond the client counsellor relationship.

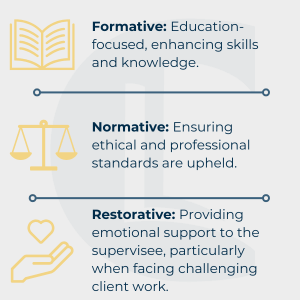

And I’m sure you’ll be speaking about Inskipp and Proctor, the three functions. Learning and standing, or as you love to call them, Rory, the normative, formative, restorative part of a supervision model. Just that normative, formative, restorative understanding of that triangle was revolutionary for me, and I used that information in all of my presentations at supervision, Rory.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, you’re talking about the Inskipp and Proctor model, aren’t you?

That’s very useful as a map to work out exactly where you are coming in. So for those who are not familiar with that model, think of a triangle and along the sides of the triangle, you have got formative, normative and restorative and they’re the doors, if you like, of how you enter supervision.

And here’s the thing, Ken, that’s just one model. I was taught three models of supervision.

And having that in your back pocket as you go through the door is mightily helpful.

Ken Kelly: So helpful. And the next topic area I wanted to go into is why it matters in counselling and psychotherapy.

But just before we go there. Your supervision needs are gonna change as you develop in your practice. As you mature in your practice, you will need very different things from your supervisor when you just graduate or might be in placement to when you’ve been practicing for 10 to 15 years. And Rory, you know that there’s that question of when do I move supervisors?

When does it serve me? There’s a supervision model for that, Rory.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, there is, and that of course is IDM, Integrative Development Model, which is another of the models we teach on our supervision course.

So you get the Inskipp and Proctor model, you get the IDM and IDM is about where you are in your journey. It’s simple as that. It’s sitting down and considering. Where you are and there’s really three positions. There’s apprentice, which is what you are as you come out of your training.

Yes, you’ve done the hours to get your qualification, but that’s really the beginning of your journey and your supervision will reflect that. In fact, you’ll probably find that your supervisor will be the cement between the bricks of the learning you do at college or university.

They will cement that together. And then as you move forward through your practice and you gain more hours of experience you become a journey person.

And you’re on a journey to develop and hone your skill, and hone your knowledge, and tune up your wisdom. And then eventually you become a master crafts person, where the supervision is really about a collaboration between two professionals where you’re sometimes ahead of the supervisor.

There were times in my supervision, I was ahead of my supervisor, and my supervisor would say, I didn’t know about this, Rory, but why don’t you tell me about it and from what you tell me I could then have a conversation with you about how you’re gonna apply it.

It becomes more of a dialogue.

And it’s very different to that of being a student or even someone on that journey. And that’s very useful knowing where you are. And then of course we teach the Shohet and Hawkins, Seven Eyed Model of Supervision, which you are looking through seven different positions to look at how you work with a client, it’s mightily useful. It often informs my practice, Ken.

Ken Kelly: Yes. So moving on to why it matters in counselling what does it do? Having a model gives clarity, shows who holds what responsibility, it reduces defensiveness, increases openness within the relationship, so it serves the relationship as well as the client, as well as you, as the therapist.

And the three jobs of supervision really, it’s keeping you and your client safe, it’s looking at the ethics and the law, it’s keeping you learning, and developing, and moving forward and staying current with your practice, it keeps you watching out for how you are.

Are you seeing too many clients? Are you experiencing burnout? Your supervisor’s not gonna be there to give you therapy, but they are there to support you through those all important aspects of your practice. And I think there’s a lot that we’ve spoken about and it can sound quite confusing.

And that’s why, when your training to become a supervisor, the ethical bodies will recommend you have at least 450 practice hours, or two years of practice experience because there is a lot to hold in a supervision relationship. You’re there for the supervisee, but you are also there for that supervisee’s client.

You are also looking over the relationship, so you have to look in a number of different areas at the same time, and it takes training, it takes dedication, but it takes maturity as well, I think, to be able to be there in service of someone else, Rory.

Rory Lees-Oakes: Yeah, absolutely. And that’s part of that journey person thing, isn’t it?

The 450 hours is where you are not an apprentice anymore, you’re a journey person. You’re journeying towards being a master crafts person.

That’s the key here of service to your supervisee, because we are a profession of service. And as such, as a supervisor, that’s what you are going to be doing. And that service as a supervisor is generated through your experience and your ongoing commitment to the work and CPD which is something that you have to model as a supervisor.

Ken Kelly: It’s a responsibility. Hundred percent. A supervision model is not a heavy academic theory, it’s a tool that is put in place to keep your practice ethical, reflective, and sustainable. We’ve got a handout for this.

And if you’ve listen to this and gone, you know what? I’ve been in practice for more than two years. I think that I’m mature enough, I would love to be a supervisor. Then visit counselling tutor.com, look on our products tab, and you’ll see our supervision training course, you can download the handbook and see if that would be a fit for you.

Supervision in counselling has roots in social work, gaining traction in the 1970s and 1980s through pivotal works by figures such as Joan Mattison, Brigid Proctor, and Patrick Casement. Early approaches, like co-counselling, were informal, but introducing structured models transformed supervision into a disciplined practice. Notably:

Before formal supervision became standardised, ‘co-counselling’ was common, particularly in the Rogerian tradition. Practitioners would meet informally to discuss client work and provide peer-based feedback. Although informal, this model laid the groundwork for today’s structured supervisory practices.

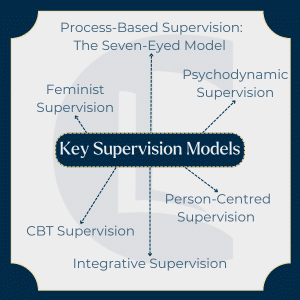

This model emphasises the interplay between personal and societal experiences, grounded in the principle that “the personal is political.” Feminist supervision is particularly effective when working with clients affected by systemic oppression, gender-based violence, or cultural marginalisation. It encourages supervisees and supervisors to reflect on societal power dynamics and their influence on therapeutic relationships.

Anchored in Carl Rogers’ philosophy, this approach encourages a collaborative, non-directive relationship between supervisor and supervisee. While it assumes the supervisee’s competence, it may fall short for trainees needing formative guidance. This model is ideal for practitioners who are aligned with person-centred therapy values.

Drawing on Freud’s theories, psychodynamic supervision explores transference, countertransference, and defence mechanisms. It is structured into three categories:

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy supervision focuses on structured, goal-oriented techniques. Supervisors often assign tasks like reflective homework to ensure alignment with CBT’s evidence-based framework. This model suits supervisees specialising in CBT but mismatches in therapeutic modality can lead to discord.

Integrative supervision is invaluable for eclectic therapists who combine CBT, person-centred, and psychodynamic approaches. Bernard and Goodyear’s Discrimination Model stands out. In this model, the supervisor alternates between roles as a teacher, consultant, and counsellor, depending on the supervisee’s needs.

Models of Supervision

Peter Hawkins and Robin Shohet’s widely adopted model examines supervision through seven interconnected lenses:

This model provides a holistic framework, encouraging reflection across multiple levels of interaction.

Another influential model, Proctor’s Functions of Supervision, highlights three core aspects:

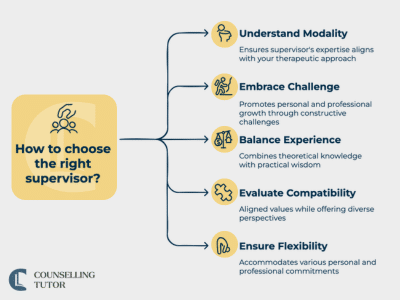

Understanding the modality your supervisor specialises in is critical for productive supervision. For example, a person-centred practitioner may struggle to find value in a CBT-oriented supervisor, as their frameworks and interventions differ fundamentally. Choosing someone whose training aligns with your approach ensures a cohesive and enriching supervisory relationship.

Supervision is a partnership to nurture ethical, competent, and reflective practice. To make the most of this relationship:

Supervisees may encounter challenges during sessions, such as feeling criticised or overwhelmed. It’s essential to reframe these moments as opportunities for growth. Similarly, supervisors may notice parallel processes—when supervisees unconsciously mirror their client’s behaviour—which can be explored to deepen insight and professional understanding.

Look for a supervisor whose training aligns with your therapeutic modality (e.g. CBT, psychodynamic, person‑centred), who brings both challenge and support, and whose style and availability match your growth goals and schedule.

These functions balance learning (formative), professional accountability (normative), and emotional support (restorative) – together ensuring you grow in competence while maintaining client safety and your own resilience.

The Seven‑Eyed Model (Hawkins & Shohet) encourages exploring supervision from multiple lenses – client presentation, therapist’s internal world, relational dynamics, supervisor process, and context. It’s especially helpful when supervision needs to be more reflective, systemic, and depth‑oriented.

Models of Supervision

Supervision is an evolving practice that requires intentionality and alignment with your therapeutic approach. By understanding and selecting from the myriad of supervision models available, you can create a supervisory experience that enriches your practice and ensures the best outcomes for your clients. Remember, supervision is not just a professional requirement—it’s a space for growth, learning, and connection.

Don’t forget the importance of documenting your CPD hours. Keeping a record fulfills ethical and professional requirements, and demonstrates your commitment to growth.

Proctor, B. (1986). Functions of Supervision.

Casement, P. (1985). On Learning from the Patient.

Hawkins, P., & Shohet, R. (1989). Supervision in the Helping Professions.

Feminist Therapy Institute. (1999). Feminist Therapy Guidelines.

Counselling Tutor provides trusted resources for counselling students and qualified practitioners. Our expert-led articles, study guides, and CPD resources are designed to support your growth, confidence, and professional development.

👉 Meet the team behind Counselling Tutor

Notice any broken link or issues with this resource? Kindly let us know by email

Email us