Trauma Model Therapy: Essential Insights for Counsellors and Psychotherapists

Trauma Model Therapy (TMT), developed by Colin A. Ross and Naomi Halpern, combines cognitive-behavioural, psychodynamic, and experiential approaches, offering a structured framework for trauma recovery. Though designed within a medical context, its principles are adaptable to various therapeutic settings.

The therapy’s focus on attachment dynamics, locus of control, substance abuse, and the victim-rescuer-perpetrator triangle provides a comprehensive toolset for working with trauma-affected individuals.

This article explores the key components of TMT and its practical applications in psychotherapy, emphasising attachment healing, fostering internal control, and addiction recovery.

Learning Outcomes

- Understand the key goals and components of Trauma Model Therapy.

- Identify the impact of perpetrator attachment and methods for fostering healthier client relationships.

- Apply the locus of control concept to help clients reclaim autonomy.

- Recognise addiction as a response to trauma and how to address it in therapy.

- Navigate the victim-rescuer-perpetrator triangle in therapeutic relationships and avoid collusion with client dynamics.

Main Components of Trauma Model Therapy

Understanding Perpetrator Attachment

A critical aspect of TMT is addressing the client’s attachment to their perpetrator, often manifested as Stockholm Syndrome or trauma bonding. Survivors of trauma can develop attachments to their abusers due to small perceived acts of kindness, leading to complex emotional ties. This can result in a cycle of fear-based attachment, where the client feels a deep connection with their abuser, complicating their recovery.

Implications for Practice: Therapists should recognise and validate these attachments’ nature, helping clients build healthier relationships. The therapeutic relationship becomes a model for a safe and boundaried attachment, guiding the client toward healthier relational patterns. For example, some clients may find healthy interactions with their counsellor novel, particularly those whose past relationships were exploitative or unsafe.

Shifting the Locus of Control

Locus of control, introduced by Julian Rotter, is a critical concept in TMT, particularly for trauma survivors who often believe external forces (e.g. fate, karma, or their abuser’s influence) control their lives. An external locus of control can perpetuate victimisation and disempowerment, while an internal locus promotes self-efficacy and recovery.

Implications for Practice: Counsellors can assist clients in recognising self-limiting beliefs instilled by trauma and external forces. Through therapeutic interventions, clients are encouraged to regain agency, rejecting harmful narratives that perpetuate their victimhood. This shift allows clients to take responsibility for their recovery, fostering resilience and self-empowerment.

Addressing Addiction in Trauma

Self-medication through substance use is a typical response to trauma, where clients turn to drugs or alcohol to alleviate emotional distress. However, addiction can lead to dissociation and further disconnection from recovery processes.

Implications for Practice: Therapists should assess whether a client’s substance use is impeding therapeutic progress. In cases of significant addiction, a dual approach may be necessary, where addiction treatment is pursued in tandem with trauma therapy. It’s crucial to approach this with empathy, recognising that clients may use substances as a coping mechanism. Assisting clients in exploring healthier coping strategies while acknowledging the temporary relief substances provide can facilitate long-term recovery.

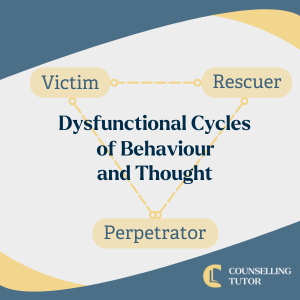

Navigating the Victim-Rescuer-Perpetrator Triangle

The victim-rescuer-perpetrator triangle in TMT, an adaptation of the Karpman Drama Triangle, offers insight into how clients relate to themselves and others. Trauma survivors may oscillate between seeing themselves as victims, perpetrators, or rescuers, trapping them in dysfunctional cycles of behaviour and thought.

Implications for Practice: Practitioners must be aware of this triangle’s impact on the therapeutic relationship, as clients may unconsciously invite the therapist into one of these roles.

By remaining outside these dynamics and helping the client observe their participation in the triangle, you can support the client in breaking these patterns. Regular supervision and reflection on transference and countertransference issues are vital for counsellors to avoid being pulled into these roles.

Final Remarks

Trauma Model Therapy provides a structured yet flexible framework for addressing trauma’s profound effects on individuals. By understanding and integrating its core components—perpetrator attachment, locus of control shifts, substance use management, and the victim-rescuer-perpetrator triangle—therapists can help clients move toward recovery and autonomy.

The therapeutic relationship becomes crucial, modelling healthy attachment and empowering clients to reclaim control over their lives. For practitioners, navigating these dynamics requires self-awareness, supervision, and a commitment to trauma-informed practice.

References and Further Reading

Clarkson, P. (2003). The Therapeutic Relationship. Whurr Publishers.

Karpman, S. (1968). Fairy tales and script drama analysis. Transactional Analysis Bulletin, 7(26), 39-43.

Ross, C. A., & Halpern, N. (2009). Trauma Model Therapy: A Treatment Approach for Trauma, Dissociation and Complex Comorbidity. Manitou Communications.