The Core Conditions

The term ‘core conditions’ is often associated with Carl Rogers, but in fact he never actually used the term. Tudor (2000, p. 34) asserts that this term was coined by Carkhuff (1969a, 1969b), who used it in ‘identifying from divergent orientations to therapy “core, facilitative and action-oriented conditions” by which the helper facilitated change in the client (or 'helpee')’.

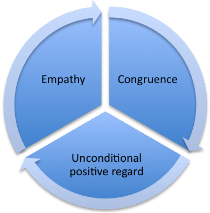

The term ‘core conditions' appears then to have been adopted by people who were close to Rogers, and applied to three of the six necessary and sufficient conditions described by Rogers in 1957: empathy, congruence and unconditional positive regard (UPR). Thus, ‘although Rogers himself did not use the term, it has nevertheless become part of the person-centred lexicon’ (Tudor, 2000, p. 34).

Free Handout Download

The Core Conditions

In the 1957 paper, Rogers identified 6 conditions that he viewed as necessary and sufficient to facilitate change within a client.

Rogers hypothesised that if the client experienced these 'conditions' from the counsellor, a therapeutic relationship would develop and the process of therapeutic change start to begin.

The 3 Core Conditions are:

Empathy

The first condition is called empathy, sometimes referred to as a frame of reference.

The counsellor tries to understand the thoughts and the feelings as the client experiences them, sometimes referred to as ‘walking in someone else’s shoes’.

Try this experiment: with a friend, look at the same object or the view out of the window.

Do you see the same thing?

Probably not.

The reason is that we all have our own perception of the world.

Congruence

The second condition is known as congruence. This means the counsellor is genuine and real.

This condition is important as it allows the client to build a trusting relationship with the counsellor.

The counsellor’s congruence can also help defeat negative attitudes or conditions of worth that others may have placed on the client.

The counsellor’s warm and genuine approach allows the client to feel valued. This in turn builds self-esteem and trust in their own judgement.

Let’s face it, would you want to talk your problems over with someone acting falsely?

No. I thought not.

Unconditional Positive Regard (UPR)

The third condition is known as unconditional positive regard or UPR for short.

Unconditional positive regard allows the client to open up and speak about their difficulties without fear of being criticised or judged.

For a client, it can be a relief to talk about their problems without someone saying, ‘Why did you do this?' or 'Do you think that was a good idea?'

All counsellors – even those who don’t practice person-centred therapy –use the ‘core conditions’ as the base for their practice.

Free Handout Download

The Core Conditions

The Other 3 Conditions in Person Centred Therapy

The 6 Conditions: The 3 Core Conditions and the 3 Hidden Conditions

The first three conditions are empathy, congruence and unconditional positive regard. These first three conditions are called the core conditions, sometimes referred to as the ‘facilitative conditions’ or the ‘therapist's conditions’.

In other words, they are the conditions that the therapist needs to transmit to the client in order for the therapy to work.

The remaining three conditions are sometimes known as the ‘hidden conditions’ or the ‘client's conditions'. These three other conditions are described below.

Condition 4 - Psychological Contact

Psychological contact refers to the therapist and client being "on the same page" psychologically.

If a client is going through a very difficult psychotic episode or is under the influence of medication, street drugs or alcohol, this might make it very difficult for the therapist and client to be in psychological contact.

Condition 5 -The Client's Perception of the Therapist

As well as the therapist transmitting unconditional positive regard and empathy, the client also needs to understand and accept that the therapist is there as a genuine person trying to help them.

The client must accept and feel, at some level, the unconditional positive regard and empathy the therapist is displaying toward them.

Condition 6 - Client Incongruence

Finally, there needs to be client incongruence (i.e. the client has an issue to bring to therapy).

In other words, the client needs to be in some kind of psychological distress.

Rogers pointed out the obvious.

If a client did not have any issues, then therapy would be unlikely to be effective.

For this reason, no one can successfully be sent for therapy. It has to be the client's own choice driven by a difficulty or issue they want to resolve.

How the Core Conditions Facilitate Change

Why are Rogers’ ideas about the six necessary and sufficient conditions so important to facilitate change within the client?

To answer this, we need to turn back to the 1930s and 1940s, when psychoanalysis was the predominant therapy.

Unlike person-centred therapy, psychoanalysis relied on the therapist being a blank slate, distancing themselves from the client, and not getting involved on a personal level.

In other words, the therapist reveals little or nothing of their own personality in therapy. They adopt a veil of expertise and act as the expert.

They even had terms for the two roles in the world of psychoanalysis: ‘analyst’ and ‘analysand’.

Psychoanalysis focused strongly on the past rather than on the here and now.

Rogers challenged this view and decided to find another way of therapy.

Abraham Maslow termed Rogers’ approach humanism, the ‘third force’ in psychology (psychoanalysis being the first, and behaviourism the second).

This humanistic approach was pioneered by Rogers, Maslow, Rollo May and other psychologists.

For humanism to work, the therapist had to be – you’ve guessed it – a human being!

The therapist had to be real, genuine and active in the therapeutic relationship.

Rogers believed that one of the reasons that people struggled in their lives was because they were working to conditions of worth and introjected values.

Individuals were living life on other people’s terms – and were withholding, muting or pushing down their own organismic valuing process. The people they wanted to be, were being pushed away by themselves to please others.

Rogers believed that by using the core conditions of empathy, congruence and unconditional positive regard, the client would feel safe enough to access their own potential.

The client would be able to move towards self-actualisation, as Maslow called it, to be able to find the answers in themselves.

Other Key Concepts of Person Centred Therapy

Free Handout Download

The Core Conditions

- The Seven Stages of Process - How clients start to emotionally grow through the process of therapy.

- The 19 Propositions - Rogers' theory of personality based on the philosophy of Phenomenology.

- Locus of Evaluation - How as humans you sometimes trust others' judgments over your own experience.

- Configurations of Self - A new idea in the Person Centred approach developed by the well-known therapist and writer Dave Mearns.

- Recent Developments in Person Centred Therapy - Such as Fragile Process by Margret Warner

An Ethical Dimension to the Core Conditions

In his book Learning and Being (PCCS Books, 2002 p50), Tony Merry makes the point that there’s an ethical dimension to these core conditions – because they allow the therapist to form a view on whether therapy can take place.

If psychological contact isn’t present, Merry observes:

"...modern developments in person-centred theory have focused on the first condition — that two persons are in psychological contact. Whilst it may seem obvious in counselling (and other) situations, it remains a fact that some clients are unable to form meaningful relationships with counsellors, or can do so only with considerable difficulty. Examples include some people experiencing psychotic episodes, or those in catatonic states."

A Critical View

There are critical voices who are not convinced that counsellors can consistently display the core conditions in the therapy room.

One such detractor is author Jeffrey Masson. He writes in his book Against Therapy (Untreed Reads 2012):

"But if we examine these conditions, we realize that they appear to be genuine only because the circumstances of therapy are artificial. Precisely because the client is seen for only a limited time (less than an hour, once a week), the therapist is (in theory; whether it actually happens is something else again) able to suspend his judgment. In fact, the therapist is not a real person with the client, for if he were, he would have the same reactions he would have with people in his real life, which certainly do not include "unconditional acceptance," lack of judging, or real empathic understanding.

We do not "really accept" everybody we meet. We are constantly judging them, rejecting some, avoiding some (and they us) with good reason. No real person really does any of the things Rogers prescribes in real life. So if the therapist manages to do so in a session, if he appears to be all-accepting and all-understanding, this is merely artifice; it is not reality. I am not saying that such an attitude might not be perceived as helpful by the client, but let us realize that the attitude is no more than playacting. It is the very opposite of what Rogers claims to be the central element in his therapy: genuineness."

Putting It All Together

If the six conditions are present, then – by default, according to Rogers’ theory – therapy will take place.

Over the years, many people have criticised person-centred therapy, asking ‘’How is it possible for a therapist to offer those conditions consistently in the therapy room?"

And to be fair, it can be difficult.

We’re all human beings, and sometimes our ‘volume control’ on the core conditions can turn up and down.

But if it is our genuine intention to offer them, then almost certainly our clients will benefit.

It’s not unusual for people who train in person-centred therapy to take those conditions of empathy, congruence and unconditional positive regard into their own daily lives, using them in their interactions with people other than clients.

While we aim to set our 'volume control to full-on' in the therapy room, we might 'turn it down a little' in everyday life, because not everybody wants therapy – as well as there being many reasons why it’s not a good idea to counsel friends or relatives.

References

Carkhuff, R. R. (1969a). Helping and Human Relations Volume 1: Selection and Training. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Carkhuff, R. R. (1969b). Helping and Human Relations Volume 1: Practice and Research. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Merry, T. (2002). Learning and being in person-centred counselling. Ross-on-Wye: PCCS Books, p.50.

Masson, J. (2012).Against therapy. Untreed Reads, p.P40.

Rogers, C. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, Vol. 21(2), pp.95-103.

Tudor, K. (2000). The Case of the Lost Conditions. Counselling, 33–37.

Pingback: Humanistic Theory: A Person-Centered Approach